When Siblings Become Teachers: It’s Not Just Parents Who Find Themselves Thrust Into the Demanding Role of At-Home Educators

By Zoë Kirsch | April 10, 2020

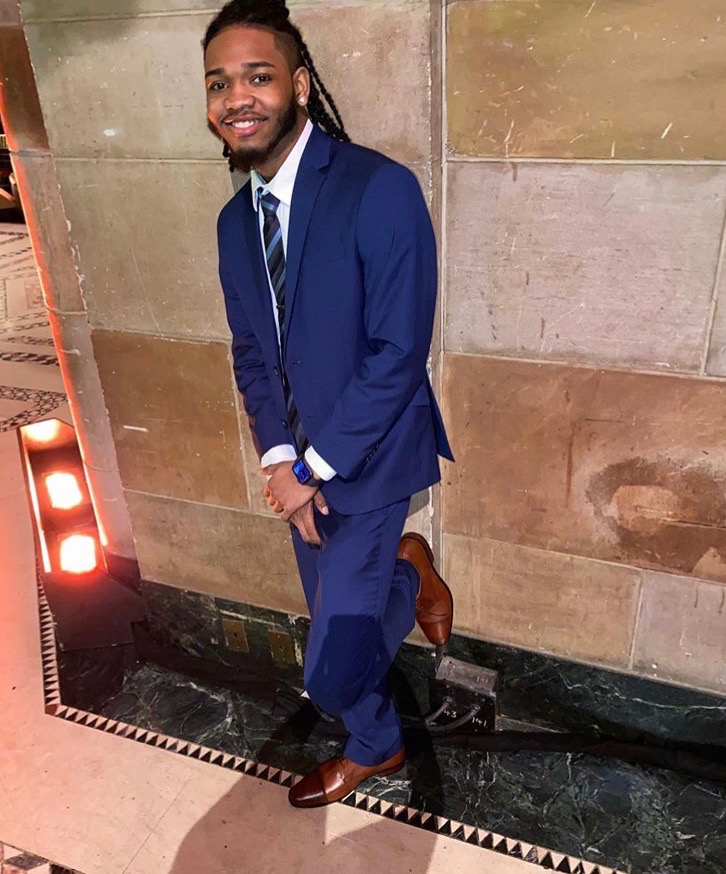

When 22-year-old Lillian Acosta learned that New York City schools would close due to the coronavirus, she suddenly felt a strange kinship with the parents among her co-workers.

Acosta, who has been working her ed tech job remotely from her family’s home in Queens since the pandemic hit, took notes as her colleagues asked each other for tutor referrals and tips for getting their children through lessons.

Acosta doesn’t have any kids of her own. She was gathering information on behalf of somebody else: her 14-year-old brother, who has an Individualized Education Program for his special needs and has been struggling with the transition to online learning.

“A lot of people are dealing with their children,” she says. “For me, it’s Edward.”

While she doesn’t personally know anyone in her situation, Lillian Acosta isn’t alone. School closures due to the coronavirus have left thousands of young New Yorkers saddled with an enormous new responsibility: leading their siblings through online learning at home.

The burden has been felt most acutely by youth in low-income communities of color whose workload has suddenly grown from afterschool care for younger brothers and sisters to all-day homeschooling. Some already counted corresponding with teachers and translating for family among their responsibilities when the coronavirus took hold. Their parents tend to work long hours; if they’re immigrants, they’re less likely to be comfortable speaking English and more likely to rely on their older children to navigate the American school system.

Many of these young people are simultaneously juggling competing duties, such as earning enough money to put food on the table. Still in school themselves or just barely out of it, they spend their days coaching, cajoling and advocating on their siblings’ behalf — ultimately sacrificing hours of their own time to help others learn. Remote education isn’t just a heavy lift for parents, it turns out — it’s a strain for older siblings, too.

Data on education-related sibling caregiving is scarce; it’s only within the past decade that researchers have started looking at the issue in its own right, and many studies have used small sample sizes. The most recently available data on the issue show that, as of 2005, there were around 1.4 million kids and teens tending to someone in their family — with about 11 percent of those young people in charge of a sibling.

Each morning, Acosta settles into her spot at the coffee table in her family’s living room, about 10 feet away from her brother, whose books are spread across the dining room table. Their mother, who in safer times works as a housekeeper, cooks and cleans their home and occasionally FaceTimes with family in Brazil.

The transition to online learning has been particularly challenging for Edward, a freshman at the 1,600-student Richmond Hill High School who likes math and making TikTok videos and reads at a third-grade level. In school, he receives speech therapy and reading help. Although he’s been in touch with his guidance counselor and gotten extra reading support once a week online, it wasn’t until two weeks into homeschooling that someone contacted him about restarting his speech therapy.

“Remote learning requires a lot of independence,” explains Maggie Moroff, special education policy coordinator at Advocates for Children of New York, a nonprofit working on behalf of marginalized students. “By definition, if you get special ed services, it means you need more support above and beyond your peers.”

Acosta says that Edward’s distance learning curriculum doesn’t provide him with enough structure. “He hates it,” she says. “It’s a really big adjustment.”

To compensate for what the online learning lacks, she’s come up with a system. Each morning around 9, Acosta reviews her brother’s slides on Google Classroom and reaches out to the reading tutor whom she found independently online and pays $90 a day out of pocket. She emails him Edward’s materials for English and social studies, while Edward gets started on his math and science assignments. From 2 until 4 in the afternoon, Edward’s tutor guides him through his reading. At 7:30 in the evening, Edward wraps up, and Lillian reviews his work and helps him submit it online. He touches base throughout the day if he has questions, too — if, for instance, the iPad that he’s using isn’t working, or if he can’t solve a math problem. Getting Edward through his school day takes Acosta two hours on a good day, five hours on a bad one.

This sort of sacrifice is all too familiar to Melisa Cabascango, a 17-year-old attending the Bushwick Campus of the Brooklyn School for Social Justice.

The past month has been tumultuous for the high school senior. First, the pandemic left her mother, a street vendor, unable to sell homemade Ecuadorian crafts. Then, the restaurant where Cabascango had been working as a pasta chef cut her hours. A day later, it closed for good. Cabascango’s family was left without any income for the month. They wondered how they’d pay for rent, utilities and food.

The other day, Cabascango found herself growing frustrated with a biology assignment — not because its content was prohibitively difficult but because she wasn’t able to tune in to her teacher’s office hours. She was hamstrung from seeking help by the schedule that she and her brother had built around sharing the single laptop they had to complete their assignments. Cabascango had requested another device from the city’s Department of Education but hadn’t heard back from anyone yet.

When New York City schools closed, Melisa’s mother had taken her aside and told her that, while she knew her daughter had her own education to manage, she should also do her best to help her younger brother, Mike, who has an IEP plan and is in the eighth grade at Intermediate School 77 in Queens.

Melisa rose to the occasion, drawing up a schedule that would give each sibling their best shot at finishing their work. She motivated Mike to meet his deadlines and cheered him on when he grew discouraged with his math and science assignments. On average, helping her brother with his schoolwork takes two to three hours a day.

“We don’t know how long this will last,” says Melisa. “I don’t want him to fall back and not be able to graduate [middle school] on time.”

She’s right to be concerned: Mayor Bill de Blasio has said that the coronavirus could keep New York City public schools, the nation’s largest school district, with 1.1 million students, closed for the rest of the academic year.

Andrea Flores is an assistant professor at Brown University writing a book on education-related “sibcare” — activities encompassing everything from looking out for a younger sibling to providing full-time child care. The research for her book started in 2012, when she spent time with young Latina women in Nashville, tracing the guiding influence they had upon their younger siblings’ educations.

While Flores hasn’t explicitly studied the impact of the coronavirus, she says that she’s sure the switch to online learning is being felt deeply by that same population.

“Schools moving to online platforms is something that would disproportionately affect poor minority young people,” she says. “I imagine for some of these students, we’ll see what I saw five years ago, which is that they’re making cuts to their own education in support of their younger siblings.”

“I try to wake up early enough to check up on the little things. I don’t try to be overbearing because I’m not a parent, but I have to make sure they’re up to par on the things they’re doing.” —Sarshevack Mnahsheh, 20, who is helping homeschool his five younger siblings during the coronavirus shutdown

For the large Mnahsheh family in the Bronx, siblings teaching one another has, thus far, been the key to making it through the rest of the school year.

Every day, 20-year-old Sarshevack Mnahsheh, a 2017 graduate of the Urban Assembly School for Applied Math and Science and the eldest brother living at home, gets up and checks in with his five younger siblings to make sure they’re prepared to finish their schoolwork on time. (Sar has two additional siblings, but 19-year-old Tael isn’t in school anymore and 23-year-old Nahsi has moved out.)

“I try to wake up early enough to check up on the little things,” says Sar. “I don’t try to be overbearing because I’m not a parent, but I have to make sure they’re up to par on the things they’re doing.”

Later, Sar’s mother will return from her job as an administrator at Harlem Hospital Center, and Sar will head to his job at Key Food, where he’ll work into the night stocking shelves, slicing meat behind the deli counter and manning the cash register. His girlfriend, meanwhile, provides backup in the family’s makeshift classroom between dialing COVID patients to give them their results from PWNHealth, a national diagnostic testing network.

Sar clusters his siblings strategically so that they can give each other extra support: 15-year-old Elianna is paired with 13-year-old Gmaryah, and 10-year-old Josiah goes with 6-year-old Aamir.

“It can be challenging,” says Sar. “They have to adjust to not being in school. Usually, they have a teacher, who can explain something to them more in-depth. When it’s online, you may get it when the teacher’s talking to you, but then you may forget.” He says his siblings have to work extra hard to remember the lessons when they do their homework.

Flores, the Brown University professor, says teachers should remain mindful of the pressures that students like Melisa face at home, especially now in light of the pandemic. “A lot of times, these sacrifices that older siblings make go unacknowledged by their schools,” she says. “It can be hard to have that work be visible, especially if the [younger] students are in different schools.”

To avoid that work being rendered invisible, administrators and teachers should thoughtfully take stock of their student body and its needs, Flores says. “When young people are guiding their siblings’ education, they’re not just learners but also caretakers,” she explains. “They’re a full person who needs to be supported in a social-emotional way.”

Flores recommends that teachers adapt to the current moment by providing what she calls “asynchronous” learning opportunities, meaning that students are given what they need to finish their work on their own schedules. That will reduce the likelihood that timing, along with a lack of technological resources, thwarts their efforts to learn, as Melisa experienced with her biology assignment. Teachers can assign online quizzes without requiring that students sign on at a particular time, for example, or they can hold both afternoon and evening office hours, rather than having just one block of time during the day.

Although educators are trying not to buckle under their own set of enormous pressures, like doing their best to keep students from falling behind, Flores says, they should take a moment to consider what they can learn from young people like Lillian, Melisa and Sar. After all, research has shown that caring for younger siblings can have an upside, instilling youth with self-reliance, resilience and a sense of responsibility.

On a recent rainy afternoon, Edward Acosta stood up from the dining room table and slammed down his iPad.

“It’s too hard,” he said. “I don’t get it.”

Lillian looked at her brother, then at her laptop, then at her brother again. Her own work could wait. She took a seat next to him. “Let’s calm down,” she said. “What’s happening here?”

She drew the iPad toward her and read the algebra problem, which involved factoring trinomials. She thought for a minute, remembering her high school classroom, her math teacher and the useful tricks that he had taught her. One of them had been about the constants in each set of parentheses adding up to equal the middle one …

Jackpot. “Oh,” said Lillian. “I know how this goes.”

Lead image: Lillian and Edward Acosta at Lillian’s commencement party celebrating her graduation from Baruch College last June. (Lillian Acosta)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter