What’s It Really Like Attending a Truly Innovative High School? 4 Students Give a Firsthand Look

This piece first appeared on the EWA blog

Amida Nigena very nearly quit the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design before the first semester of her freshman year had ended. It was 2015, the school was brand-new, and it wasn’t anything like other campuses in the Denver school system.

The district’s goal in creating the school was to educate a generation of innovators, graduates who had mastered the self-direction skills that would get them through college and help them flourish in the workforce.

Like most American high school students, Nigena had years of experience navigating classes where everyone did the same thing at more or less the same pace. But as a member of the Denver School of Innovation’s inaugural class of 100 ninth-graders, suddenly she was in charge of not just getting her work done, but figuring out what that work would be.

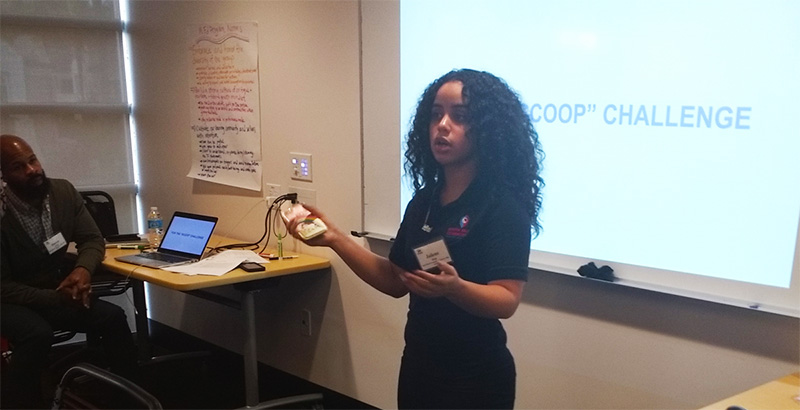

“I hated the school,” Nigena recently confessed, recounting her experience for a group of journalists at an Education Writers of America seminar on high school redesign. “The first year was really rough on everyone. We were just thrown in. We didn’t know what personalized learning was, and neither did our teachers.”

The school’s principal, Lisa Simms, agreed.

“We hired 10 teachers who were rock stars in a traditional setting,” she said at the seminar. But the school’s approach was so new that the staff had to start with basics like establishing a common vocabulary.

“At the start, it was hard to even find a definition of competence,” Simms said. “What does it mean to be competent? How do you show mastery?”

Figuring out what personalized learning is, and whether it stands a chance of living up to its attendant buzz, was front and center at the December seminar, titled “A Reporter’s Guide to Rethinking the American High School.”

Because, by definition, personalization takes different forms in different schools, hearing about the school days of students attending four “break-the-mold” high schools was a high point of the gathering.

The seminar took place at San Diego’s High Tech High, a pioneer among a small but growing cadre of schools where everything from letter grades to “seat time” is up for reinvention. A public charter school network, High Tech High operates 13 campuses at the elementary and secondary levels, with an emphasis on hands-on, project-based learning.

Journalists in attendance heard from Nigena and several other students:

- Jailene Diaz, who attends South Bronx Community Charter High School in New York;

- Odalis Ramirez, a student at Vista Challenge High School, located just north of San Diego in the Vista Unified School District; and

- Ethan Traugh, who attends Iowa BIG High School in Cedar Rapids.

Vista and Iowa BIG both received grants from XQ: The Super Schools Project, an effort to focus attention on high school redesign associated with the Emerson Collective, an organization launched by Laurene Powell Jobs, widow of Steve Jobs. Vista will get $10 million over the course of five years; BIG will get $1 million.

Nigena’s school has also received philanthropic support as one of 10 schools opened in the 2014–15 and 2015–16 school years with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York through its Opportunity By Design initiative. (Carnegie provided major funding for the EWA seminar on high school redesign.)

South Bronx Community Charter High School is an outgrowth of former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Young Men’s Initiative.

Iowa BIG is a partnership among the Cedar Rapids, College Community, and Linn-Mar school districts, and is located in southeastern Iowa’s so-called Creative Corridor. Businesses, civic leaders, and community members submit proposed projects for students to work on, which the school reviews and, if accepted, turns into in-depth learning experiences that take students out into the community.

Traugh’s parents wanted him to play football, he said during the student panel, a dream he didn’t entirely embrace. After talking to his economics teacher about the sport’s “opportunity cost” — staying put in his local high school instead of pursuing his own interests — Traugh concluded he was being held captive by it.

“I just really needed some juice in my life,” he said. “Some passion. Like a lot of kids, I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

He heard about BIG from a friend. Now, he attends early-morning gym class and four other periods at his local “normal school” before leaving at 11 a.m. — sometimes for Iowa BIG and sometimes not.

“I look at the tasks I have laid out for myself and my team and decide where to go,” Traugh explained. “Thursday I had some emails to write, so I went home and did that and did some research into photosynthesis.”

Afterward, he went to BIG to work on a hydroponic planter.

Like the other students who spoke at the seminar, Traugh identified the real-world relevance of the projects he works on as the reason he is so engaged.

“I fall asleep in my Advanced Placement computer science class in my traditional school,” he said. “It’s my easiest class but my lowest grade. I blow off the homework.”

Like Traugh, Diaz heard about her school — which occupies one floor at Boricua College — from a friend. Like Nigena, she initially felt adrift.

“What made me stay was the setting,” Diaz said, as she joked, “It’s in a college, so I thought, OK, I’m grown now.”

South Bronx Community’s students also complete projects and must demonstrate competence in the subjects addressed. In addition to a focus on social justice and race equity, the school emphasizes well-being and development of strong student identities.

“I’m never alone when I’m doing my work,” Diaz said, naming a teacher she feels particularly close to. “I open up to her because she always says, ‘You remind me of myself when I was younger.’ ”

Close relationships with teachers are motivating for Ramirez, too. Her school, Vista, has 660 ninth-graders, but because they are grouped in six “houses” with teams of teachers who collaborate across academic disciplines, it feels like a small school, she said.

“Students need to work together as a team, and we need to work with our teachers as a team,” Ramirez said.

All four schools are being watched closely, both for innovations that could help other schools address academic achievement gaps and for challenges in implementation.

The Opportunity By Design schools’ progress is being closely tracked by the RAND Corp. In addition, RAND is gathering research on innovative schools launched as part of a separate foundation-backed initiative, the Next Generation Learning Challenge.

Journalists at the seminar also heard from researchers tracking the initiatives and other innovative high schools for RAND and Digital Promise, an independent nonprofit created by Congress to examine the potential roles technology can play in school innovation.

Despite a rocky start at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, Nigena ultimately decided to stay.

“I talked to the principal,” she explained. “He sat down and asked why I didn’t like school and what would make it better. It really improved the second semester.”

She’s on track to graduate next year with at least 15 college credits and a deep well of self-confidence instilled, she said, by the process of driving her own high school experience.

“It’s taught me to be patient and to persevere, and also that it’s OK to fail,” Nigena said. “That process has really changed me, especially when things don’t go exactly well.”

She added: “You definitely have to be able to do things by yourself.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)