What Schools Should Do About COVID’s Chronic Impact on Special Ed Students

Cunningham: The challenges facing special education are deep-rooted, nuanced and long term. Similar solutions are needed to address them

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

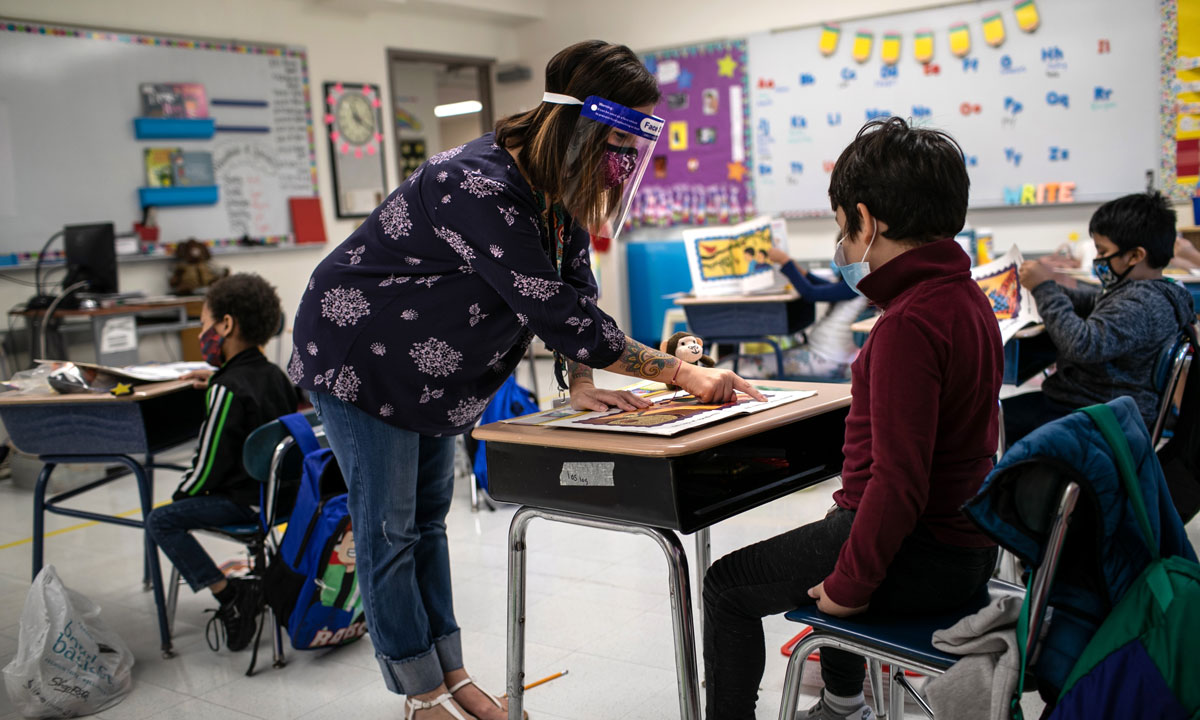

Over the past few years, schools have rallied to ease the impact of students’ disrupted academic learning and the broad social, physical, emotional and psychological implications of the pandemic. Districts knew that making slight adjustments wouldn’t cut it, as they were up against some of the biggest learning challenges ever presented. Educators were empowered to rely on technology and reimagine their classrooms through creative and innovative teaching approaches aimed at connecting with students and their strengths.

Many districts witnessed how effective the supports traditionally included under special education services — like providing more one-on-one help and assistance with organizing schoolwork — were for all students.

But in expanding this assistance, districts did not provide additional supports and services to students who need special education — and it shows. The National Center for Education Statistics reported that students with disabilities on average scored 32 points lower in math and 40 points lower in reading than students without disabilities. The Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates found that only 18% of students with disabilities had been offered compensatory services through 2021.

It was not difficult to predict that the intersection of the pandemic and the challenges presented by disabilities would amplify the impact of interrupted learning on these students. And now, it should not be hard to envision what will happen to neurodivergent students once neurotypical students begin to more quickly fill in the learning gaps caused by the pandemic.

For students with learning and thinking differences who need special education, the impact of COVID-19 will be chronic even though it feels as though the crisis has passed. It’s never been more urgent for schools to stop focusing on teaching to the middle and, instead, concentrate on the kids with disabilities who consistently get pushed to the bottom. Here’s where schools can start:

First, they should focus on approaches that benefit all learners. Students struggle for different reasons, but implementing response to intervention and multi-tiered systems of support ensures that educators can provide proper academic instruction, as well as social-emotional support, to all kids before they fall behind. Additionally, embracing Universal Design for Learning as a core principle of school culture and a necessary aspect of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives can demonstrate how all students can recover academically and gain confidence at a similar rate. The goal is to use a variety of teaching methods to remove barriers to learning so all students have the same opportunities to succeed.

Decades of research have proven that these tactics positively impact students with special education needs, from offering different assessment formats, like presentations and posters, to delivering information visually, orally and tactically to address various learning preferences. They also benefit all students. Why wouldn’t they be prioritized in every classroom?

Second, districts must use Individualized Education Program and 504 Plans to prioritize the most critical issues for a student. They are also effective as tools for advocating for more compensatory services regardless of school or district policies.

It’s not just special education teachers who need access to these plans — they empower all teachers to make decisions about students’ particular learning and support needs based on their strengths, growth areas and challenges. While the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 require just one general education teacher to participate in the IEP process, districts must commit to ensuring IEP/504 discussions gather and relay the input and feedback of all teachers. That’s the only way for all the caregivers in a student’s life to work toward the same goals and missions.

Lastly, the education community needs to focus on what must happen at the systems level for large-scale transformations to occur. First, districts must extend special education services to students beyond the age of 21, to help those deeply affected by interrupted learning address the existing chronic issue. Various states have started to implement this change in an effort to address the lack of post-high school transition services. When that happens, districts should also offer counseling about the impact of staying in high school — how students can take advantage of the additional time and resources offered to them, as well as how they can navigate the social impact of staying in school longer.

At a state and federal levels, there need to be specific reporting requirements around COVID funds and compensatory services to ensure money is allocated to the right places to create real impact for students with disabilities.

To address the chronic issues of teacher burnout and shortages — especially in special education — districts must also consider alternative pathways to certifications and professional development. The traditional four-year-degree-to-classroom pipeline is no longer sufficient. Schools can look to employ professionals leaving the corporate world and create pathways for aides and assistants that don’t require them to spend additional money on education.

At the end of the day, the challenges facing special education are deep-rooted, nuanced and long term. Similar solutions are needed to address them and ensure kids with learning and thinking differences aren’t forgotten altogether.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)