What Netflix’s ‘Adolescence’ Gets Wrong — and Right — About ‘Kids These Days’

Roehlkepartain: The majority of students feel supported by their families and other adults and safe at school. We shouldn’t accept a deficit mindset.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

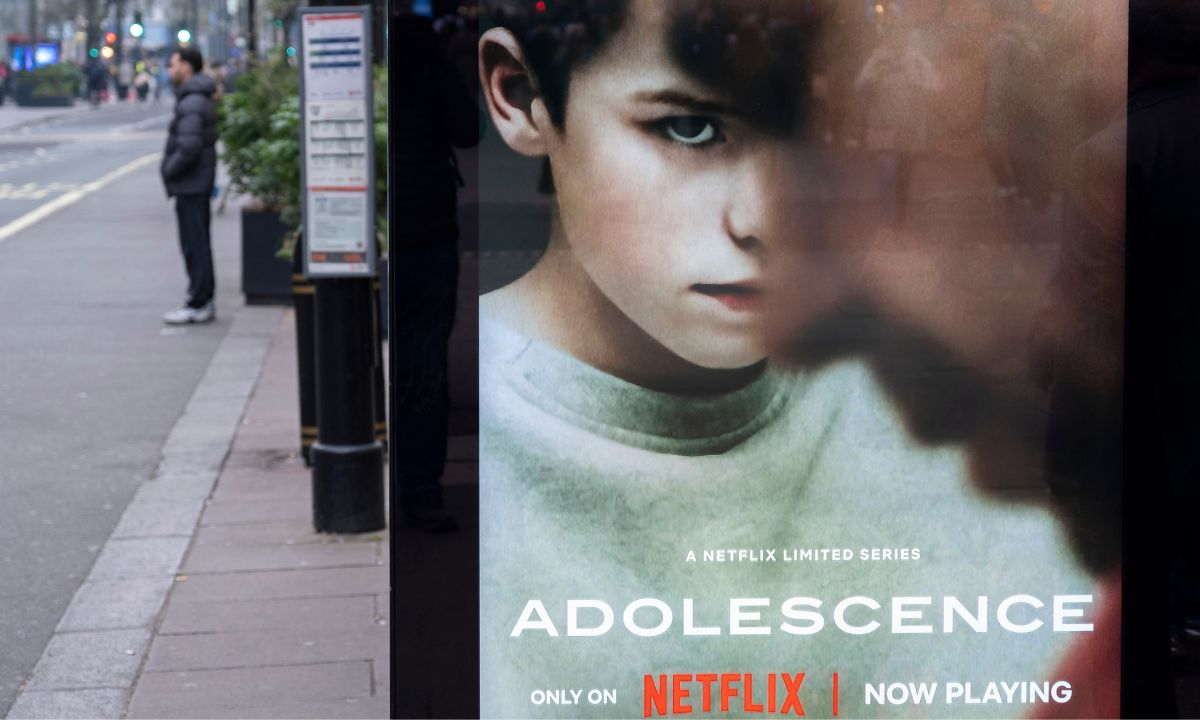

I finished watching Netflix’s series, Adolescence. It revolves around 13-year-old Jamie Miller, who just killed Katie Leonard, a girl from his school. It’s a gripping story, brilliantly produced. Everyone I know has been telling everyone else that they have to watch it, particularly if they have teenagers. My kids are older, but I was curious, especially because my day job involves researching youth development.

By the end, though, I wish it had been called An Adolescent.

I’m sure its title was intentional. My alternative isn’t catchy and theirs resonates with parent’s and society’s deep fears and default mindsets about terrifying teens. These include:

- Our kids, especially boys, are on the edge of falling into the dangerous trap of social media.

- They are unruly and often clash with detached, emotional dads.

- They lack respect for adults and struggle in chaotic schools where teachers resort to shouting to maintain control.

Many discussions about youth in TV shows, movies, research, and everyday conversations tend to focus on negative issues and problems, despite social science suggesting a more positive approach. Cultural narratives about “kids these days” often focus on deficits, especially regarding youth from groups that have been the targets of discrimination and oppression. They are among the most maligned, creating harmful stereotypes that leave many feeling undervalued.

Ages 10 to 25 are crucial for the development of youth and young adults — for their identity formation, decision-making, and personal growth, and also to learn from mistakes. While some young people do get caught up in dangerous content online, the vast majority don’t. While some do struggle, their experiences should not define or overshadow the dynamic potential of this developmental stage like Adolescence does.

Many of the poignant moments in Adolescence are between boys and their dads. These scenes show both generations struggling awkwardly to connect, to understand each other, and to express affection. The series’ co-creator and co-writer, Stephen Graham, says that Jamie’s father, Eddie Miller, isn’t “overly tender and doesn’t tell his boy he loves him constantly…. [But he] brings in as much love as he can. He does to the best of his ability.” As viewers, it seems just fine, since that’s just the way it is.

The myth of the inevitable conflict between teenagers and parents, though persistent, is overblown. Relationships between parents and teens change, and everyday bickering is normal as young people become more independent. But only 5% to 15% of teenagers have serious, ongoing conflicts with their parents. Perceptions of the level of conflict vary between mothers, fathers, and teenagers within the same family, and they change over time. None of that means that families are a war zone or that teens live in a different world from their parents.

Our research consistently shows that, on average, teenagers from all backgrounds view their families positively. In a study of over 27,000 young people grades 4 to 12, the vast majority said they have strong relationships with their parents, with 85% reporting that their families consistently provide love and support. It’s not okay that 14% of these youth say their family gives them love and support only sometimes or not at all. Those families need targeted support and healing. But they are not the norm that you might assume by what is portrayed in Adolescence and public discourse.

Teenagers and adults inhabit separate worlds in Adolescence. Teenagers use a secret language of emojis that adults struggle to understand, leading to communication breakdowns and frustration. Psychologist Briony Ariston works hard to build rapport with Jamie, so much so that he asks her if she likes him “just as a person.” It’s evident she has developed a bond with him when she breaks down after he leaves, though she doesn’t show him.

Jamie’s deepest longing is to know that despite committing a terrible act, he has inherent value as a person and he is loved. Mutual relationships are essential for building trust, but some people who work with youth have conflated the importance of maintaining professional boundaries with not expressing responsible, genuine care. This is essential for effective practice and for recognizing the humanity of even those who have committed crimes.

Leaders in juvenile justice reform argue the justice system would be more effective if those in the system could be seen as, in Jamie’s words, “just as a person” while they are serving their sentence. Unfortunately, youth of color and others who have been marginalized are less likely to be liked “just as a person” when the adults around them are mainly from the majority culture.

About 75% of young people report feeling supported by adults outside their families. While surveys indicate variability in support from specific groups like teachers or youth workers, adults generally view their relationships with youth more positively than the youth themselves do. This highlights the opportunity for improvement, showing that current realities differ from common perceptions about adolescence.

Finally, Adolescence portrayed secondary schools as hellholes where teachers scream at students in a futile effort to gain a modicum of control. Yes, U.S. teachers report that verbal threats and violent behaviors have increased since before the pandemic. Yet despite facing challenges, our research found 68% of students grades 4 to 12 often feel safe at school, and 67% believe rules are enforced fairly.

Creating safer, relationship-centered schools requires significant effort. Many students, teachers, and families are bullied or overlooked, especially in lower-resourced communities that struggle to meet daily needs. However, across diverse schools, administrators, educators, and families are collaborating to foster respectful and engaging environments where every student feels welcomed and safe. It’s challenging, but it is achievable.

Adolescence is a compelling series that raises questions about families, adolescence, youth culture, and society, which merits far more attention than they usually get. I worry that the vast majority of compelling stories that shape our culture’s thoughts about kids reinforce narrow, problematic, and deficit-focused views. I want to hear diverse stories of teens from various places, cultures, and backgrounds, showcasing their sparks, struggles, and solutions. I seek narratives of young people, with the support of adults, becoming positive forces in their communities and the world as they transition into adulthood.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)