What If Every Struggling Student Had a Tutor? It Won’t Be Cheap, but It Might Be Worth It

Instead, teachers’ jobs can be incredibly challenging, and low-performing students can stay trapped at the bottom.

“Imagine being a teacher in a classroom that has 25, 30, even 35 kids, and some of the kids are at a ninth-grade or 10th-grade math level, and other kids are a fourth- or fifth-grade math level,” said Jonathan Guryan, a professor at Northwestern University. “From the standpoint of a teacher trying to teach kids who are at such different levels of math knowledge — it just makes the job of being a classroom teacher very difficult.”

Guryan has a solution to this problem that has vexed educators forever: His research suggests that providing one tutor to every two struggling students might be more economically viable than it would seem, and would lead to large gains in student test scores and course grades. It would still cost districts a large chunk of money, but it could well pay off for students.

When researchers Will Dobbie and Roland Fryer examined New York City charter schools, they found five practices that were correlated with student achievement gains. One was what they described as “high-dosage” tutoring, with small groups of six or fewer students per tutor.

Then, Fryer, in a remarkable experiment, exported these practices to schools in Houston and found that they led to notable gains in math, though not reading. Tutoring specifically seemed to make a difference. Students in grades in which tutoring was offered, particularly those in middle and high school, made larger gains than students in grades in which tutoring was not implemented but other aspects of the charter “best practices” were. The initiative was not cheap, particularly the tutoring aspect, but Fryer argues that the policy is more cost-effective than traditional class-size reductions or pre-K expansion.

More recent research also suggests that intensive tutoring is part of the secret sauce of successful charters. The paper finds that when comparing charters to the traditional public schools in the same area, the one factor predicting higher performance among charters is high-dosage tutoring.

But can such tutoring be successfully exported to traditional public schools? Yes, according to a rigorous study conducted in Chicago involving nearly 3,000 students.

The team of researchers, including Fryer and Guryan, studied a program that paired two 10th-grade boys whose math test scores were low with a tutor who provided remediation help during a regular class period in the school day. The tutoring was integrated with the students’ regular math class, and there were frequent tests to gauge progress. (The program, oddly, was limited to male students. The researchers say this is because their test scores and graduation rates are significantly lower than girls’.)

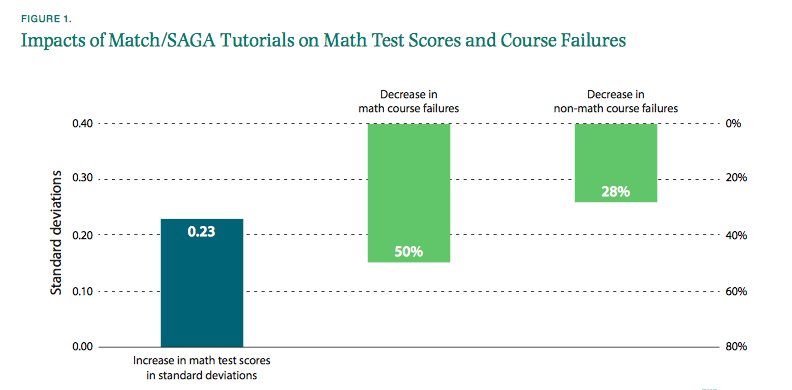

The findings were remarkable, particularly considering how often much-hyped education initiatives produce disappointing results. Students who received tutoring saw big jumps in their math test scores on multiple exams and were much less likely to fail regular math courses. The average student started at the 34th percentile of student performance and, after tutoring, jumped to the 42nd percentile. Tutored students were even less likely to flunk non-math classes.

“Part of the reason you sense such excitement in my voice when I talk about these results,” said Guryan in an interview, “is how surprising it is to find something that has such strong effects, especially for kids who are in high school.”

The initiative was extremely costly: $3,800 per participating student. For context, Chicago spends about $12,000 per pupil in total. But the researchers say it’s a big bang even for many bucks: “The impacts per dollar spent appear to be at least as large as almost any other educational intervention that has been rigorously tested.”

That’s still a lot of money, though less than it might be. Tutoring can be thought of as a drastic class-size reduction, meaning hiring more teachers, which is always costly.

The way the Chicago and Houston programs made the price (kind of) reasonable was by using a model from Match, a charter school network in Boston. Specifically, tutors were largely recent college graduates, given relatively minimal training (100 hours’ worth), and paid just $17,000 and benefits over nine months, similar to City Year and Americorps service programs.

The hardest, but most important, part of any education reform shown to be effective in one setting is determining whether and how it can be implemented elsewhere. A March 2016 paper for the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution — co-authored by Guryan as well as Roseanna Ander and Jens Ludwig of the University of Chicago — recommends expanding intensive tutoring like in the Chicago model to schools nationally.

“We envision the possibility that school districts around the country might have tutorials integrated into the regular school day on a wide scale,” the report states. Under their plan, high-poverty public schools that receive Title I federal dollars would use that money to provide tutorials to students struggling in math in third through 10th grades.

The chief impediment is the money, which the report says could be reduced to $2,500 per tutored student if implemented more broadly.

But even if schools had the money, could intensive tutoring be scaled successfully?

It’s one thing to recruit a handful of poorly paid but eager tutors necessary for a small program; it’s quite another to get the tens of thousands of tutors necessary to expand the initiative. It could also be harder to recruit tutors in rural areas.

The Hamilton paper estimates that 140,000 instructors would need to be hired to provide two-to-one instruction for struggling third- through 10th-graders in the nation’s 100 largest school districts.

Not only might it be hard to find all these new tutors, but they might not be as effective as the tutors who were part of the small programs. This is a classic problem when districts make traditional reductions in kids per class. When California slashed class sizes and went on a hiring spree, the new teachers were much less qualified, which diluted the positive effects of smaller classes.

Guryan acknowledges that this is a concern: “It’s a question of whether [schools] would be able to find tutors who would be as effective when they’re trying to hire five times as many or 10 times as many or more.”

He said he’s currently researching this issue.

The Hamilton report notes that where it’s been implemented, there were many more potential tutors applying than available spots, implying that there is “at least some room to grow.”

Districts could also experiment with ways to reduce costs or expand the program more slowly. Maybe tutoring should be three or four students per instructor. Perhaps it should be targeted only to high school students or those who are truly at the very bottom in math performance.

But the biggest hurdle remains the dollars and cents. The Hamilton authors recommend simply repurposing federal Title I money — but that means taking dollars from elsewhere. Maybe the resources are better spent on tutoring, but the cuts necessary would likely be painful and substantial. According to the latest data, states are currently spending less on education than prior to the Great Recession.

Guryan said he’s not sure where he’d cut. “School districts have very difficult choices to make, given the budgets that they have,” he said. “What [the results of the tutoring program] tell me is that there are ways to allocate some of the funding that’s [now] going to the status quo toward this program and improve student learning outcomes.”

Moreover, Guryan notes, “There’s no law that says per-pupil [spending] has to be $10,000 or $11,000 per kid — it could be increased.”

In fact, some high-profile charter networks, like KIPP and Uncommon Schools in New York City, spend substantially more money than similar public schools through sizable private donations. Simply implementing charter “best practices” — like intensive tutoring — may be difficult if one of those approaches involves spending a lot more money.

In other words, intensive tutoring might provide big benefits to struggling students, but it can’t work if policymakers can’t find the money to pay for it.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)