It’s recess time at Manitou School in Cold Spring, N.Y., and the sun is shining through a large jungle gym. But the fifth- and sixth-graders couldn’t be less interested in the playground — or their break from the classroom. Students sit on the swing set bent over spiral notebooks, writing about building castles in medieval England or piloting a World War II fighter jet.

The students and their teacher, Christi O’Donnell, are participating in National Novel Writing Month for the first time. Begun in 1999, NaNoWriMo, as it is commonly known, taps the creativity of budding authors by signing them up to start a 50,000-word novel during the month of November. Last year, nearly half a million people participated, including 80,000 K-12 students and teachers who took part in the Young Writers Program.

Writing 50,000 words is a tall order for anyone, particularly for kids, so most students set their own goals. O’Donnell’s students aim for 7,000 to 12,000 words and get a head start from the Young Writers Program, which includes a Common Core–aligned curriculum. The program spans three months, allowing time to pre-craft characters, develop story arcs — and even hone math skills in calculating how many words must be written per day to attain the final goal.

It’s a marathon of a writing assignment, but teachers report high levels of engagement as students learn not only about creative writing but also about motivation and grit.

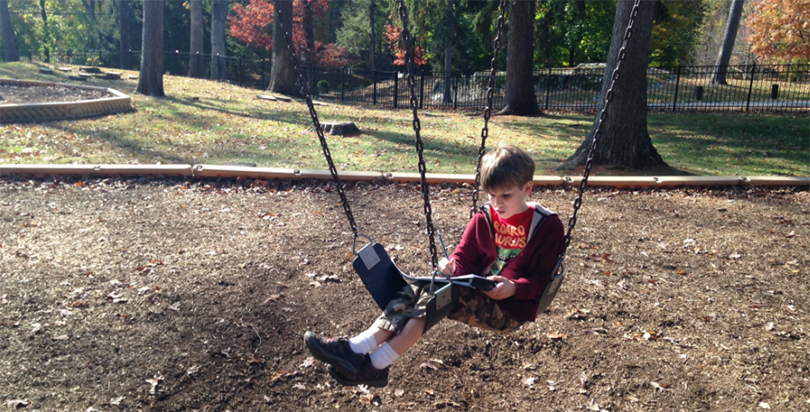

A boy sits on a swing, trying to conjure his novel outside the Manitou School.

Photo: Courtesy The Manitou School

Most students have never embarked on any writing challenge like this, yet the motivation is high, O’Donnell reported. Her students spend a half-hour every day writing; parents say they have to chide their children about writing at the dinner table.

“Students who are not generally motivated are most motivated by this because they feel they can really put their own ideas and voice into it,” O’Donnell said. In fact, she said, after just 30 minutes of drafting a novel, her most reluctant writer told her that a sequel was already in the works.

Several of O’Donnell’s students described for The 74 what motivates them to skip recess for extra writing time.

“I think of my setting and characters, and I want to make something happen,” said Max Del Monte, age 11. His story, called “The Young Hero,” is about a teenage boy named John who is a Spitfire pilot fighting the Nazis during World War II.

Ten-year-old Fia Stein-Marrison said her interest in her sci-fi story, called “The Blue Moon of Lorkipia,” is her motivation. “Sometimes you get to a part where you don’t know what happens next,” she said. “It’s sort of like reading a book, but you get to decide which direction it goes in, and sometimes it can get really suspenseful.” In her story, a group of friends discover a dwarf named Dwarn who has has come to warn the people of Lorkipia about a vengeful blue devil named Varon the Villain.

One criticism of NaNoWriMo is that quality of writing may be sacrificed for quantity — and teachers agreed that during November, simply getting ideas onto paper is the goal. To help her students focus on judgment-free writing, O’Donnell had them draw pictures of their inner editors and literally locked them in the school’s machine room. In December, the students will set the “editors” free as they revise their own stories and their peers’.

Manitou School students voluntarily spend their recess writing novels.

Photo: Courtesy The Manitou School

At Coventry Village School in Vermont, Dawn Walls-Thumma, who teaches fifth through eighth grades, runs NaNoWriMo as an after-school program once a week. She makes the students hot chocolate, tea and snacks —because that’s what every real writer needs, she tells them — and the students talk through story ideas before they begin writing.

Like O’Donnell, Walls-Thumma said she was surprised at how motivated her 22 students were to write novels outside school, without any grade or prize attached. A three-time NaNoWriMo “winner” herself, she told her students that simply attaining the goal of writing 50,000 words was its own reward. The kids, she said, have taken that idea and run with it, setting their own personal word-count goals and poking their heads into her classroom during daily study hall to ask if they can work on their novels with her.

Walls-Thumma credited the school with fostering an environment that values students’ creativity and initiative. “We emphasize persistence, and not success or failure,” she said. “The number of students willing to give that a go speaks to the fact that the school creates that culture.”

The ability to tell their stories, whether through memoir, fan fiction or fantasy, is important for her students in the rural Vermont town near the Canadian border. Many come from disadvantaged communities and don’t have computers or internet access at home where they can write, Walls-Thumma said.

Even after NaNoWriMo concludes, she said, she hopes students will be interested in continuing in an after-school writing club. An avid writer herself, Walls-Thumma said she’s always seen a need for creative writing as an extracurricular activity.

For older students participating in NaNoWriMo, the word “grit” is heard more often than “motivation.” Sophomores in teacher Matt Morone’s English classes at Pascack Valley High School in Hillsdale, N.J., have the option of completing the full 50,000-word challenge for credit toward their narrative-writing standards. About 70 students are participating, pounding out at least 1,667 words per day to meet their goal.

“Most took the challenge of NaNoWriMo not to fulfill the requirements of the class but to have that challenge and that reward,” said student Shauna McLean, who added that most of the students in her honors English class enjoy proving themselves by tackling difficult assignments.

“Today was the ‘dark night of the soul’ speech,” Morone said on the Monday following the first weekend of NaNoWriMo. While some students had camped out at Starbucks and completed the more than 3,000 words necessary to stay on target, others didn’t add a word to their stories. Clearly, a pep talk was needed.

For Morone, a goal is to instill perseverance and grit as life skills that his students can take with them when they leave his class at year’s end. Over the summer, he assigned optional reading: Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, by Angela Duckworth. He comes back to these themes as his students encounter challenging assignments. So when it comes to NaNoWriMo, Morone will be giving credit based not on the quality of the writing but on its completion.

“This isn’t about me. This is about them conquering the mountain,” he said.

That mountain for many students is realizing they can do something they might have thought only professional adults could accomplish. “They build it up so much in their head: ‘[Novel writing], that’s something someone else does,’ ” Morone said. “It’s not; it’s something someone who sits down and writes a book does.”

And through National Novel Writing Month, students are slowly discovering the power of fiction and grit, one word at a time.

McLean, for example, is writing about a girl who discovers she has magic powers and uses them to make the world a better place. What are these magic powers? “She doesn’t know,” McLean said. “And I don’t either.”

At least, not yet.

;)