‘We’re All Kings’: Inside the All-Boys High School That’s Leading D.C.’s Campaign to Help Young Men of Color

Washington, D.C.

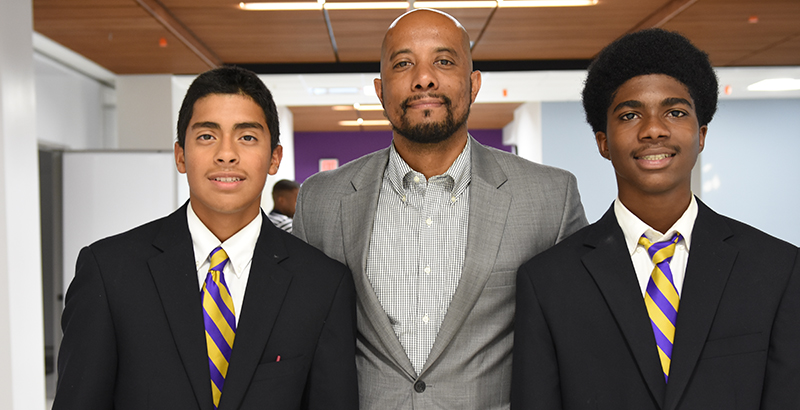

The students, a few dozen ninth-grade boys, are sharply dressed in the prep-school classics: khaki pants, purple- and yellow-striped ties and navy blue blazers, though by now, eight days before the end of the school year, there’s rips in more than a few of the elbows.

On a muggy day in early June, they had already slugged through spitting rain and Metro train delays to get to the Ron Brown College Prep High School, a building still in the midst of renovations. In the far reaches of D.C.’s northeastern quadrant, the school sits just a few blocks from the street that marks the city’s Maryland border.

Ron Brown College Prep High School, whose inaugural freshman class became sophomores when school reopened Aug. 21, is perhaps the most visible, and controversial, part of a $20 million initiative to support young men of color launched in 2015 by former Chancellor Kaya Henderson and Mayor Muriel Bowser.

On that humid June day, the still-freshman class began the morning like every other, with a community circle. Most start with “shout-outs” that see the boys offering praise for peers or faculty, but today they are quiet, so the leader has them debate social issues instead. They discuss things like whether there are more African-American men enrolled in college or incarcerated, and whether young men of color do better long-term when raised by two parents than by one.

This community circle is used for both practical and pedagogical reasons: to give a time buffer so transit delays and responsibilities like getting siblings to school mean less missed class time, and to place an emphasis on social-emotional learning.

“We want our young men to have a space where they can actually respect each other and provide positive feedback to each other and receive praise from their peers, receive praise from adults, to get used to actually giving and receiving that, which is far too few and far between for young men of their age,” Principal Benjamin Williams said.

No girls allowed

The boys have come around to the idea of no female classmates, Williams said.

Paul Gray transferred to Ron Brown from Wilson, an 1,800-student high school on the opposite end of the city, and the small class sizes and close attention from teachers have helped his grades improve.

“It’s a challenge, but also helped me focus,” Gray said of the lack of female classmates.

That said, the young kings of Ron Brown, as the staff call them, are still 15-year-old boys.

On a spring trip to the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum, they tried to pick up girls from another school at the butterfly exhibit, Zavian Morgan said.

Morgan, Gray, and two other classmates took a break from an English class assignment on Shakespeare to talk about their school and debate the seemingly essential detail of whether said girls were from Maryland or D.C. What wasn’t up for debate, the boys said, was that the interest was mutual.

The lack of girls has certainly attracted the attention of adult advocates.

The ACLU of the District of Columbia has questioned the legality of the program, saying the $20 million undertaking violates Title IX, which bans discrimination in education based on sex. The group said in a report that the school should be open to girls. Federal regulations issued in 2015 allow single-sex public schools so long as there is a comparable option for students of the other gender or “if such action constitutes remedial or affirmative action.”

There is no DCPS school just for girls, though there is one all-girls pre-K-8 charter school. There are, of course, plenty of private single-sex options in the city, including the Washington Jesuit Academy, which serves low-income middle school boys of color in an extended day and year program.

The D.C. Opportunity Scholarship, the only federally funded voucher program, also serves about 1,200 low-income students in D.C., providing up to $12,981 for private high school tuition, including single-sex options.

Ron Brown’s focus on boys only was necessary for a group of students being left behind even as results improved across the district, Henderson told NPR in August last year. Black and Hispanic boys in D.C. have the lowest proficiency rates on most standardized tests and the lowest high school graduation rates of any group.

“If we’re going to get different results from our young men, we have to try different strategies, and this is one that we think is well worth it,” she said.

Staff and students know about the legal concerns, but are leaving the worrying up to district officials, Williams said.

“We’ll let DCPS and their fine lawyers take care of that, and I’m only responsible for what’s happening in this building, and I’ll continue to work to be responsible for that,” he said.

Overcoming stereotypes

The number of single-sex schools aimed at specifically helping children of color has proliferated in recent years, without much research to back up why, said Joseph Nelson, an assistant professor at Swarthmore College.

He helped with a 2010 study of all-boys high schools in New York, Chicago, Houston, and Atlanta that found the most important qualities for success at single-sex schools were the same as at any other — excellent teachers, strong leadership, parental involvement, and the like.

“My stance on single-sex or coeducational education is there should be a good school first and then the composition of its students are other factors that you consider in constructing a learning environment,” he said.

https://www.facebook.com/RBHSMonarchs/videos/1848830575376874/

Adults at Ron Brown aim to empower the students, like using a monarch, represented as a lion — essential in a society that frequently stereotypes young men of color.

Many schools struggle with helping boys figure out what they need to do to break away from negative societal expectations and be successful students, Nelson said.

“That message is so thick and so prominent that it requires almost a daily effort within the school to disrupt it,” he said.

At Ron Brown, one answer to that has been highlighting accomplished men of color.

The building, its first floor freshly refurbished, with the rest set for year two, previously housed a neighborhood middle school, also called Ron Brown. Brown was the first African-American head of a political party and President Bill Clinton’s first commerce secretary. He was killed at age 54, one of 35 people who died in a 1996 plane crash during a trade mission to the former Yugoslavia.

The inaugural class is split into 10 councils that compete over grades and attendance. Each council, which Williams equates to the four houses in the Harry Potter series, is named after a famous man of color, such as Barack Obama, Cesar Chavez, Frederick Douglass, and Thurgood Marshall.

Getting results

Standardized test results for Ron Brown for its freshman-only 2016–17 school year aren’t available. (D.C.’s standardized tests look at 10th grade English and geometry, which students also usually take their sophomore year.) But there have been big social-emotional gains for the school’s 105 freshmen, Williams said. Nearly all of them, 96 percent, are black, and 44 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a measure of poverty in schools. Most live in Wards 7 and 8, those east of the Anacostia River, home to many of the poorest and highest-crime neighborhoods in the city.

“I think they’ve internalized this mission and they’re excited about being able to change their own narrative and to write their own narrative,” the principal said. “You can see that in their faces on a daily basis.”

Williams, who previously was assistant principal at The School Without Walls, a magnet school, said the Ron Brown students have made years of progress in just eight months.

The boys have really embraced the idea of praising others, taking responsibility for actions and figuring out how to overcome challenges, and, more important, going to college, he said.

Tremayne Warren has his eye on a big college prize: Oxford University in England.

His mom was the real force behind him coming, he said, but he’s grown to like the school’s college tours and trips, extracurricular activities, and supportive atmosphere.

“We’re all a family here,” Warren said. “We’re all monarchs. We’re all kings.”

Early projections were that 85 percent of the inaugural class would re-enroll for next year, a number Williams expects will hit 95 percent.

Ron Brown’s gleaming new building has opened its doors to a new class, many of them the middle school friends of the boys who are now sophomores.

There are more than 40 future young kings, freshmen and sophomores, on the school’s waiting list.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)