‘We are Becoming Grayer’: New Hampshire’s Shrinking Birth Rates and Shuttered Schools Offer Preview for the Nation

By Kevin Mahnken | June 22, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

After more than a century, the end came swiftly for Hallsville Elementary School.

The smallest school in Manchester, New Hampshire, enrolling around 260 children from kindergarten to fifth grade, is also the oldest continually operating facility in the school district. First opened in 1891, it now requires millions of dollars in renovations and, like several schools across the city, is under-enrolled. In December, a consulting group studying Manchester’s school capacity and utilization recommended shuttering four elementary schools as a way of cutting costs and operating more efficiently. A few months later, the local board approved just one for closure: Hallsville.

“It was a proposal in the middle of the school year, and then, next thing you know, it was happening,” said Tina Krajewski, who has sent two children to Hallsville. “Looking back at it, it’s just insane to know that it’s going to be gone. It breaks my heart.”

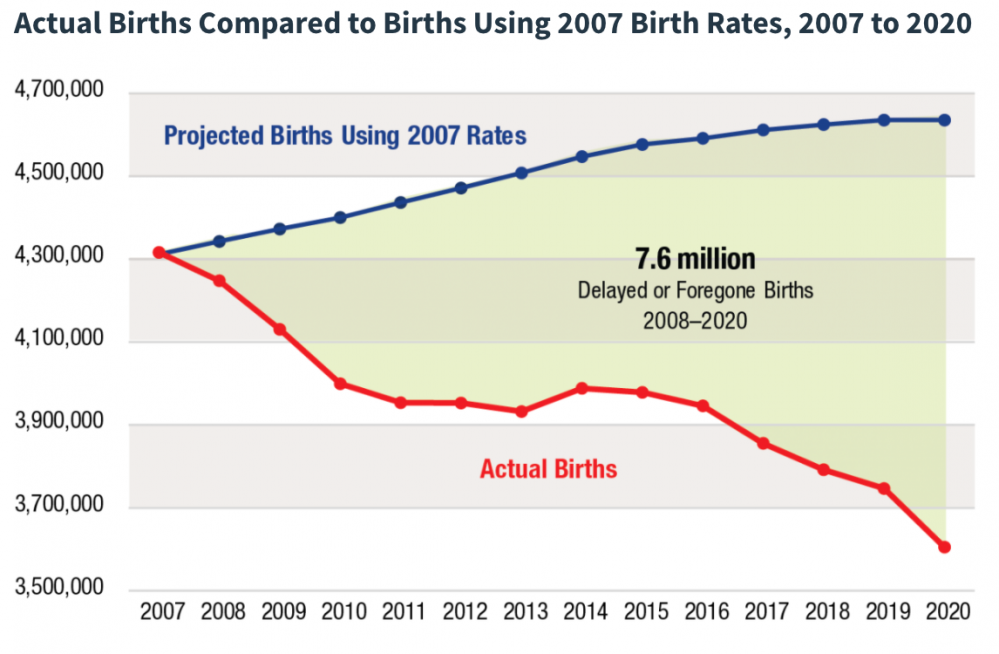

Long before the emergence of COVID-19, schools around the United States were experiencing an erosion in their enrollment numbers. Our nationwide K-12 enrollment, roughly 55 million kids, remains one of the largest in the world. But birth rates have slipped ever since the Great Recession, first abruptly, then persistently. When the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released new data on population growth in May, few experts were surprised to see that total births had fallen to their lowest number since 1979. Over 700,000 fewer babies were born in 2020 than in 2007, the year the financial crisis began, even though there are now significantly more women in their child-bearing years.

Fertility rates vary significantly by state, from the comparative peaks in the Dakotas to the aged and declining population in Vermont. New Hampshire, with 48.2 births per 1,000 women aged 15-44, ranks above only its Green Mountain neighbor in general fertility. If not for the impressive influx of migrants from other states, drawn equally by its natural beauty and high quality of life, New Hampshire’s population would also be shrinking. And fewer children means fewer students; Manchester, the state’s economic capital and largest school district by far, has lost more than one-fifth of its enrollment over the last decade.

With no rebound in sight — the pandemic has clearly suppressed family formation — what’s already happened there may well be coming to a school near you.

The nationwide slowdown in natural population growth isn’t limited to a few regions or segments of society. Though researchers have noted a trend in recent years of births decreasing among younger women and rising somewhat for their older counterparts, fertility sank this year for all age ranges between 15 and 44 (including record lows for those between ages 20 and 29). Women in all racial and ethnic categories are having fewer children, but recent years have brought especially plunging rates for Hispanic women, who previously made up for much of the collapse among other groups. And while states with the very lowest growth are clustered largely in the West and Northeast, the “birth dearth” has now spread to every area of the country.

In New England, the nation’s hardest-hit region, local leaders increasingly feel the need to respond. The adjustment is leading Manchester to consider moves that will go much further than closing a single elementary school. At a special school board meeting last month, Superintendent John Goldhardt unveiled a plan to merge the district’s three traditional high schools into one new building. Originally hired two years ago from Utah, one of the fastest-growing parts of the country, Goldhardt said in an interview that the city’s shifting demographics meant that urgent action was required.

“We are becoming grayer,” he said. “I’m new to the state, but a lot of our high school and college graduates don’t stay, so the population as a whole is older. I’m not sure what is causing that, but I know that birth rates and family sizes are way down.”

Krajewski said she was waiting to hear more about the consolidation plan, and that she understands the challenge of maintaining aging facilities with fewer students. But that doesn’t take the sting out of losing a school where her father was a student decades ago, and where her niece now attends as a fifth-grader. As the academic year winds down, she is busy assembling the building’s 130 years of institutional memory into one last yearbook.

“It’s really emotional for me because this is the final yearbook that Hallsville will ever have,” she said. “And I’m grateful to be the one to help put it together for the students, but at the same time, it’s like, ‘This is gone.”

The Great Recession’s long hangover

The United States has historically been a kind of demographic unicorn, enjoying both world-leading levels of education and economic development while also posting year after year of comparatively high population growth. Even as international competitors like Europe and Japan had to cope with ever-worsening ratios of retirees to prime-age workers, America’s big families and relatively welcoming posture toward immigration made us the exception.

The long hangover of the Great Recession changed all that. Policymakers initially saw the drop in births beginning in 2008 as typical of a contractionary economy and likely to recover once catastrophic joblessness and uncertainty dissipated. But even a decade later, as the pre-pandemic labor market neared full employment, fertility continued to dwindle. All told, according to the calculations of demographer Kenneth Johnson, nearly 8 million fewer babies have been born over the last 13 years than would have arrived if 2007-era birth rates had continued.

Johnson, a professor at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy, said that the question in recent years has been whether those missing births were either delayed — by younger women who decided to start families later in life — or foregone entirely. Even before the pandemic, he noticed that fertility among older women, while steady, was not compensating for the lower numbers earlier in the decade; in its wake, he added, even fewer births are likely to follow.

“If you think about it, the women who delayed their births in their early 20s, who are now in their early 30s, may well have been planning to have babies about now,” Johnson said. “But the latest data I’ve seen [suggests] that one-third of women were planning to delay births because of COVID. If that’s the case, we’ve got another delay on top of the ones we’ve already seen.”

New Hampshire is a case in point: This year, it was one of 25 states that saw more deaths than births (13,511 vs. 11,773). That might not come as a total surprise in a year when COVID killed hundreds of thousands, but in New Hampshire, the trend actually dates back to 2017. The softening in growth, most apparent in the rural precincts near the Canadian border, is also felt downstate, where transplants from Massachusetts and other New England states have often fled in search of more favorable tax rates.

Formerly an industrial capital that housed some of the biggest textile and shoe manufacturers in the world, Manchester is now in the process of reinventing itself as a “Silicon Millyard.” Its 112,000 residents make up the largest urban center in northern New England, but between 2007 and 2017, annual births in the city fell over 14 percent, from 1,664 to 1,423. At the same time, home prices throughout New Hampshire were rising even before the pandemic-era run on real estate, in large measure due to more retirees choosing to “age in place,” which prevents housing supply from turning over.

Krajewski, whose parents each came from families of nine or more children, argued that the climbing cost of childcare and prevalence of one-parent households have led more young people to have fewer children, or even abstain from parenthood altogether.

“It’s a very different dynamic than what it used to be when my dad went to elementary school, where the classes were bigger and there were more kids in general,” she said. “It’s not like that now. A lot of my friends only have one or two children; some of my friends don’t have any children and don’t want children.”

Peter Lubelczyk is the principal of Jewett Street Elementary School, which will be receiving the bulk of students displaced from Hallsville this fall. A former Jewett student himself, he pointed to the lack of young families as a key explanation for Manchester’s enrollment shortfalls.

“The neighborhood where I grew up, 50 or 60 percent of the neighbors are still there who were there when I was a kid,” Lubelczyk said. “My mother is still living in the house I was raised in, where she’s been for 50 years. I think there are a lot of families who stay in their homes for a long time because it’s their forever home. That older population in Manchester will definitely result in declining school populations.”

Families ‘feeling the crunch’

It would be one thing if decreasing birth cohorts simply meant smaller class sizes. But it’s not that simple: Every student lost to districts like Manchester also translates into fewer education dollars sent from legislators in Concord.

A major outlier in the northeast, New Hampshire has always been characterized by skepticism toward government. With no state taxes on wages or sales, it raises less revenue than its neighbors and ranks bottom in the country for per-pupil education aid dispensed by the state. According to a 2020 brief from the New England Public Policy Center (a think tank affiliated with the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston), an average of 47 percent of K-12 education revenue in the 2015-16 school year came from state governments. In Vermont, the figure was much higher, 89 percent. In New Hampshire, just 33 percent of funding came from the state, with 61 percent coming from local taxpayers.

Bruce Mallory, a professor emeritus of education at UNH’s Carsey School and observer of New Hampshire schools for decades, has recently worked with a public commission studying education finance in the state. He said that the intense reliance on local revenues can make communities particularly sensitive to fluctuations in population size.

“A new housing development goes up in a small community, 50 new kids, and that puts huge strains on the school budget,” Mallory observed. “The reverse of that is, school populations decline, taxpayers ask, ‘How come our local education costs are staying flat or going up when the enrollment is down? We’re not going to pay for that!’’

In an attempt to gain relief, Manchester voters approved a cap on both property tax revenues and expenditures in 2009. That restriction can be overridden, and periodically has been to secure more money for schools. But between the smaller pot of funding and the relatively higher needs of local students — the district enrolls far more English learners and low-income pupils than is typical in New Hampshire, one of the highest-income states in the country — budgets are stretched thin. One cost model, commissioned last year from the American Institutes for Research by the state panel studying education finance, estimated that Manchester schools were underfunded by “almost $10,000 per student.”

Nicole Leapley was elected to the local school board in 2019. This May, she co-signed an open letter petitioning for reforms to the state’s funding policies, and in an interview, described the status quo as “anti-young-people.”

“The whole playing field is set up in a way that really doesn’t support families,” she said. “If our population is growing, it’s mostly people saying, ‘Oh, I’d like to retire to the seacoast.’ But I think families are feeling the crunch and probably are being driven away.”

One of the most significant signs of strain is the state of the district’s building stock. According to the capacity review released last year, Manchester schools currently face $158 million in deferred maintenance and capital improvement costs — the result of buildings like Hallsville, which have been in use long after their typical lifecycle was spent. Superintendent Goldhardt said that the price tag for renovation could be much greater than the cost of building new schools.

“Some may say, ‘I’m okay with this old, shabby building that we’re paying a lot of money for, and that we’re going to have to pour millions into,’” he said. “But eventually, it’s like the old car: You can only replace the radiator so many times before the bottom falls out, and you can’t drive it anymore because the floor’s rusted out. The same thing happens to school buildings.”

That realization is part of what’s driving the push to combine the district’s three traditional high schools into one newly built structure (a fourth, a career and vocational school, would be moved to one of the vacated buildings). The proposal is also a concession to numbers: Not only are the existing high schools aging, they also collectively enroll 1,500 fewer students than they have capacity for. Board members warmly received the plan — which also includes converting all middle schools into magnet programs and introducing a French language immersion system at one of the city’s remaining elementary schools — at a public Zoom meeting convened in May. But if enacted, it would be the biggest shakeup Manchester schools have seen in decades.

In an email, Mallory said the steps being considered were “indications of the stress that all [New Hampshire] districts are under.” If the status quo is maintained, he added, other areas “will also be closing or consolidating buildings in addition to cutting back staff and reducing supports for students most in need. That is, the budget and education program situation for such schools will only get worse.”

In the meantime, Hallsville elementary will end operations fairly quickly. Kym Prive, a parent who has sent three children to the school, said that even families without students currently enrolled have been saddened by the move to close a neighborhood institution. More poignant still is the fact that students lost most of the school’s last year to remote classes necessitated by COVID.

“We want to make it memorable for them, which is hard. Even looking at the yearbook, there aren’t as many pictures from this year of them in school. We’re hoping to be able to still do a good end-of-year send-off for everyone, since it’ll be the end of Hallsville altogether.”

Lead art by The 74’s Meghan Gallagher (Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter