Want to Teach in Hawaii? They’re Hiring — and Probably Recruiting in a City Near You

EDlection 2016 is The 74’s ongoing coverage of state-level education news, issues and leaders in the run up to 2016 elections. (Among our previous stories in this series, stories from Mississippi, Nevada, Ohio, Wyoming and Texas. See the latest stories here).

When constant teacher turnover is added to this mix — about 10 percent of teachers switch schools, move away or leave the profession each year, according to one report — students’ already fragile emotional and academic well-being is further strained, Hauge said in an interview. The veteran educator attended Wai’anae schools as a student, taught chemistry for 10 years and worked as an administrator in the district for 20 years.

“It doesn’t build stability in the schools and it engenders a feeling of rejection in the students,” she said. “It’s totally unintended because they’re great people, but (it’s hard) when they come in and fly back to the mainland after a couple of years.”

Hawaii’s teacher shortage isn’t new, but state officials are pouring more resources than usual this year into the state’s nationwide recruiting program to fill as many as 1,600 expected vacancies for the 2016-17 school year, said Barbara Krieg, assistant superintendent for human resources in the Hawaii Department of Education.

This spring, recruiters traveled between Dallas, Los Angeles, Portland, Newark and Chicago to talk to teacher candidates about jobs on the islands.

At the same time, at least one school is piloting a grow-your-own approach to encourage Hawaii’s own students to pursue a teaching track.

(More: Why Oklahoma is racing to put nearly 1,000 uncertified teachers in its classrooms)

The state doesn’t generate enough homegrown educators — only about one-third of its vacancies are filled with teachers coming out of Hawaii’s own teacher preparation programs, while the remainder are staffed with transplants or natives who left Hawaii and decided to return, Krieg said.

“The fact remains that our state-based teacher education programs literally don’t graduate nearly enough teachers to fill our needs,” Krieg said. “We hope that by reaching out on the mainland, we are also offering an opportunity to future or existing teachers who have ties here and want to come home.”

Turnover among the teaching staff of 13,100 has risen in recent years, too, with 352 teachers retiring last school year, Krieg said, up from 300 four years earlier. When it comes to new teachers, roughly 50 percent leave their district within their first five years of employment, the Honolulu Civil Beat reported in 2013.

Hauge, the principal in Wai’anae, believes that recruiting educators from the mainland — especially from programs like Teach for America, which sends recent college graduates to teach for two years in some of the country’s neediest schools, including in Hawaii — is “simply a stop-gap measure.” While many of them are well-qualified, only about 20 percent of teachers from the mainland stay permanently, she estimated.

Hawaii students score lower than the U.S. average on math, science, reading and writing tests, making it all the more unfair that struggling students there lack a permanent supply of experienced, dedicated teachers, school officials said.

Fed up with this years-long cycle, Hauge and her staff finally decided, “What the heck, we’re going to grow our own teachers,” she said.

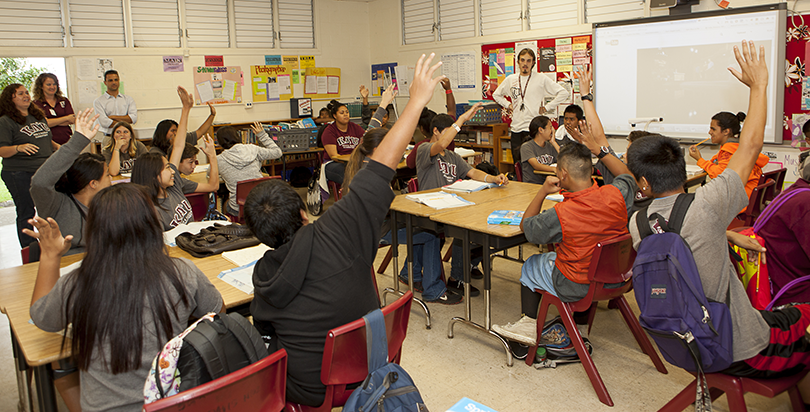

Last fall the school launched a “teaching pathway” as part of its existing Career and Technical Education program. About 50 students are participating; Hauge said she expects to double that number within a couple of years.

The two-year program for high school juniors and seniors includes college coursework in early childhood development, at local schools and online. Students also participate in internships at local elementary and high schools.

“It’s really exciting to hear kids say they want to come back as math teachers,” Hauge said.

The program is the first of its kind in Hawaii that she is aware of, Hauge said.

It isn’t a cure-all, she acknowledges, and the efforts to recruit and retain top teachers will continue.

“We hope that they will come back as K-12 teachers in our school system, but even if they don’t, they’ve really gained valuable skills that will help them in the workplace … like how to work with all kinds of people,” she said.

Hawaii is not alone in its struggle to attract sufficient numbers — and types — of teachers to its public schools. States including California, Nevada and Oklahoma have stretched to fill positions in 2015 and 2016 for different reasons.

(More: Desperate Times Call for Urgent School Reforms in Nevada)

Math, along with science and special education, are the most-needed subject areas and often the hardest to fill.

“We’re not the only ones facing teacher shortages … but what exacerbates the situation for Hawaii is, of course, our geographic uniqueness,” Krieg, the state education official, said. “We don’t have the ability to attract people from just across the border.”

The average starting salary for a teacher in Hawaii hovers around $45,100, among the highest in the states, but the cost of living in paradise is also very high. That detracts from the seemingly easy sell to candidates weary of Northeast winters, officials and educators say.

“Hawaii has one of the highest teacher turnover rates in the nation and this is more so for people that come from the mainland," Corey Rosenlee, president of the Hawaii State Teachers Association, told Fox News 11 in Honolulu. "They say, 'I can't live here' and they leave and we have to go back and recruit, and this cycle just continually happens."

Marist College in Poughkeepsie has been a strong feeder school, and this year the department saw a lot of interest from Dallas, Krieg said.

One area superintendent traveled to South Dakota and Nebraska in an effort to find teacher candidates who were accustomed to small-town life and therefore more likely to be comfortable settling into a distant island environment.

“Matching expectations” is how Principal Elton Kinoshita refers to the recruiting strategy.

Kinoshita’s schools serve 570 students on Lanai, which has about 3,000 residents. The shortages in his schools were so bad in 2014-15 that he spent the first two months of the school year teaching math while scrambling to fulfill his principal duties after classes, at night and on weekends, the Honolulu Civil beat reported.

The situation has improved some since then, but the schools still struggle to find enough substitute teachers to cover absences and illnesses, Kinoshita told The 74.

New hires arriving from the mainland will often enroll in a master’s degree program and complete their teaching certification while working full-time at his school, Kinoshita said.

Hawaii allows individuals with bachelor’s degrees to teach while earning their license under its emergency certification statues. As of December, the state had made about 205 of these emergency hires of teachers without any license, Krieg said.

Altogether during the first half of the 2015-16 school year, she said, the state processed 1,088 new teacher hires and 386 of them didn’t have a Hawaii license. Of those without a state license, 96 had a license from elsewhere and were on track to complete the Hawaii license process, while 87 were Teach for America-trained educators.

On Lanai, about 10 teachers of his current staff of 50 are uncertified, Kinoshita said, and they are more often the ones to struggle with classroom management.

“There’s a lot of learning to do if you’ve never been through a teaching program,” and a lot of it doesn’t have to do with content, he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)