Want to Cause a Problem in the Future? Name Your School After Someone Famous Today

The Palo Alto United School District ranks among the top districts in the country; according to California’s new accountability dashboard, the three schools’ roughly 2,900 students score at the highest levels on California’s math and English exams. It seems safe to assume that the four deceased educators would be gratified by the performance of their namesake schools.

(The 74: New California Accountability Dashboard Provides Little Light for Poor Families)

But the admiration doesn’t run both ways. Last month, the local board of education voted unanimously to rename two of the three schools by 2018, citing the prominence of David Starr Jordan and Lewis Terman in California’s early-20th-century eugenics movement. They will also add a unit on the history of eugenics to the district’s high school curriculum.

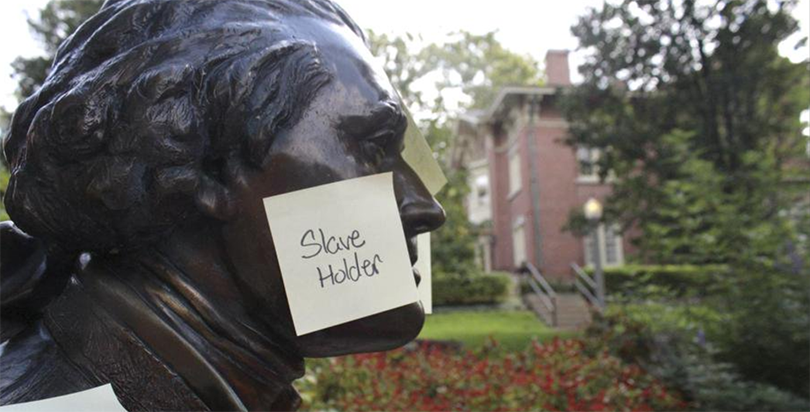

The decision is the latest flash point in a national debate over figures from America’s past whose views — though often not those they were famous for — are no longer acceptable, and the institutions that share their names. The phenomenon has attracted attention especially among colleges and universities, whose presidents and student activist groups have clashed over the veneration of Woodrow Wilson and John C. Calhoun — statesmen revered by previous generations but repugnant to many today for their attitudes about race. But long before today’s undergraduates protested against statues, auditoriums, and mascots on campus, public school authorities around the country had begun moving away from historical monikers.

According to a 2007 Manhattan Institute report that gathered data from seven large states, school naming conventions changed significantly over the past few decades. Prominent people, and especially United States presidents, are adopted much less commonly as signifiers of identity, while hundreds of schools have popped up named after beavers, creeks, mesas, and the space program. According to the report’s authors, the shift reflects a desire to avoid the messy arguments over history, but also a modest retreat from the duty of civic instruction.

When Florida features far more schools named after manatees than Thomas Jefferson, they argue, the country has moved too far in the name of avoiding dispute.

“This community has deep roots, so we did have a lot of alumni who thought that we were dissing the namesakes in a way that was unfair,” said Terry Godfrey, the president of the Palo Alto School Board. “The fact that both Lewis Terman and David Starr Jordan did great things — absolutely, we recognize that, and we know that great men have flaws. But we really felt that once you knew this information and understood their role, how they were a driving force [for eugenics], that changed conversation away from ‘They were men of their times, and a lot of people had the same feelings.’ ”

Indeed, California was a eugenics leader, carrying out one-third of the nation’s more than 60,000 sterilizations in the early 20th century. Few were more ardent in their support than Terman and Jordan, who helped make Stanford one of the nation’s leading universities while also belonging to eugenicist organizations like the Human Betterment Foundation.

Though these names are only recently being reconsidered, individuals tied to more famous American injustices have been marginalized for decades. Twenty-five years ago, the Orleans Parish School Board began a campaign to strike the names of former slaveholders from New Orleans schools. One of them, controversially, was George Washington.

Houston recently moved to alter seven schools named after prominent Confederates, though the plan has met with some pushback. One of the seven, Sidney Lanier, enlisted as a private in his youth before repudiating slavery and becoming one of the South’s most celebrated poets. His proposed replacement, Bob Lanier (no relation), who was mayor of Houston from 1992 to 1998, carries a mixed legacy of his own, including a record of urban development that uprooted one of the oldest black communities in the United States.

All of which raises the question: If the number of taboo historical possibilities is expanding, who or what will supplant them? Current trends suggest longtime school employees, local markers like street or county names, animals, and geographical features.

“We have 17 schools in our system, and they’re not all named after people. They’re named after landmarks and neighborhoods — and people,” said Palo Alto’s Godfrey when asked how the district’s two schools would be renamed. “I don’t know what we’ll pick next, and part of the conversation will be about what person it’s appropriate to name a school after. But we might just go with the kinds of names we have for our other schools.”

The residents of Manatee County, Florida, a target of the Manhattan Institute’s sometimes acerbic report, are making the same determination. A six-week suggestion period is underway for naming a new school, though a district spokesman said that “almost all of the schools named after somebody are for people of local importance,” excepting Lincoln Middle School, which was built during segregation as a high school for black children and had its name grandfathered in.

As this story was being filed, the leading candidate for the new school was the name of a person, though not one that will ring through the centuries: Travis Seawright High School, named after a local livestock agent who inspired students to pursue careers in agriculture.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)