Vouchers Could Be the Big Winner in Trump’s School Choice Plan, but Is That a Victory for Students?

During the campaign, Trump proposed spending $20 billion in federal money to expand school choice programs for children living in poverty. His presidential transition site, which is scant on details, pledges to promote the “expansion of choice through charters, vouchers, and teacher-driven learning models.”

That’s a departure from the Obama administration, which, while backing charter schools, opposed vouchers that allow families to use public money for private school tuition. And while charter school attendance has risen steeply in recent years, enrollment in private schools, particularly Catholic ones, has dropped significantly. This may be because charters have crowded out attendance at private schools, especially in cities where more families could be looking for options outside their neighborhood schools.

Some form of private school choice exists in 29 states, serving nearly 400,000 students, according to EdChoice, a group that backs vouchers, though these programs often face legal challenges over the allocation of taxpayer resources to religiously affiliated schools. Indiana, where Vice President–elect Mike Pence is governor, has one of the most expansive voucher initiatives in the country, which was upheld by that state’s Supreme Court in 2013.

Now, the expansion of such programs could become a federal priority with a Republican president and a Republican-controlled Congress. Perhaps most likely is a reauthorization of the school voucher program in Washington, D.C.

More ambitiously, Trump wants to “reprioritize” $20 billion, perhaps by tapping into Title I funding for poor schools and using it for school choice, including charters and vouchers. This works out to just $1,800 for every child living in poverty, but if state politicians chipped in an additional $110 billion from their own education budgets, as Trump has argued they should, the total would come out to roughly $12,000 per low-income student, similar to the national per-pupil spending average in public schools.

Trump’s vision is still seen as something of a long shot, but if enacted, it would amount to a radical reshaping of how schooling is funded and delivered for millions of students.

“Not only would this empower families, but it would create a massive education market that is competitive and produces better outcomes, and I mean far better outcomes,” Trump said in September.

But that’s far from clear.

There is no precedent for a national private-school-choice initiative at the scale Trump envisions, so it’s difficult to state with any certainty what the outcome might be. But a look back at existing programs offers some window.

(More news, analysis and research on vouchers—and other education issues: Sign up for The 74 newsletter)

The most recent studies show that newer voucher programs are more likely to harm — rather than help — student achievement, while small-scale voucher systems have led to test-score bumps in surrounding districts, and older research shows student gains on outcomes beyond test scores.

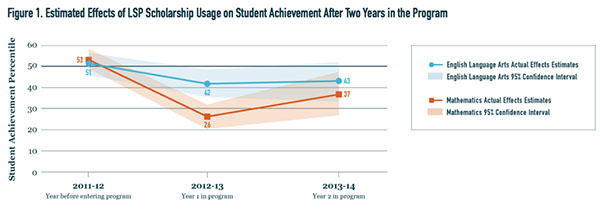

Four recent studies — two in Louisiana, one in Ohio and one in Indianapolis — all showed that using public funds on private-school attendance led to drops in students’ state test scores. These declines are substantial. For instance, one Louisiana study showed that a student who started at the 50th percentile in academic performance dropped to the 37th percentile after two years at a private school.

Previous studies showed that vouchers have generally led to either no overall effects or small gains in test scores, so the recent spate of negative results was surprising. Supporters of school vouchers have offered a variety of explanations for these findings — ranging from the improvement of public schools to the type of test used — but none is definitive.

Joshua Cowen, a researcher at Michigan State University, cautioned against ignoring test scores: “I would be careful about moving the goalposts.”

“As test scores results have been inconsistent,” Cowen continued, “you’ve started to see a lot of the choice people say, ‘It’s other things that really matter.’ ” He agrees that measures outside achievement are important and should be considered as well — his own research in Milwaukee suggests that holding private schools accountable for student test scores leads to noticeable achievement gains for those using vouchers.

The least flattering explanation for the most recent findings is that private school choice is simply not an effective strategy for improving student outcomes. This squares with research suggesting that, when controlling for student background, public schools do a better job of improving math achievement than private schools. Even looking largely at older studies, a recent review showed that although vouchers led to academic gains in countries outside the United States, here they had essentially no effect on student achievement.

Martin West, a professor at Harvard University, says he believes the newer results, but he notes that in some cases, like Louisiana and Indianapolis, the findings are from programs in the early stage of implementation.

Matt Frendewey, a spokesperson for the American Federation for Children, a pro-school-choice advocacy group that reportedly helped Trump craft his plan, said in an email, “15 empirical studies have examined academic outcomes for private school choice participants using random assignment, the ‘gold standard’ of social science. Of these, 11 report positive test score effects among their primary findings. Two studies found no significant effects, and two found negative impact in the early years of study.”

But even when a study’s main finding is that students as a whole do not benefit, descriptions like this often count studies in the positive category if any positive results were found for any group of students — as they have been for African-American students in some cases — even if the overall finding shows no effect. In one positive review of voucher research, many of the studies cited are fairly old, going back to findings from 1998, and quality research using methods other than random assignment are excluded.

As Cowen suggested, some advocates of school vouchers respond that standardized tests do not accurately measure school quality and that academic attainment — how long students stay in school — gives a better picture of vouchers’ impact.

West says the new studies should be “interpret[ed] alongside other evidence that suggests that the option to attend a private school can benefit students, particularly with respect to educational attainment.”

Here, private school choice has a somewhat stronger case.

For instance, a study of Milwaukee’s program showed that recipients of a voucher were more likely to attend and stay in college than similar students attending public schools. Research on D.C.’s voucher system showed that it produced gains in high school graduation, though this was based on self-reports from families rather than measures of actual enrollment. Research showing high school graduation gains should be interpreted cautiously since it’s not clear why these improvements have occurred.

There is also evidence that Catholic schools, in particular, lead to greater school attainment and lower rates of certain risky behaviors, such as teen sex, hard drug use and breaking the law.

Surveys suggest that in some instances families are especially satisfied when attending private schools through a voucher as compared with public schools. For instance, parents of students using vouchers in Washington, D.C., reported higher rates of satisfaction and school safety, though student satisfaction showed no improvements.

A survey of families using vouchers in Indiana found high levels of dissatisfaction with the public schools; the most common reason for attending a private school was the desire for improved academic quality, followed by a perceived “lack of morals/character/values instruction” in public schools.

One national poll of the public as a whole found only mixed support for universal vouchers, with 45 percent in favor and 44 percent opposed. There was less backing for the kind of voucher proposed by Trump, one targeted at impoverished students.

Research showed that New York City’s private-school-choice program led to greater college enrollment among African-American students, though among students overall, vouchers had no impact on college enrollment or graduation.

Studies of voucher programs in Louisiana and New York City showed they had no effect, respectively, on self-reported non-cognitive skills, such as grit and self-esteem, or adult voting behavior, which may reflect the quality of civics education.

Voucher programs showing positive effects on attainment all seem to show positive or no effects on test scores. This suggests that the places that have recently shown negative test results — like those in Louisiana, Indianapolis and Ohio — may not produce the same gains in academic attainment for voucher students.

Test scores clearly have some predictive value: for example, a recent study of Texas’s charter schools showed that schools with negative effects on test scores had, on average, large negative impacts on students’ adult income.

Often the chief argument against school voucher programs is that they will siphon away money and students from traditional public schools, hurting students who remain in the district. As measured by student achievement, this concern has largely not come to pass, and, if anything, private school choice has led to positive effects on students in public schools.

Studies in Florida, Ohio, Louisiana and Milwaukee showed that students in public schools “threatened” by vouchers made slightly larger gains than expected on standardized tests. A review of research showed that competition from vouchers had either neutral or positive effects on public school test scores.

When voucher competition has produced positive results for public schools, those gains often are small and level off after a few years; these improvement may not reach the lowest-performing schools. Qualitative research suggests that schools often respond to competitive pressure by improving their marketing efforts rather than their academic programs. It’s not clear whether results from these smaller-scale programs would apply to the national system envisioned by Trump.

(The 74: Whitmire — Donald Trump, the Best (or Worst) Thing to Happen to School Choice?)

Some argue that a plan of this scope would eradicate public education. Former Democratic representative George Miller told Politico that the initiative “would be one of the great train robberies of America.” The sweeping vision that Trump has laid out would indeed likely have massive fiscal implications for public schools, many of which might be forced to close if they lose too many students, while providing a potential boon to private and religious schools.

“School vouchers” mean different things in different places. There is a great deal of variation from program to program regarding who is eligible (just low-income students, or those with special needs, or all students), what rules there are for participating schools (whether they can use selective admission or must administer the annual state test) and how much money is attached to the voucher.

Although Trump’s campaign plan and transition site offer few of them, the nitty-gritty details are likely highly relevant to his initiative’s success or failure. West, of Harvard, argues that voucher programs need some oversight measures to ensure quality: “I do think [the latest voucher research] suggests the need for a thoughtful approach to regulation when it comes to efforts to expand parental choice.”

Robin Lake, of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which supports many school choice initiatives, said she believe there needs to be a focus on quality: “My fear is [that] a big ideological push for choice as an end, not a means, is a dangerous prospect. It’s not only dangerous for getting schools started that may not be effective, but it’s also dangerous for long-term politics.”

Disclosure: The 74’s Editor-in-Chief Campbell Brown sits on the American Federation for Children’s board of directors. Betsy DeVos chairs AFC’s board and The Dick & Betsy DeVos Foundation provides funding to The 74, The American Federation for Children sponsored The 74’s 2015 education election summit.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)