Vander Ark: Design Thinking and Other Learning Priorities to Educate Today’s Students for the Coming Automation Economy

From a drafting board to Autocad, from a legal pad to a tablet, from eight-track tapes to downloads, my 40-year career spanned the information age from beginning to end. As monumental as those changes have been, my granddaughter may see an order of magnitude more change in her life.

The election of 2016 signaled the end of the information age and the beginning of the automation age. Barack Obama was elected by social media; Donald Trump was elected by algorithms that exploited social media. By 2016, we all lived in information gullies co-constructed by bias and bots. Ironically, major-party candidates fought a 1990s battle while the rise of artificial intelligence became apparent in every aspect of life and work.

With terrible force, 2017 ended with a series of once-in-a-century storms heralding a new era of urbanization, globalization, and automation, human systems colliding with natural systems in unpredictable ways.

We’re one year into this new age, an era of novelty and complexity. We live and work with smart machines and are influenced by algorithms we don’t understand. Most jobs have been or will be augmented, and then many will be automated. Displacement will vary by sector and geography, but it will be significant and it will begin before today’s middle school students graduate and join the workforce.

This automation age is being driven by artificial intelligence, big data (and internet of things), and enabling technologies (like robotics and CRISPR).

The age of automation offers unparalleled opportunity for contributions to health, longevity, safety, and prosperity. But without forward-looking civic leaders and quick action, the benefits will be concentrated, leading to conflict and more reactionary politics.

How to prepare?

How do we help young people prepare for lives full of novelty and complexity? After a two-year study of the influence of artificial intelligence (and exponential change more broadly) and a dozen community conversations, my team concluded there are four new learning priorities:

- Innovation mindset: a combination of growth mindset, maker mindset, and team mindset — in short, young people should learn to recognize the value of effort, initiative, and collaboration.

- Social-emotional learning: managing yourself and social interactions, making good decisions.

- Design thinking: attacking complex problems with empathy and iteration — using a repetitive process with the aim of approaching a desired goal, target, or result.

- Self-directed learning: staying curious, building deep subject expertise — repeatedly — and creating lifelong learning habits.

Design thinking may be the least familiar priority on the list — and it might be the most important, because many of the problems and opportunities we face are new. They often sit at the boundary of traditional disciplines, at the intersection of man-made and natural systems. These challenges require a new approach to problem identification and solution.

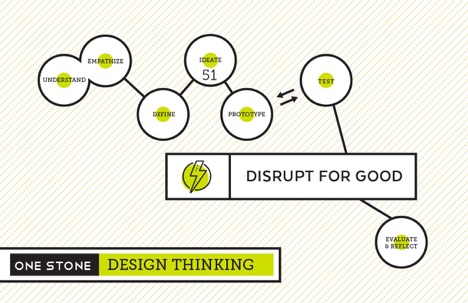

A five-stage model called design thinking has been advanced by the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (d.school). The steps to this model are empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test.

Design thinking is central to the approach at a number of innovative schools, including Design Tech High in the Bay Area and High Tech High in San Diego. Boise, Idaho, nonprofit One Stone makes design thinking central to the best after-school work experiences and community service programs I’ve seen. It’s also integrated across the curriculum at the new One Stone high school. Their process, adapted from the d.school, suggests that it may take more than 50 iterations to develop the right solution. One Stone students learn to “51 it.”

In higher education, the best example of design thinking is found at Olin College, near Boston. From week one, students learn, research, design, make, and manage.

When design thinking is incorporated into the curriculum, it teaches all the other core skills: innovation mindset, empathy, and self-direction.

Project-based world

Most work is now conducted in projects. More than 4 in 10 high school graduates work in the freelance economy (with that number likely to increase to a majority within 10 years), and probably as many who go to work for others end up working on or leading project teams.

When I was an engineer, most projects I managed were well defined. The design phase was a matter of applying best practices to a known problem. What’s new today is the number of problems for which there is no known solution, what Harvard’s Ronald Heifetz called adaptive challenges. Design thinking is particularly well suited to addressing these new problems and opportunities.

Whatever the mix of known and unknown challenges a young person faces, the best preparation for a project-based world is learning to manage extended challenges — some well defined and others open-ended design tasks.

Most professions in the 21st century exceed the capabilities of any individual and require cross-functional teams to deliver properly. According to Dr. Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal, medicine has moved past the individual craftsman to delivery by teams. “It’s no longer an individual craft of being the smartest, most experienced, and most capable individual,” he said. “It’s a profession that has exceeded the capabilities of any individual to manage the volume of knowledge and skill required. So we are now delivering as groups of people.” Gawande said that what is most needed in professional preparation now is the study of the science of teams.

Smart teams use shared protocols like design thinking, exercise empathy for each other and their customers, and manage themselves and reflect on their progress.

MIT’s Eric Lander has said that “in a few years, every biologist will be computational.” The same will be true for doctors, mechanics, economists, water managers, and soldiers — nearly every field is being transformed by the combination of artificial intelligence, big data, and enabling technologies. As a result, advances almost always involve assembling a big data set, a task that requires creativity, partnership, analysis, a lot of cleanup, and a good truth detector. Value creation is being led by people passionate about a cause, who are adding data science to their quest.

For young people facing novelty and complexity, critical attack skills include design thinking, project management, data science, and delivering in teams.

Tom Vander Ark is CEO of Getting Smart and author of Getting Smart, Smart Cities, and Smart Parents. He previously served as the first executive director of education for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and as a public school superintendent in Washington State.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)