Using Medicaid to Fund More Mental Health Supports for Schools

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As a former school counselor, Quarry Williams spent a lot of time getting to know his students when he became coordinator of the Honor Opportunity Purpose Excellence (HOPE) alternative learning program in Edgecombe County Public Schools. He remembers forming a bond with one student in particular.

When the student broke school rules, though, Williams was forced to dole out a consequence. What happened next broke his heart and opened his eyes.

“He came to me and said, ‘What happened to you Mr. Williams? You don’t like me anymore,’” Williams recalled. “That’s when I understood that I really have to have someone in my building that can assist me in making sure that the students have a safe place to go, where they can talk, decompress, and learn resiliency skills and coping skills — [someone] other than myself.”

He needed a school social worker, but the district — like many others across the state — was already short of the nationally recommended ratio. And it lacked the budget for more.

Through participation in a strategy-building community cohort, Williams found a solution that the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) believes could be a solution for districts and charter schools across the state.

Williams, leveraging starter funds from a grant, found a way to bill student mental health services to Medicaid and convinced the district to earmark reimbursements for his health and wellness program to create a sustained social worker position.

A growing problem with elusive solutions

Several factors are exacerbating mental health issues for students today. Local education leaders, state leaders, and President Joe Biden are calling attention to a student mental health crisis.

But many schools lack resources to meet the needs. For years, schools across North Carolina have operated far below nationally recommended ratios for mental health support personnel. In 2018, the ratio of school counselors to students in North Carolina was about 1 to 386. (The National Association of Social Workers recommends 1 to 250.) It’s the product of both underfunding and a timid professional pipeline.

A popular solution, in some districts, is temporary funding through grants. But there’s a catch to this approach.

“What happens with the student when those funds leave?” Williams asked. “The student still has the need. I feel like it is much worse if you get the help that you need and then all of a sudden it goes away. Especially with students that have trauma, that’s another barrier for them — like, this person just left me.”

Taking the grant, but after establishing a plan for what’s next

For the HOPE program, this began while addressing the question — “How can a community build strategy around learning, healing, and connecting?” — as part of a group convened by the Rural Opportunity Institute for the Resilient Leaders Initiative in Edgecombe County.

Through this work, Williams conducted interviews and brainstormed with community members to surface nearly 100 ideas to help meet community needs. Williams and his team tested ideas and reflected on efficacy — landing on the big one for HOPE: school-based mental health support.

The Resilient Leaders Initiative’s accountability board was prepared to award HOPE a grant to fund a social worker position. Williams knew the funds would get students help right away. Afraid of offering a “Band-Aid solution,” though, he wasn’t sure about accepting it until he knew how to make it sustainable.

“Without Mr. Williams, we all would have taken that idea of mental health support, the accountability board would have given this grant, and their services might have looked very similar to what’s happening now — but the services would have gone away when the grant was over,” said Seth Saeugling, co-founder of Rural Opportunity Institute. “Thanks to Mr. Williams push on [sustainability], it just took it to a whole different level.”

Williams reached that level after several nights grappling with the challenge. Why couldn’t he replicate the system currently in place for many rehabilitation services for physical disabilities? After all, schools bill Medicaid for things like speech therapy often.

How the HOPE Medicaid cost-recovery model works

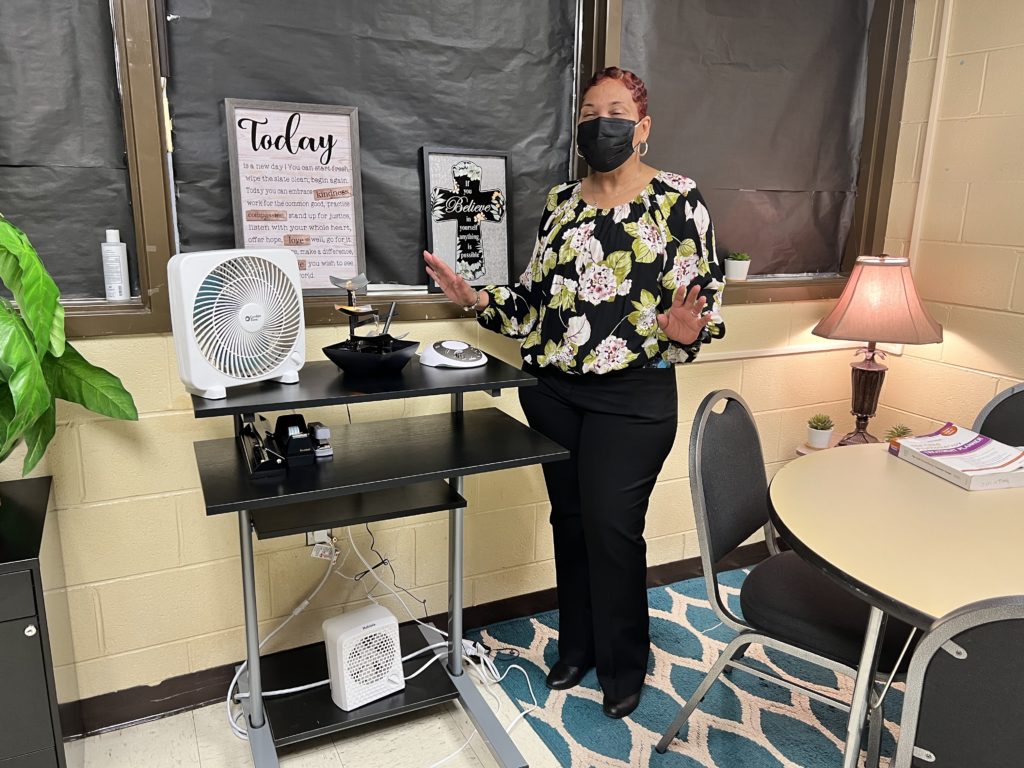

The process starts with a family meeting for students referred to the program. The district’s superintendent, Valerie Bridges, includes recommendations for mental health support in these referrals when appropriate. In those cases, Williams introduces the services that Marlo Walker can provide inside the school building during the initial family meeting.

Walker is the social worker HOPE hired using grant funding. The reimbursements from billing her services to Medicaid accumulate in a pot of money used to sustain her position.

Many families lack insurance or resources to get students to outside treatment providers during the work day, Williams said. Many families express great interest in utilizing Walker’s services at school. If the student qualifies for Medicaid, Williams then writes treatment services into a formalized plan and introduces a set of forms that guardians must sign.

The formalized plan is a necessary step. In order to qualify for Medicaid reimbursement, services must be “medically necessary” to students. Schools often use formalized plans like Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) or 504 plans for students with disabilities to substantiate mental health needs.

But many of Williams’ students don’t fit that description. To formalize need for services, he creates a Behavioral Intervention Plan (BIP) for the student, reviews the BIP with families, and presents them with Medicaid intake forms that he’s redesigned to become more reader-friendly. Walker then onboards students into an online platform, working with hundreds of codes to figure out which designation would be least restrictive for the student.

“They don’t want to slap intense, restrictive labels on kids that could stigmatize or harm them — like Oppositional Defiant Disorder,” Saeugling said of HOPE’s process. “So they try to find codes that align to the need, but have less stigma and are least restrictive.”

After students are in the online system and services start, Walker bills her time and the district submits the billing for reimbursement through Medicaid. An important step: Williams asked district leaders to create a specific code for Medicaid reimbursement dollars. That code earmarks the money for HOPE, ensuring the program maintains funding for the social worker position.

Making support available to every student in school

Walker previously worked at an agency that contracted with another district to provide school-based mental health. She remembers walking into those schools and meeting so many students that needed — and even wanted — her help. Her agency limited her to the students assigned to her caseload.

“I prayed that they had something like this for the kids,” Walker said of her prior experience. “The principals used to try to get me to see the other kids but I was not allowed. We couldn’t do it.”

Now, even though Medicaid reimbursement will fund her salary, she’s employed to provide mental health support for every student at HOPE.

“I think this is the best program that I’ve ever seen,” Walker said. “It works for the kids. I get to be present and I’m working with all the kids and I see a difference.”

After starting the job in January, she’s already celebrating wins. Walker thinks about one student referred to HOPE from a psychiatric center admission after experiencing a breakdown in school. After several months at HOPE, he’s preparing to return to his primary school. Williams had worked with the student as much as his other duties allowed prior to Walker’s hire. He said Walker has made “a big difference” with the student since she arrived.

“Now he feels ready to go back,” Walker said. “He told me he has the tools and he’s ready to go back to school. That’s where the heart is, that’s the blessing in this work. As soon as a student opens that door and says, ‘I need to talk to you,’ — that’s a difference. That student knows they need something and they know it’s normal to ask for help.”

Can other districts replicate Medicaid cost recovery?

Williams said support from the district superintendent and Robert Batts, director of secondary education, was instrumental. He’s sure they may have had their doubts when he first proposed the plan. They never communicated doubts to Williams, though.

“What I like about this is it was something innovative, something never done before,” Williams said. “I’m quite sure people had fears of what might happen because it’s never been done before, but they supported this vision. And now you’re seeing it in living color and seeing the possibilities of what can happen.”

Lauren Holahan, coordinator for the state systemic improvement plan, Medicaid, and school mental health in DPI’s Exceptional Children Division, also lifted up the cross-systems collaboration within the entire county.

“At HOPE, they really figured out the communication channels and role responsibilities for getting reimbursements,” she said.

Holahan has worked with Exceptional Children personnel and district financial officers to maximize Medicaid benefits in the past. She said the policy documents guiding districts and charters are decades old. The documents are reflective of a time when the emphasis was using funding on rehabilitation for students with physical disabilities. There wasn’t as much focus on mental health and behavioral supports.

But she sees no reason that other districts can’t do what HOPE has done.

“It doesn’t require [being] a specialized program like HOPE to do this,” said Holahan, who wrote her dissertation on the Medicaid program. “If we want to find a couple of support positions at two high schools in our [public school unit], this is a way to do it.”

That’s the exciting part for Williams. He’s hopeful that others in the state will try to replicate HOPE’s success. Particularly those places where grant money is funding specialized support personnel.

“I think it’s big, it’s inclusive,” Williams said. “Everybody needs help at some point in time and I would hate for someone to need help and not be able to access it. So if we’re able to meet that need, why not?”

This article first appeared on EducationNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)