Use It or Lose It! How Age Affects Cognitive Skills

Hanushek: New research shows that reading and math skills can remain strong into old age for people who use them regularly.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Conventional wisdom tells us that cognitive skills continue developing until people reach their early 30s and then begin a long fall. However, that conclusion does not come from following individuals as they age. Instead, it comes from comparing the math and reading skills of individuals of different ages at a single point in time.

The problem is that people of various ages have different educational experiences, different jobs and different circumstances, affecting how they develop and retain their skills.

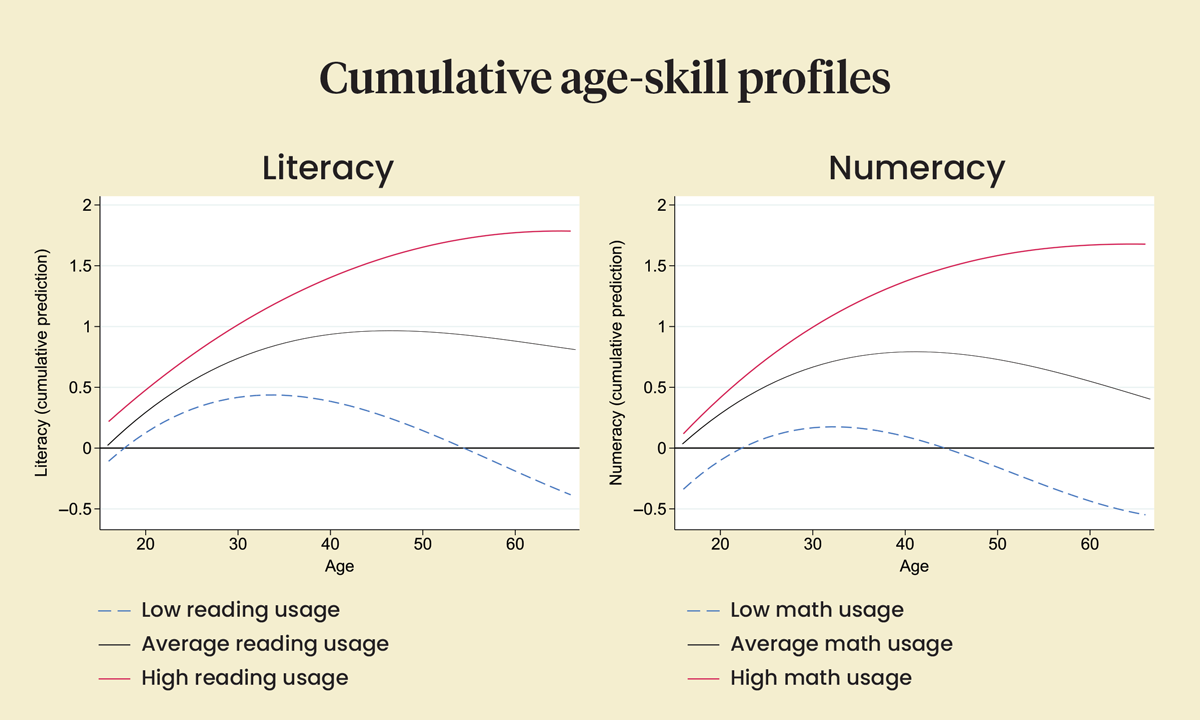

In new research, my colleagues and I find that skills typically rise until the 40s, after which reading skills gently fall and math skills more steeply. Even here, however, the story is not so simple. These averages mask the fact that any decline is closely tied to how much the skills are used.

Simply put, people who read and do math on a regular basis hold on to those skills at least into their 60s.

Economists are interested in understanding this because reading and math skills are closely related to economic outcomes. More highly skilled individuals tend to earn more, and countries with more skilled populations grow faster. Here is the big issue: Most developed countries of the world have aging populations. Does this then imply worse economic outcomes as we go forward?

The research challenge in answering this question has been a lack of appropriate data. For the most part, existing data on age and skills do not come from observing a representative sample of people as they age. Instead, they come from comparing the skills of different people of different ages, say one at 30 and one at 40, and assuming that after aging for 10 years, the 30-year-old will look like the 40-year-old.

But these two people grew up in different circumstances, with differing quality schooling and other factors that might affect their skills. Thus, any effects of aging are mixed up with other societal factors.

We overcome this problem by using unique German data that follow a representative sample of 3,263 adults over a three- to four-year period. At the initial survey and again at the later survey, the individuals are given the same reading and math test. Thus, it is possible to observe directly the impact of age on skills.

What we found was that skills, on average, continue to increase into the 40s, and they never dip below the levels the individuals enjoyed in their 20s.

Perhaps the more important finding is that even this later decline is not inevitable. These average patterns hide the dramatic differences in aging between those who use literacy and numeracy skills consistently at home or work and those who do not. The survey data asked about the frequency of doing separate items such as “calculating prices, costs, or budgets” for math or “reading letters, memos, or e-mails” for reading.

Those with above-average usage never showed declining skills at least until age 65, when our data ended. Those who weren’t much using math or reading skills peaked in their early 30s.

Interestingly, based on assumed high-skill usage, some previous analyses followed the skill patterns for white-collar and highly educated workers. When we look at these factors, we find the same answers: Among professionals or highly educated individuals, those who use the skills never show declines with age, but those who do not use the skills do, in fact, start to decline. Women show a sharper drop in numeracy skills as they grow older than men, perhaps based on educational background or career choices.

While our results, in principle, offer some consolation for countries with aging populations, they also highlight the importance of policy attention toward not only the accumulation of skills in schools, but also their retention through using those skills and pursuing lifelong learning.

Fostering expanded learning opportunities takes on increased importance with such societal changes as the broad introduction of various forms of artificial intelligence, which could force a large number of people to change what and how they are doing their work. Unfortunately, while the idea of lifelong learning is frequently discussed in policy contexts, little has been done to make it a reality.

The Hoover Institution provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)