University of California Rejects Proposal for Campuses to Hire Undocumented Students

Ten regents voted in support of the motion to rescind the proposal for a year and six opposed

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

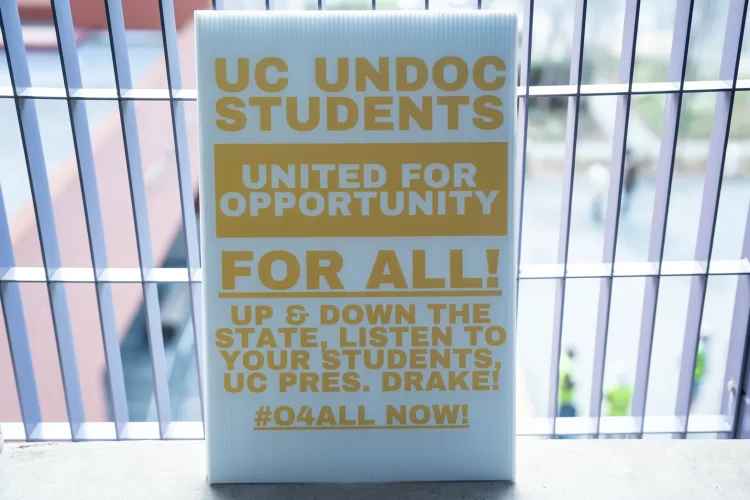

The University of California suspended for a year its plan to allow undocumented students to acquire campus jobs, crushing a student-led movement more than a year in the making.

The decision all but halts an effort by UCLA law professors and student advocates to create a pathway for the estimated 4,000 undocumented UC students to earn a paycheck legally. While many students without legal immigrant protections receive state financial aid and have their tuition waived, those students are often on their own financially to cover rent, food and other necessary expenses to continue their studies. These students also are blocked from receiving federal grants, further intensifying their fiscal strain.

“We have concluded that the proposed legal pathway is not viable at this time,” said Michael Drake, president of the UC, at today’s regents meeting. He said the proposal is “inadvisable” and “carries significant risk for the institution and for those we serve.”

However, “as new information becomes available, we will evaluate that information, and if appropriate, move ahead,” he said.

Regents, who make up the top governing board of the UC, voted to formally rescind a policy it adopted in May to explore implementing the hiring plan. Undocumented students in the audience screamed through tears, some who were on a hunger strike since Tuesday to pressure the UC to adopt the hiring measure.

“Cowards!” a student yelled. “Shame,” another said. “I hope you live with this for the rest of your life,” said another.

“I’m deeply disappointed that the UC Regents and President Drake shirked their duties to the students they are supposed to protect and support,” said Jeffry Umaña Muñoz, a UCLA undocumented student and leader at Undocumented Student-Led Network, in a statement. “We as UC students deserve so much more from our university leadership. This is not the end of our fight for equality.”

Ten regents voted in support of the motion to rescind the proposal for a year and six opposed. One voter abstained.

“I can’t think of a moment where I’ve been more disappointed sitting around this board table,” said John Pérez, a UC regent and member of a working group to explore the plan. He voted no.

The UC would have been the first university to adopt such a measure, said Jorge Silva, a senior spokesperson for the UC.

UC’s general counsel, Charles Robinson, and his legal team were “very skeptical of the legal theory,” said Merhawi Tesfai, a UC regent and graduate student who votes on the board. Tesfai was also part of the working group and wanted the UC to hire undocumented students.

Drake in his comments today said that his office consulted with legal experts “inside and outside the university.”

Tesfai said the general counsel’s office sought legal analysis from multiple outside law firms, and their conclusion was that “this wasn’t something that they would recommend and that it wouldn’t be legally viable,” Tesfai said, summarizing comments that Robinson and Drake made to him and other regents.

After today’s vote, he and a few other regents consoled the crying undocumented students in attendance at the UC San Francisco meeting space. “It was all justified anger,” he said.

Legal theory

Core to the novel legal argument of the UCLA coalition Opportunity For All is that while a 1986 federal law bars employers from hiring undocumented immigrants, the UC, as a state agency, is exempt. “Under governing U.S. Supreme Court precedents, if a federal law does not mention the states explicitly, that federal law does not bind state government entities,” the coalition’s 2022 legal memo said. Nothing in that federal law “expressly binds or even mentions state government entities.”

Pérez said that “we have gotten so focused on the question of what the law clearly says today that we’re losing sight of the moral imperative of what the law should be interpreted as being.”

But Drake said the risks were too great. Human resources employees and legal staff “might be subject to criminal or civil prosecution if they knowingly participate in hiring practices deemed impermissible under federal law,” he said. He said the UC “will be subject to civil fines, criminal penalties, or debarment from federal contracting if the university is found to be in violation of the Federal Immigration Reform and Control Act,” the 1986 federal law. The billions in federal research grants could also be at risk, Drake said.

The argument to hire undocumented students has the support of some of the country’s most prominent immigration law scholars, who signed the legal memo backers of Opportunity for All published in 2022. Meanwhile, more than 500 faculty have signed a December letter saying “we will hire undocumented students into educational employment positions for which they are qualified once given authority to do so by the UC.”

Student advocates of Opportunity For All pushed the UC Regents to take the group’s legal theory seriously. Last May, the regents voted to consider whether the UC could hire undocumented students and what that process would look like. Students were initially jubilant, but months later were furious when the UC blew past its own deadline on how to proceed at the November meeting. Several dozen students risked arrest by crossing the stanchions separating them from the regents, shutting down the meeting. That prompted a meeting between advocates and several regents.

Those regents told the students then that they were committed to a full roll-out of the plan by this month, but they were not speaking for the full board.

“It is deeply shameful that the UC is holding them back from achieving their full potential,” said Ahilan Arulanantham, a UCLA immigration law scholar and one of the architects of the legal theory arguing undocumented students can legally work at the UC.

Recent federal rules

The ability to work legally is a matter of survival for immigrants in the U.S. But while more than half a million undocumented immigrants who entered the U.S. young are allowed to have jobs through the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, federal courts have halted the federal government’s ability to accept new applications. But even if the courts permit new applications, most of today’s young undocumented immigrants wouldn’t benefit. That’s because DACA applies to individuals who arrived in the U.S. by June 15, 2007 and are at least 15 years old upon applying, leaving most young students today ineligible.

In 2023, just 1% of all DACA recipients were under 21 years old.

“As a leader of an American Indian nation, for us to sit here and be so concerned and keep talking about risk when the students and their families have gone through so much risk just to get here, only can strike me as patronizing,” said Gregory Sarris, a UC regent.

The UC has a history of upholding legal protections for undocumented students. The university sued the Trump administration in 2017 for ending the deferred action program. That legal saga culminated with a Supreme Court decision upholding the program in 2020. DACA lived on, but lower court decisions since then have blocked the Biden administration from processing new applications.

But Pérez said the UC didn’t lead, as Drake said, but reacted to student, faculty and community advocacy to challenge the Trump administration. Roughly 17,000 Californians don’t qualify for the deferred program because of decisions by the Trump administration and the courts.

Donald Trump is likely to emerge as the Republican nominee for the Oval Office. A Trump presidency could lead to a redux in the fight between the UC and the federal government over immigration rights for the country’s young residents.

“What happens if we have a new administration?” asked Jose Hernandez, a UC regent who supported the hiring plan. “I don’t even think this is going to be considered to be implemented, to tell you the truth, so I think we’re squandering a great opportunity.”

There had already been pushback to the UC proposal from some Republicans, among them Rep. Darrell Issa of San Diego County. He shot off a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom warning that California couldn’t “pick and choose which federal laws to follow and which to declare null and void.” If the UC system did approve the policy change, he wrote, “please inform Congress how the system intends to refund its current federal funding, as well as provide a detailed estimate of the fiscal impact to students by foregoing future federal assistance.”

Work and financial aid

Abraham Cruz, 25, is a UCLA senior and undocumented. His DACA status lapsed a few years ago and he has been unable to renew it, so no employer can legally hire him.

He found a loophole, but it’s uncommon: Cruz is part of a labor cooperative where he’s his own boss. He consults clients on immigration policy, research and writing, he said.

Still, he’d rather have a campus job, where managers know to prioritize students’ academics over work. Or he could work with a professor and pursue research in his field of labor studies.

Drake, UC’s president, said in November that he wants to protect students from any legal consequences, but Cruz said students are already assuming the risk of working under the table or in dangerous jobs, often below minimum wage.

“I don’t know what the UC thinks, but if it doesn’t offer jobs on campus students are going to have to find a way … to come up with that money,” he said. “The best thing the UC could do is provide these safe jobs for students.”

Pérez echoed that view. “We can fool ourselves into thinking that our students aren’t working. They are,” he said. “They’re working in underground jobs subjected to inhumane and horrific conditions.”

Another option for undocumented students is receiving an academic fellowship. But fellowships and scholarships are financial aid — and no student can receive aid above the state cap, which is equal to what a campus calculates is the cost of attendance. Even the most generous financial aid package from the UC still expects a student to find $8,000 to $10,000 of their own money each year to pay for tuition, housing, food and other costs. Academic fellowships and outside scholarships can’t exceed that $8,000 to $10,000 personal contribution.

And while students with income could see their financial aid decrease, most undocumented students have low enough incomes to qualify for California’s marquee financial aid tool, the Cal Grant, which waives tuition.

“I’m frustrated, I’m pissed off, I’m angry that we’re at this point,” said Keith Ellis, a regent representing UC alumni. “I feel like we’ve led on the students, that we’ve lied to you in some ways, and for what it’s worth, I apologize.”

This story was originally published in CalMatters.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)