Union Report: When NEA Speaks to National Press Club, the Faces Change but Song Stays the Same

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears Wednesdays; see the full archive

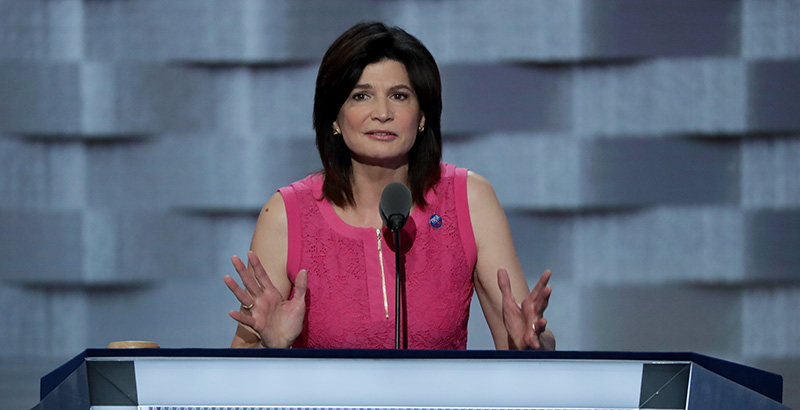

Last Friday, National Education Association President Lily Eskelsen García delivered a speech to the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

She denounced the policies of the Trump administration while calling for common ground because “most people are good people — they want something good for kids and their families and their communities. We can argue over what’s a good idea or a bad idea, but time and time again, I’ve seen people come together when you can show them a plan that makes sense.”

Eskelsen García’s plan is “to make every public school as good as our best public schools.” This can be done, she said, through equal access, equal opportunity, and equal respect, but not through “test prep and cutthroat competition with private charters.”

She went on to describe wonderful NEA-supported programs in Texas, New Mexico, Minnesota, and New Jersey.

While the White House might have objected to the tenor of Eskelsen García’s remarks, there was little to stir up the masses outside the Beltway. NEA presidents make periodic visits to the National Press Club, and they usually offer up a similar vision of utopia if only their agenda were followed.

I am cursed with a long memory, and so I recall the original NEA president National Press Club speech. Bob Chase delivered it 20 years ago, and he used the occasion to introduce the concept of “new unionism.”

New unionism was prompted by a dire internal report NEA commissioned from a public relations firm that concluded the union had no credibility in the education reform debate. The firm suggested NEA’s image-improvement campaign “should be launched in a speech by President Chase in which he acknowledges the crisis, says some things for their shock value to open up the audience’s minds (e.g., there are bad teachers and our job is to make them good or show the way to another career), and then details the association’s substantive programs to improve public schools — those already in existence and those that will be expanded or launched in the months ahead.”

Chase did just that. He admitted NEA had been “a traditional, somewhat narrowly focused union” that was “utterly inadequate to the needs of the future.”

He said, “America’s public schools do not exist for teachers and other employees. They do not exist to provide us with jobs and salaries.”

Chase went on to follow his PR firm’s advice and say, “There are indeed some bad teachers in America’s schools. And it is our job as a union to improve those teachers or, that failing, to get them out of the classroom.”

Just as Eskelsen García would do 20 years later, Chase called for greater collaboration among stakeholders, but his plan to improve schools contained items quite different from those on Eskelsen García’s list, including higher academic standards, stricter discipline, an end to social promotions, and less bureaucracy. He then described wonderful NEA-supported programs in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

One other 1997 union effort Chase mentioned stands out noticeably today: “Imagine the president of a local NEA union taking the lead in founding a public charter school, a new school that she and her colleagues manage by themselves, without a principal. I just described the work of Jan Noble, president of our affiliate in Colorado Springs.”

NEA’s 1996 Charter School Initiative deserves a retrospective of its own, but as failures go, it didn’t come close to the debacle Chase also touted in his Press Club speech: Disney’s Celebration Teaching Academy in Orlando, Florida.

“It will be for educators what a teaching hospital is for doctors: a place where teachers from around the nation can come to sharpen their skills and be exposed to best practices,” Chase said. “NEA professionals on site will help to shape the curriculum and to direct the academy’s Master Teacher Institute.”

He told the audience that “the Celebration Teaching Academy is exactly what the new NEA is all about: a commitment to lifting up teachers as professionals and to revitalizing public education.” Chase put NEA’s money where its mouth was, contributing $500,000 to the academy.

The academy never got off the ground. It was “stillborn, a victim of educational infighting,” according to a husband-wife pair of journalists, Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins, who moved with their kids to Orlando specifically to take part in the Disney community and schooling experiment. The experience was so disastrous they wrote a book about it.

In her speech, Eskelsen García emphasized the importance of taking action. Chase was no different. “I deal in practical, concrete, tangible changes. I deal in results,” he said.

“The new NEA is about action,” he told the Press Club audience. “And, on that score, I challenge the American public: Watch what we do, not what we say.”

In the 20 years since, we have watched what NEA does. The evidence suggests there’s no point in listening as it tells us what it’s going to do — again.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)