Union Report — NEA Conference Reveals Disconnect Between How One Teachers Union Trains Its Staff vs. How It Talks in Public

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears Wednesdays; see the full archive

The National Education Association spends almost $34 million annually on communications, so it’s easy to determine the organization’s position on any number of issues. But the union’s public messages can be quite different from what’s shared internally with officers, staff, and the NEA’s most dedicated activists.

Each year NEA holds a leadership summit to “develop activist leaders and prepare them with the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to lead a relevant and thriving association.” The 2018 conference was held last month in Chicago and featured dozens of seminars and workshops to assist local and state activists in navigating their affiliates through tough times.

These summits often provide details about NEA operations previously hidden from public view, like details of the Jefferson County Education Association’s school board recall strategy. Last year one workshop described “collective action/mass demonstrations” as “a good show, but should be linked to a lobbying effort.” It’s unlikely that anyone at NEA headquarters still describes such actions that way.

The most informative of this year’s sessions involved the union’s media relations. In “Media 101: Using the Fourth Estate to Deliver Your Message,” NEA staffers told activists to think of the media as “customers,” but they had unusual advice about what to do when a “customer” calls.

“Tell them you are going into a meeting and you need to call them back,” reads a PowerPoint slide from the presentation. However: “Before hanging up, start interviewing them!”

Apparently the ruse is meant to buy time for a little research. Before talking on the record, the activist is supposed to determine the angle of the story, whether the reporter works for “a legitimate media outlet,” and if it is “friendly.” Then the activist should check to see whether NEA or the local/state affiliate has talking points on the topic.

During an interview, the activist is advised, “Get across the points you think are important, regardless of the question” and “answer the question you want to answer.”

An example of how this might work appeared in another session, titled “Beating Back Vouchers: Case Studies in Success.” The presenters provided what they described as “hands down, our best message”: “Instead of investing in public education, voucher programs all take money away from our public schools.” That phrase should be coupled, they advised, with “hands down, our best stat”: “If we have money to spend, we should invest in public schools where 90 percent of children go, instead of diverting money to private schools where only 10 percent go.”

Included in this advice was what not to say:

Do NOT say CHOICE

• Not even if someone else says it first.

• Not even if you say “so-called choice”

Do NOT say FAILED SCHOOL

• Reject this label. Instead talk about what schools need to be successful.

The real eye-opening stuff was presented by Ramona Oliver, NEA’s senior director of communications, in a session titled “Building Member Loyalty.”

Amid some standard public relations guidance about staying on the offensive, using third parties to validate the union’s message, and building brand loyalty were some startling statistics culled from NEA surveys of members.

The union asked this question to members who currently work in states that allow unions to charge representation fees to non-members:

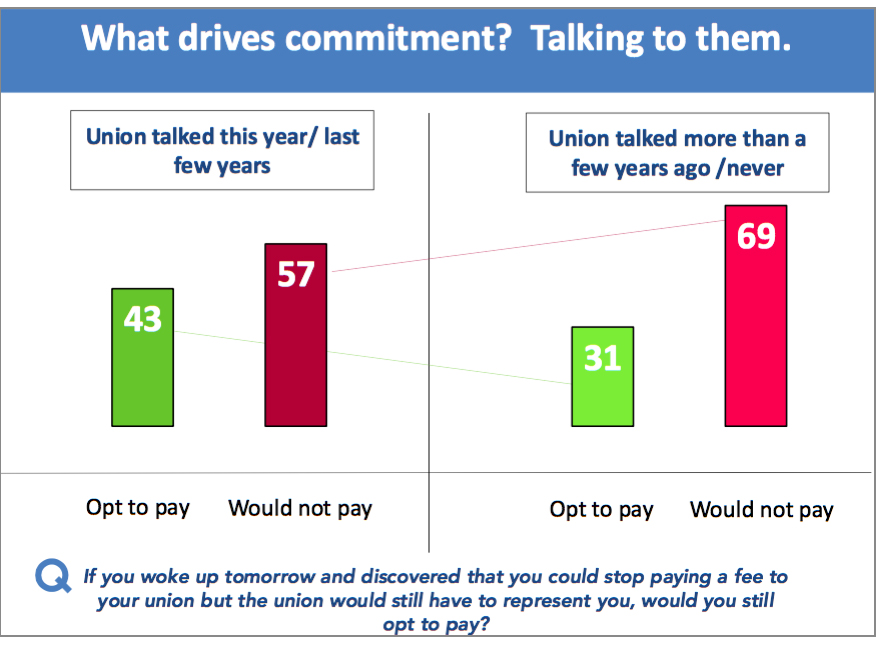

“If you woke up tomorrow and discovered that you could stop paying a fee to your union but the union would still have to represent you, would you still opt to pay?”

Among members to whom the union had talked within the past few years, 57 percent said they would not pay. If the union had not talked to them in the past few years, that number jumped to 69 percent.

The survey then asked a follow-up question to those who said they would not pay: “What if you found out that opting not to join or pay a fee could weaken your union or employee association to the point where it could no longer negotiate your wages, benefits and working conditions. Would you still choose to stop paying?”

NEA found that between 38 percent and 81 percent of those “won’t pay” votes were then reversed, depending on the respondents’ previous interactions with their unions.

Oliver presented this information to illustrate the importance of personal contact with members in staving off the worst effects of an adverse U.S. Supreme Court ruling on agency fees in the Janus case. But even with such a loaded follow-up question, the survey indicates NEA’s immediate membership loss might be much larger than I previously guessed.

A little basic arithmetic using the above numbers suggests that under the very-best-case scenario NEA would immediately lose about 11 percent of its members in agency fee states. Under the worst case, the union could lose about 36 percent.

Another slide from Oliver’s presentation said NEA has a “deeper vulnerability among agency fee payers,” by which I believe she meant that teachers who are currently fee payers will not become members in any great number.

In-person contact was the key to maintaining membership, activists were told. When dealing with agency fee payers, they should “talk about how the union amplifies their voice.”

Unfortunately for NEA, that is the crux of the matter. People who have become fee payers feel their voice is being silenced by their union. That is true even among many who walked out in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona. Teachers may seek other amplifiers, or build their own.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)