Union Report: Are Teachers Quitting at Record Rate? Actually, They Leave Their Jobs at Lower Rates Than Almost Everyone Else

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears Wednesdays; see the full archive.

The Wall Street Journal left a present under the tree for the education press when it published a Dec. 28 story with the headline “Teachers Quit Jobs at Highest Rate on Record.” The Journal cited U.S. Department of Labor figures revealing that public education employees quit at a rate of 0.83 percent per month in 2018, the highest rate since that statistic was first compiled in 2001. The rest of the story was devoted to why this might be so.

Media outlets from the left, right, and center picked up the story. All of them cited the Journal’s findings, but none of them bothered to go to the source data for additional context — which do not support that conclusion. Somehow, context doesn’t lend itself easily to alarmist tweets and subheads about teachers who “abandon the classroom in droves.”

To be fair, the Journal reporters included some context about the numbers, and they don’t write the headlines. But their story clearly repeats the erroneous narrative that public education is undergoing a retention crisis.

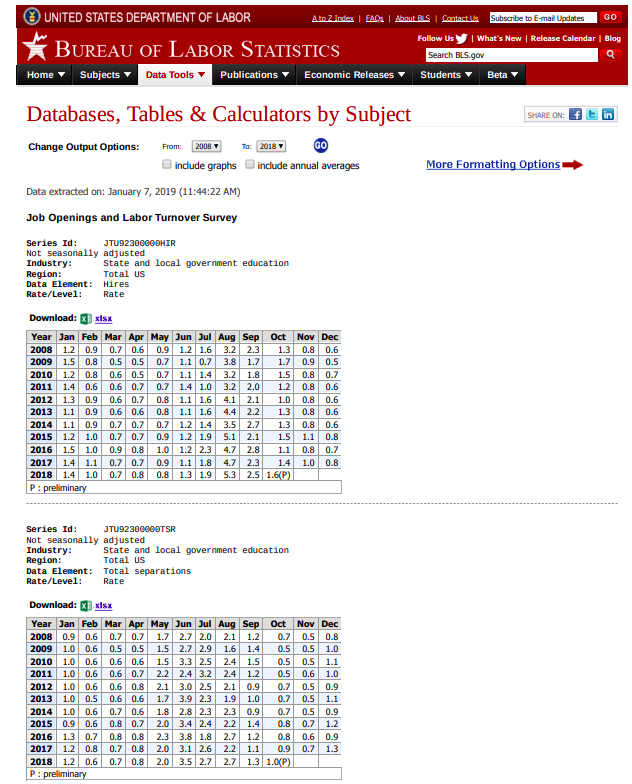

The government statistics cited in the story came from the department’s “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey” — referred to, fittingly, as JOLTS. It is released every month and details the number of hires, fires, resignations — quits, in department parlance — and retirements in every major category of the U.S. economy. What it does not have — and this is specifically noted in its frequently asked questions — is “turnover rates by occupation.”

Neither the U.S. Department of Labor nor the Wall Street Journal knows how many public school teachers are quitting.

What JOLTS does tell us is the quit rate for the 10 million education workers employed by state and local governments, of whom about 5 million are certified teachers, defined broadly. Hundreds of other occupations are also included, such as administrators, accounting and finance specialists, computer and database analysts, psychologists, counselors, social workers, public relations specialists, speech pathologists, security guards, food service workers, landscapers, receptionists, clerks, construction and maintenance workers, vehicle maintenance workers, and other laborers.

While it is possible that teachers are quitting at a record rate, it is also possible they are not, and that the rise in the numbers is due to office workers, custodians, bus drivers, and nurses quitting at an accelerated rate.

Let’s take a closer look at that quit rate. The Journal story does mention that the average public education 0.83 monthly rate is “still well below the rate for American workers overall,” which is 2.31. What the story fails to mention is that it is below the quit rate for every other job category except one — federal employees.

What about the rate of increase? The teacher quit rate hit a record low of 0.48 in 2009, and so it has increased by 73 percent. Alarming, yes? But only if you ignore the rest of the American economy, which had a quit rate of 1.35 in 2009 and so has increased 71 percent.

In the past year, the change in education employee quit rates did not pass the JOLTS “test of significance,” even though those of the private sector as a whole did, as did six individual categories. I searched in vain for a national story about the quit rates in the entertainment industry, one of those singled out as passing the test.

There is another nuance in the JOLTS data. “Quits” include those who left their present job to accept a different job. So if a teacher leaves District A for a higher-paying job in District B, she quits and is counted in the statistics. If we examine quits without examining hires, we get only half the picture.

There is no shortage of teacher-shortage stories in the national press. Is it that difficult to replace quitting teachers? To answer that question, we must include all those teachers who retired and were dismissed in the number of quitters. Fortunately, JOLTS does that for us.

Using the JOLTS database to compare figures, we can compute that the average monthly percentage of public education employees who left their jobs one way or another in the first 10 months of 2018 was 1.65 percent. That was a record high.

Doing the same for the hire rate for the same time frame, we find the figure was 1.73 percent. That also was a record high. We have increased the size of the public education workforce every year for the past five without a headline about teachers entering the profession in droves.

I suppose it is hopeless to swim against the tide of teacher shortage/retention stories. Consider this a final flare fired before I go under.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)