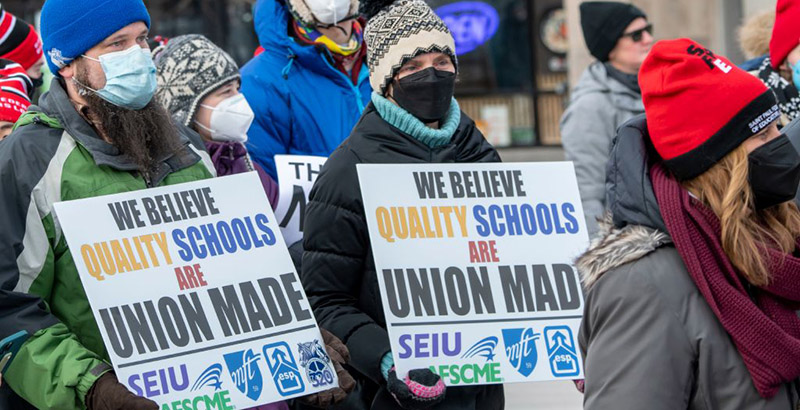

Twin Cities Teachers Vote to Strike — Demand Pay Raises, Protection for Educators of Color as COVID Drives Student Enrollment Down

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Minneapolis and St. Paul school district teachers and classroom aides have voted to authorize their unions to call for strikes. The votes don’t necessarily mean they will walk off the job, as state law calls for a cooling down period of at least 10 days.

Leaders of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers and Educational Support Professionals said more than 90 percent of their members voted, with 97 percent of teachers and 98 percent of classroom aides favoring a strike. Two-thirds of St. Paul Federation of Educators members cast ballots, with 78 percent approving a walkout.

“For decades, we’ve watched as district leaders choose to not invest in our students, our schools,” Minneapolis union President Greta Callahan said in a Friday online news conference. “We’ve also seen those at the very top elected leaders defund our schools. It’s time to make some serious investments.”

Union demands include pay increases, reduced insurance premiums, class size caps, more school psychologists and social workers, and efforts to recruit and retain teachers of color. Administrators in both districts have said declining enrollment and associated decreases in state funding put the cost of meeting the unions’ demands out of reach.

The time is now! @MFT59 teachers and ESPs vote with comfortably over 90% participation, and an astonishing over 97% Yes on authorizing a strike.

— MN Workers United! (@MNWorkersUnited) February 18, 2022

The time is now to invest in the safe and stable school Minneapolis kids deserve. pic.twitter.com/363EyEfqNK

St. Paul teachers went on strike two years ago and narrowly averted a walkout two years before that. Its 2,500 teachers are the best-paid in the state, with an average salary in the 2020-21 school year of $85,457. District officials, who recently announced they would close several schools because of drops in enrollment, have said their hands are tied by a $43 million budget shortfall.

They also say class-size caps in the current contract have been an impediment to increased enrollment. In the 2020-21 school year, St. Paul Public Schools enrolled 35,000 students. District officials project that next year, the number will drop to 32,000.

Minneapolis teachers have not struck since 1970, according to media reports. The district has seen a more dramatic drop in enrollment than St. Paul, and taken fewer steps to adjust. In 2016, it had nearly 35,500 students. This year, enrollment is hovering around 29,000. If Minneapolis’ 2,500 educators do walk out, some big questions will be put to the test.

A year ago, the district and the union began negotiating a contract to cover the 2021-23 school years, with any increases in compensation and benefits applying retroactively to June 2021, when the last contract lapsed. The union’s educational assistant chapter is also negotiating a new contract on the same timeline.

Citing frustration with a lack of progress, district leaders asked state officials in October to appoint a mediator. By law, once mediation begins, sessions are closed to the public and the parties are limited in what they can say. Minneapolis Public Schools officials declined to comment for this story.

The union’s last public offer, issued in early December, demanded a 20 percent increase to the salary schedule for the 2021-22 school year and 5 percent for 2022-23, as well as permanent hikes to pay rates for extra duties and professional development.

According to the district, meeting these demands would cost $45 million in the first year of the contract, which would be paid retroactively, and $65 million the next year. The district has countered with increases totaling $20 million over the two-year contract.

Behind the saber-rattling, the district finds itself at a serious inflection point. The pandemic accelerated a decade of enrollment losses that officials have for years warned must eventually result in a drop in the number of teachers — and possibly schools. Since the start of the 2019-20 academic year, the Minneapolis district has lost more than 12 percent of its students, according to preliminary data.

Last fall, as negotiations were underway, district leaders said they would dedicate nearly half, or $75 million, of Minneapolis’ share of the third round of federal COVID-19 recovery funds to stave off layoffs necessitated by pre-pandemic budget deficits. All told, the district will use $108 million to plug fiscal gaps.

Some school finance experts have warned against using relief dollars to delay painful decisions associated with “right-sizing” shrinking districts, noting that such measures often increase the size of the “fiscal cliff” a school system will face when the money runs out.

At the same time, the district is in the midst of a reorganization intended to stanch the years-long exodus of families of color by redrawing attendance boundaries and making schools more welcoming to Black, Latino, Native American and Southeast Asian students. Without changes to the teacher contract, retaining many of the educators vital to that effort will be unlikely.

Next year, the district will need 135 fewer teachers, according to its financial projections. By fiscal year 2027, it will need 219 less, assuming continued drops in enrollment. State revenue may continue to tick up modestly, but so will the salary schedule that automatically increases teacher pay each year.

Union leaders say their members are overdue for meaningful raises, among other things demanding that 90 percent of the nearly 1,000 classroom aides — whose pay ranges from $15 to $30 an hour — earn a starting salary of $35,000 or more.

District leaders have not said how much wages have increased over the last decade, but according to Minneapolis’ Star Tribune, from 2011 to 2018, instructional salaries went up “dramatically.” During those seven years, administrators told the newspaper, classroom aide wages rose 31 percent.

According to state records, average teacher pay rose from $70,708 in 2019-20 to $71,535 last year. According to the teacher contract, the lowest starting salaries have risen from $37,000 to $44,500, while the highest have fallen from $103,000 to $98,000.

Pay isn’t the only issue. District, union and community organizations are in the fourth year of a conversation about how to diversify the teacher corps. Those discussions have repeatedly deadlocked. By law, teachers who will be laid off must be notified in coming weeks. If the stalemate is not broken within that time, community advocates say, many recently hired educators of color will be let go.

Because new hires are disproportionately teachers of color, historically they have been laid off in large numbers. According to the Advancing Equity Coalition, a consortium of community groups, this is why, despite increases in the number hired, the district had a net gain of just six teachers of color between 2018-19 and 2020-21.

In Minneapolis, 74 percent of white students passed last year’s state reading test, compared with 24 percent of children of color and Indigenous students. Similar disparities are seen in math. Research shows that children who have at least one teacher who looks like them do better academically and socially. Yet some 82 percent of district teachers are white.

Partially in response to a district diversity audit several years ago that showed teachers of color made up 14 percent of Minneapolis’ educator workforce in 2014 and 17 percent in 2018, the district stepped up recruitment among underrepresented demographics. In 2020, 30 percent of new teachers were of color. Yet, 37 percent of teachers of color and Indigenous teachers are probationary, meaning they enjoy little job protection, versus just 23 percent of white teachers.

Because it’s not legal to make layoff decisions based strictly on race, school districts that want to protect their teachers of color have had to come up with mechanisms for modifying educator contracts. Before closing the talks to the public, district administrators and union leaders were unable to come to agreement on which teachers to protect.

According to their proposals, the teacher union wants to extend layoff protection to teachers at the district’s 15 most “racially identifiable” schools — buildings where the percentage of students of color exceeds a certain legal threshold. Citing a desire to have a diverse workforce in all schools, district officials proposed protecting educators who are underrepresented when compared with the demographics of the student body, who are members of the communities surrounding the schools and otherwise have a “cultural or communal affinity” to the building where they work.

As talk of a possible strike began circulating in recent weeks, community activists said they feared the lack of agreement on layoffs would mean fewer teachers of color in classrooms next year.

“We cannot let [the union] use protections for teachers of color as a bargaining chip or leverage with the district,” said Titilayo Bediako, executive director of the nonprofit We Win Institute and a former Minneapolis district teacher. “And that is why an agreement needs to be in place before a strike begins.”

The next mediation session for teachers is scheduled for today. The educational assistants’ unit returns to the bargaining table Feb. 22.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)