For several years, as a volunteer with a group modeled after Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, I served as a mentor to a child who spent her early years in an Atlanta housing project. The young lady was attractive, polite, amiable and, at 12, barely able to read.

You wouldn’t have known that from looking at her grades, though. She received mostly Bs, with a few As and a few Cs sprinkled throughout her report card. It turns out that her teachers rewarded her good conduct with good grades. At her low-performing school, it didn’t seem to matter that she wasn’t actually learning much.

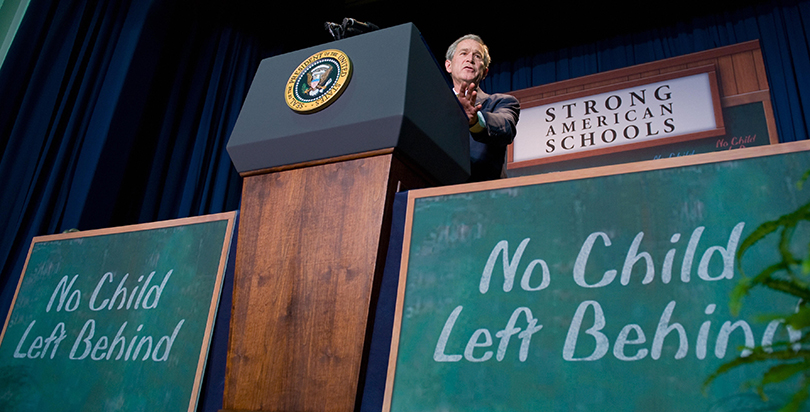

It was precisely this “soft bigotry of low expectations,” as then-President George W. Bush memorably put it, that No Child Left Behind was meant to remedy. And, flawed though the legislation was, it was a decent attempt to ensure that every child — whether rich or poor, black, white or brown— received a high-quality education.

In other words, No Child Left Behind was civil rights legislation, a law designed to close the dismaying achievement gap that separates the educational attainment of black and brown children from their white peers.

But NCLB quickly became unpopular among some teachers and parents because of a strict testing regimen that some experts say distracts from the classroom experience. Too many teachers started to “teach to the test,” they said. And the law’s annual assessment of schools vexed principals, stressed teachers and spawned cheating scandals.

No Child was clearly in need of a 2.0 upgrade. Unfortunately, though, Congressional re-writes (read about the Senate’s latest version of the reauthorization) have dumped its most important provisions, including the tough accountability policies that helped ensure that less-affluent kids are actually being taught.

Without those accountability measures, including federal penalties for failure, public schools will return to a system in which poor kids are too often overlooked, neglected, ignored, passed over and passed on, whether or not they have mastered their grade-level requirements.

Students such as my protégé would continue to get good grades, regardless of their actual academic skills.

National Urban League President Marc Morial says that’s a violation of their civil rights. He has joined several other civil rights leaders in urging Congress to maintain the federal mandates that hold schools accountable for what students actually learn.

“The tests are not perfect, but without tests what do you have?” he asked me. “As much as people may not like testing, it’s the only available way for us to document and to hold schools and school districts accountable. We can’t close the achievement gap unless we know what it is and how big it is.”

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson passed the first law attempting to redress generations of injustice in educational opportunity. The Elementary and Secondary Act, which followed landmark legislation on civil rights, was part of Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” It acknowledged the nation’s ignominious history of denying educational opportunity to black children and listed among its goals closing the achievement gap.

Yet, when Bush set about re-making the law in 2001, the achievement gap remained stubbornly in place. That gap is now finally closing for black children born to affluent and well-educated parents, research shows. Poor kids, however, are still not getting the education they deserve.

And Congress is moving away from its commitment to them. Conservatives are leading a libertarian charge that virtually strips the federal government of its oversight role in elementary and secondary education. Educators and their unions, meanwhile, have successfully campaigned against President Obama’s policy of tying teacher evaluations to students’ test scores. They’ve also persuaded the Senate to strip away federal sanctions for failing schools, arguing that states should have that authority.

But Morial notes that turning all power over to the states to oversee educational outcomes is a recipe for failure, a return to the same system that neglected children of color for generations. “We can’t support the idea that you just turn it over to the states. That’s a state’s rights argument,” he said. (For evidence of the failure of state oversight, look no further than the schools in Ferguson, Mo.)

It’s been more than half a century since the U.S. Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board, struck down a segregated system that kept black children in inferior schools. Since then, much has changed for the better, but poorer students — especially those of color — are still not getting an equal education. And if Congress now refuses to hold schools accountable in its re-write of No Child Left Behind, they have no chance of getting it.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)