Tucker: Time to Cheer – and Double Down on – NOLA’s Ed Breakthrough

This is one in a series of articles covering the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and the rebuilding of New Orleans’ schools. Read all our coverage and essays here – and be sure to watch our three-part documentary series about the past, present and future of New Orleans education.

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc along the Gulf Coast, nearly destroying New Orleans, rebuilding efforts are proceeding slowly but steadily. The Big Easy has restored its tourist economy, reclaimed its place as a haven of fine dining and rebuilt some of its once-uninhabitable neighborhoods.

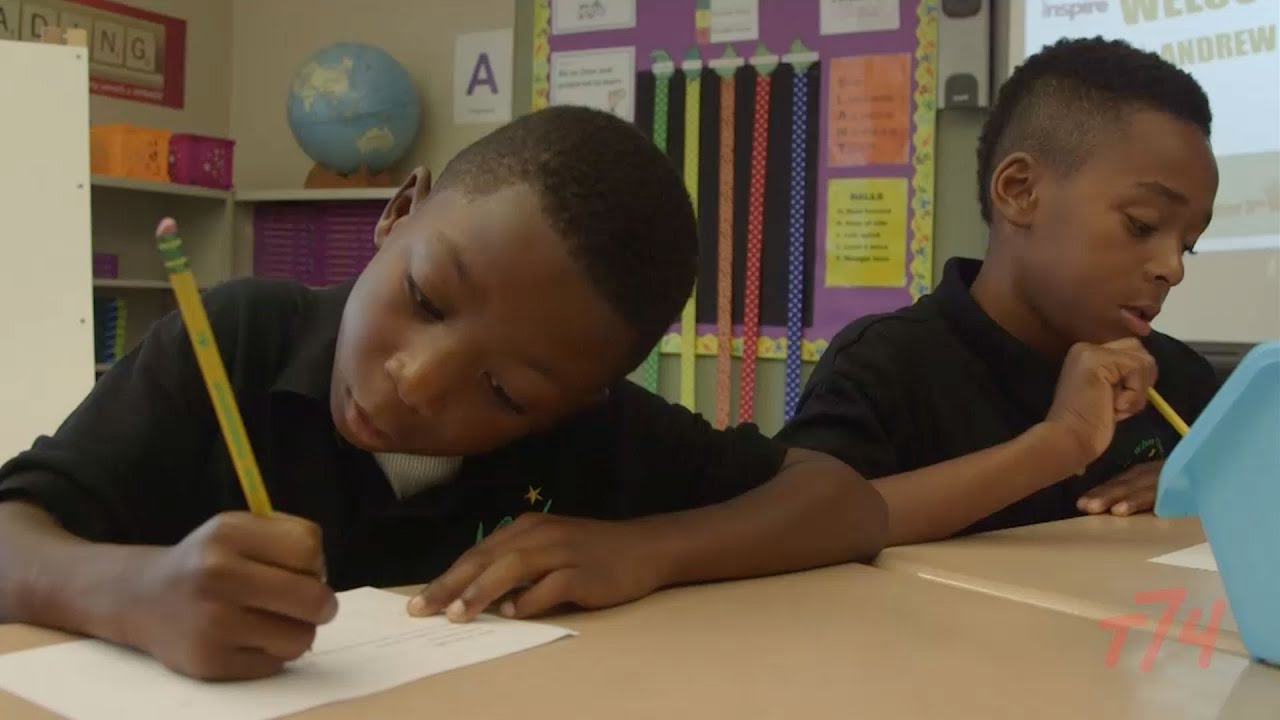

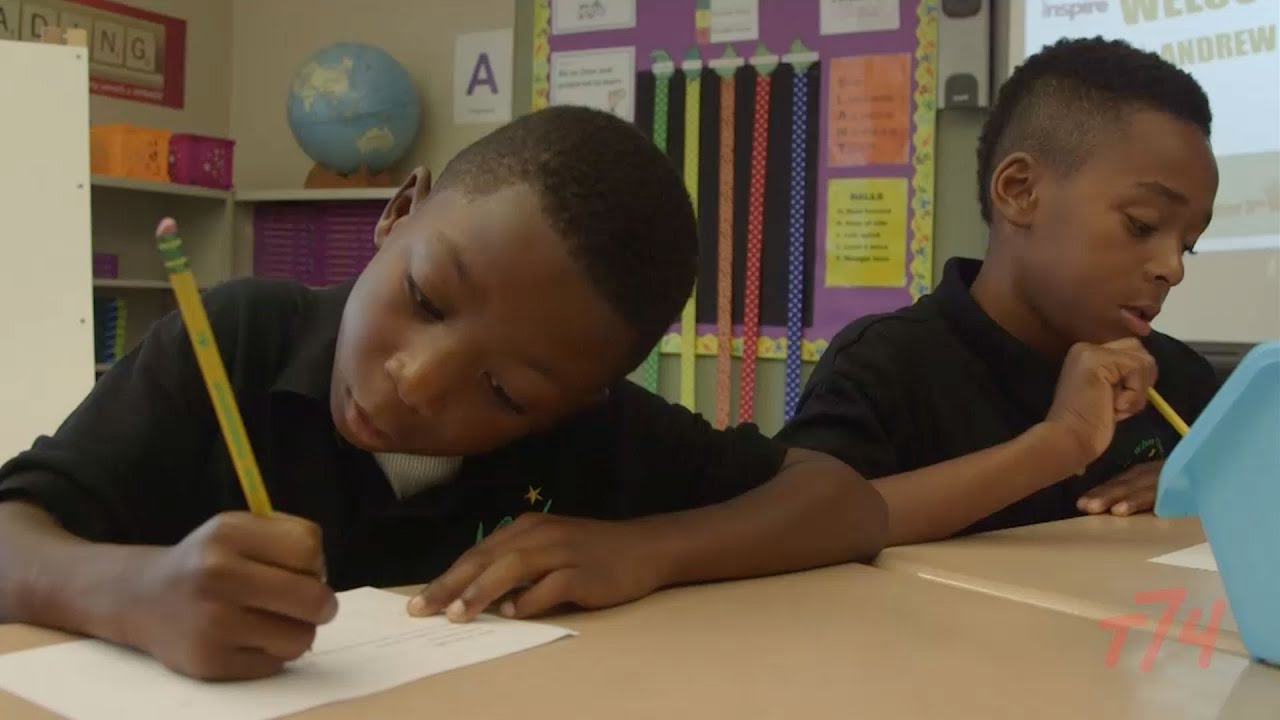

Nowhere is the renewal more evident than in the city’s public schools, which have overturned a failing bureaucracy to emerge as innovative laboratories for learning. Data from several studies show that, since 2005, standardized test scores are up and graduation rates are, too. Tulane University researcher Douglas Harris has found test score gains of 8 to 12 percentage points.

None of the data portray the city’s new schools as a panacea. They have not found a magic formula to close the achievement gap between poor students and their wealthier peers, to grant them the knowledge and sophistication that affluence bestows. Tulane’s highly-respected Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives says the schools have stepped up from “failing to average.”

Still, that’s genuine progress, cause for excitement. You’d think that educators and legislators, parents and activists would join in the celebration — before rejoining the hard work of ensuring every child a good education. Instead, news of the schools’ early successes has been met with recriminations, controversy and dispute.

That’s because nearly all the students who attend public schools — about 93 percent — attend charters run without the oversight of traditional bureaucracies. That’s the highest rate of charter school attendance in the nation. So the success of the Recovery School District has drawn the ire of the anti-charter school crowd — traditionalists who are furious at the suggestion that throwing out the old bureaucracies, and replacing sub-par principals and teachers, might actually work.

Leading the charge against charter schools are teachers’ organizations, including their unions. They are especially chagrined that New Orleans has become a model for other education reformers, fearing that it may inspire similar experiments across the country.

Let’s take a look at New Orleans schools before Hurricane Katrina.

Louisiana has historically languished toward the bottom of the heap in educational achievement — in January, Education Week ranked the state 44th out of 50 —and the Orleans Parish school board operated some of the worst schools in Louisiana.

The schools’ mission is to educate children, not to provide paychecks to adults

Essentially, the city had a two-tier system, with private and parochial schools serving the advantaged and the failing public schools serving the poor. (Even now, about 25 percent of New Orleans’ students attend private or parochial schools, one of the highest rates of non-public school attendance in the nation.) Even working-class families with little money to spare scrimped and saved to send their children to parochial schools.

The local education bureaucracy was corrupt and dysfunctional. Eight superintendents served between 1998 and 2005, lasting, on average, 11 months. The Federal Bureau of Investigation issued indictments against 11 people in the system for financial mismanagement in 2004.

When Hurricane Katrina struck, shutting down essential services, the state of Louisiana took advantage of the tragedy to take over the entire system. Without money to pay teachers, the state laid off more than 7,000 of them en masse and required them to reapply for their jobs. Some were re-hired; many were not.

Those lost jobs are undoubtedly the source of much of the animosity that has greeted the charter schools of the Recovery School District. And it’s understandable. It’s difficult to overestimate the trauma for teachers and principals who lost not only their homes but also their livelihoods.

But the greater injustice would have been to leave New Orleans’ poorest students — its most vulnerable citizens — in schools that weren’t teaching them anything. Without the skills necessary to thrive in a global economy, they would likely have been doomed to lives of poverty. After all, the schools’ mission is to educate children, not to provide paychecks to adults.

Critics also note that the teaching corps is whiter (and younger) than it was before Hurricane Katrina, drawing many of its professionals from non-traditional programs such as Teach for America. With a student body that is about 87 percent black, the Recovery School District employs a teaching force that is about 54 percent black, down from 71 percent before Katrina, according to the Cowen Institute.

The Recovery School District is making an effort, as it should, to hire more black teachers. But those teachers need not come out of the traditional educational bureaucracy and teacher certification programs that have shown themselves incapable of innovation.

Finally, many of those who dispute the successes of the Recovery School District cite its failure to solve all the problems of educational inequity: children continue to struggle with poverty; the drop-out rate is still too high; college entrance scores and college attendance rates remain sub-standard.

All of that’s true.

That’s why education advocates should continue to build on the gains that New Orleans has made over the decade since the storm. There is certainly much more work to be done. But denying the progress that’s already been made is a huge step in the wrong direction — a denial that would doom New Orleans’ poor, black kids.

A 74 Documentary | Part I: Reopening in the Flood Zone

Part II: The Class of 2015

Part III: The Next Generation

Photo by Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)