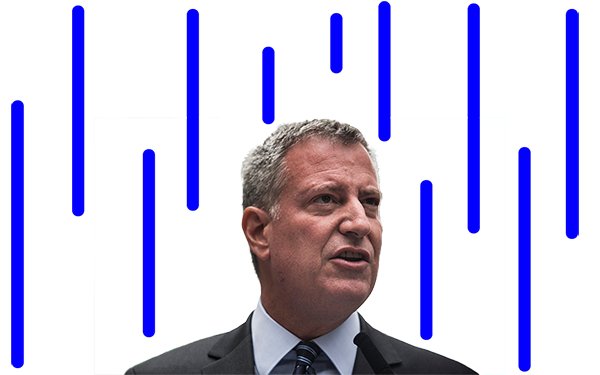

Tucker: De Blasio Wants to be the ‘Education Mayor’ But Leaves Too Many Failure Factories Still in Business

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has said that he wants to be, among other things, the “education mayor.” That’s a laudable goal; he has few more important responsibilities than ensuring that every child gets a high-quality education. And his successful implementation of a universal pre-kindergarten program, despite the doubts of critics, shows a commitment to helping kids get a good start.

But being the “education mayor” — which entails convincing state lawmakers he deserves extended mayoral control over the city’s schools — may require disagreeing with traditional allies, upsetting entrenched interests and even taking positions that the mayor once opposed. Let’s hope his recent decision to close some failing schools shows that he has learned that lesson.

In December, the city’s Department of Education announced that it would shutter three low-performing schools instead of giving them years to improve. With that announcement, de Blasio hinted that he might be heeding critics of his School Renewal Program.

De Blasio had not a word to say about the $400 million program during his Feb. 4 State of the City address. That may be because the latest news about the 94 Renewal schools was that the mayor and Schools Chancellor Carmen Farina had decided to give them three years to meet goals other schools had one year to accomplish. In January, the city’s principals union called the program top heavy, inefficient and a “recipe for disaster.” (See The 74 on Where Have de Blasio’s Grand Education Plans Gone)

The closures are but a small step in the right direction. The three schools, all in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, have fewer than 220 students among them. It may be that they were targeted because of their size, not for poor academic performance.

If de Blasio is to ensure a high-quality education for every child, regardless of his or her background, he needs to set aside the Renewal Program, which will leave students in factories of failure for years.

Earlier this month, it was reported that graduation rates at 10 low-performing high schools in the Renewal program had either not improved or sunk even further. At August Martin High School in Queens, for example, the rate went from 39.2 percent in 2013-14 to 25.9 percent last year, and at the Bronx Leadership Institute, the rate plummeted from 42 percent to 28.6 percent. These schools and others like them remain open.

When he ran for mayor in 2013, De Blasio campaigned as the anti-Bloomberg, promising to overturn many of the policies of his predecessor. That included Mayor Bloomberg’s policy of quickly closing schools that weren’t teaching much of anything. De Blasio and Farina have been outspoken in their criticism of Bloomberg’s approach, vowing that “schools should be run as schools, not corporations.”

OK. But shouldn’t schools be expected to perform their essential mission, which is educating school children? And, if they don’t, shouldn’t they be shuttered so that kids can attend better schools?

A report released in November by the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, a non-partisan think tank at New York University, shows that Bloomberg was right to close low-performing schools. That policy benefitted the middle-school kids who no longer had to attend them.

“Meaningful benefits accrued to the post-closure cohort,” the report states. “These students attended higher-performing high schools . . .This shift in their enrollment options led to improvement in students’ attendance, progress toward graduation, and, ultimately, their graduation rates — with large increases in the share of students earning a Regents diploma.”

The strategy of replacing large failing schools with smaller schools was successful but not a panacea. The three schools that de Blasio has chosen to close were all started during Bloomberg’s administration. (That, too, may have prompted de Blasio to swiftly close them — another sharp stick in his predecessor’s eye.)

But there are no magic bullets in the battle for public education reform. No tool works perfectly, no innovation catapults every student onto the path to success. Still, the report from the Research Alliance shows that, generally speaking, students are better off when they are taken out of bad schools and placed in better ones. Makes sense, doesn’t it?

By contrast, de Blasio and Farina gives New York City’s failing schools a maximum of three years with extra funding to turn around — a goal that some education experts believe is unattainable. Instead, it simply wastes precious years in the academic lives of the students stuck in them.

Closing schools is undoubtedly controversial, even when they haven’t lived up to their mission. Union leaders, principals, and teachers protest. Parents resist. Community activists march and demonstrate.

But the essential job of any school is to give its pupils a high-quality education. If it doesn’t do that, it should be closed — immediately — so those kids can attend a better school. If de Blasio wants to be the “education mayor,” he needs to attend to the kids, not the adults.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)