Tuchman & Pillow: Out-of-School Enrichment Is Critical to Student Success. We Must Close the Access Gap for Black and Latino Kids

This essay previously appeared at The Lens, the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s blog at the University of Washington Bothell. The research discussed in this blog post was taken from Thinking Forward: New Ideas for a New Era of Public Education, released by CRPE in celebration of its 25th anniversary. It shows how ideas from two essays in that volume, Educational Equality in the Future: Risks and Opportunity and Beyond the Bell: Leveraging Community Assets for an Expanded Learning System, play out on the ground in Denver.

We hear a lot about the achievement gap, but people don’t usually talk about the access gap. If they do, they mean access to high-quality schools. But schools aren’t the only thing that students need access to in order to reach their goals. Access to enrichment matters, too.

A new analysis by researchers from the University of Washington eScience Institute, in partnership with CRPE and ReSchool Colorado, shows a recurring trend that students who are black or Hispanic, and those who come from households with lower incomes or less-educated parents, tend to have less access to out-of-school opportunities that might affect their learning.

There are thousands of programs within cities that offer students the chance to learn about topics schools are often unable to teach or can no longer afford to offer. Arts, music, and sports programs enrich learning, promote social-emotional awareness, and may help students build background knowledge. A growing number of studies have found that trips to theaters and museums, learning opportunities during school breaks, and other enrichment programs benefit a wide range of student outcomes. But not every student has the same access to these sorts of opportunities.

This past summer, Sivan worked with five graduate students and two data scientists at the Data Science for Social Good program to analyze ReSchool Colorado’s summer programs website, Blueprint4SummerCO. The website is meant to help families find and enroll in summer activities and programs in Denver, Aurora, and Boulder. We then worked with ReSchool to understand whether the opportunities available to families in Denver were distributed in such a way that families had equal access to them.

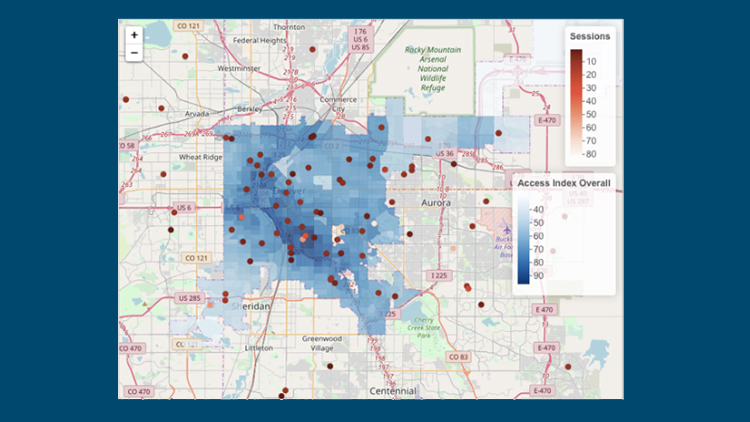

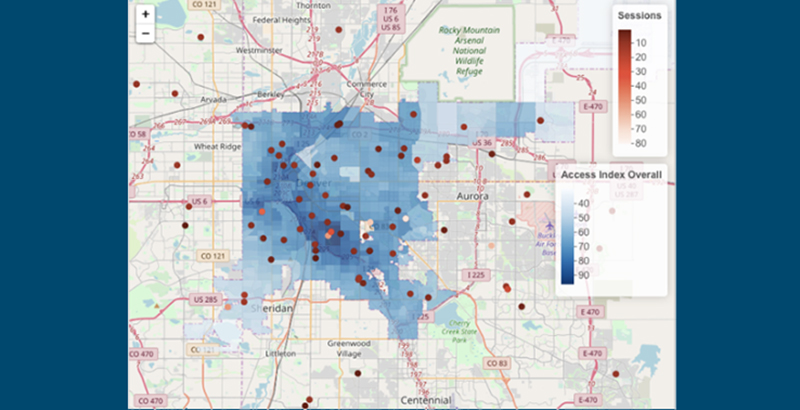

We created an index from 0 to 100 to measure the level of access that a given Census block group has to out-of-school programs. The map below shows that the darkest-blue areas, where access is the highest, run diagonally through Denver where the more affluent and white families live. The lightest-blue areas, somewhat unsurprisingly, are the southwest and northeast corners, where more Hispanic and black families live.

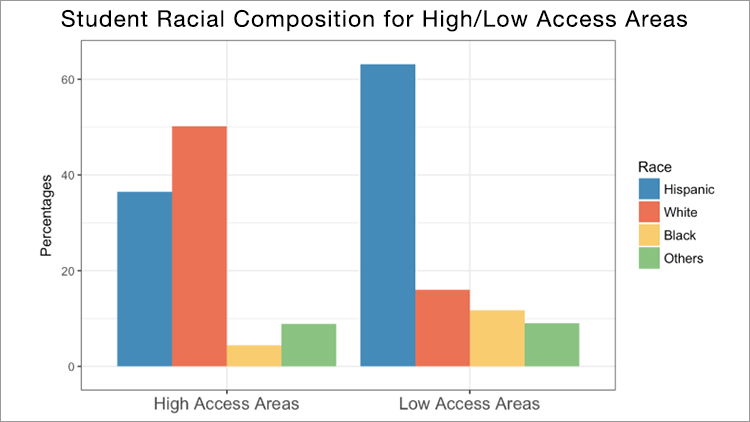

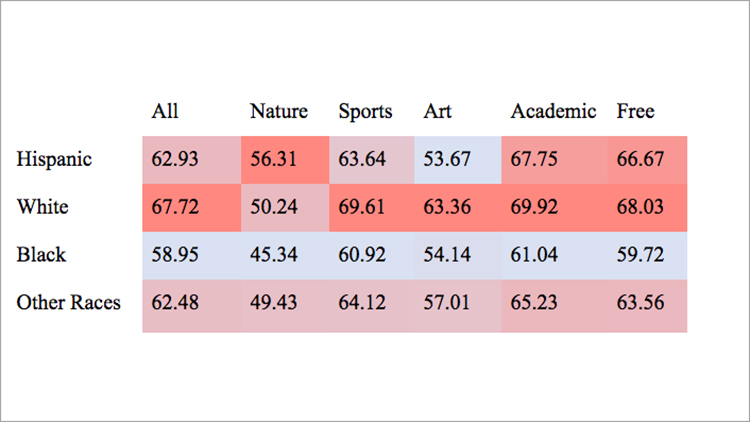

If we look at the differences in access to opportunities by racial group, we see that white families are much more likely to be located in neighborhoods with high access to out-of-school programs, while Hispanic families are far more likely to live in Census block groups that have low access to these same opportunities. (Neighborhoods are composed of Census blocks. We generally choose to utilize neighborhoods rather than Census blocks for their easier interpretation.) When we look numerically at the index scores for each racial group, we see that black families are consistently located in neighborhoods with the lowest access to all types of out-of-school opportunities. Conversely, white families have the highest access to every type of program except for nature programs.

Although these results may be more a consequence of household income, with white families having higher incomes and thus the ability to live closer to the city center where more programs are located, the consequences are still the same. There is a clear gap in the access students have to these important summer enrichment activities that can boost student academic achievement, academic attainment, and social behaviors (such as reduced drug use and pregnancy), increase disadvantaged students’ cultural capital, improve students’ critical thinking, and increase social tolerance. Disadvantaged students or students of color should not be deprived of these positive outcomes, which may actually help reduce the achievement gap.

This research is the first step that cities can take to better understand the enrichment gaps that exist between student groups. The next step is finding solutions to help fill the gaps. In our work, we found that parks, fields, and libraries were all evenly distributed throughout Denver. So why not maximize these existing resources? Cities can build incentives or lower barriers so that private and/or nonprofit programs can operate out of these locations, giving the same access to opportunities for all students. Cities could also consider giving families scholarships that would allow them to pay for enrichment programs for their children. Creative use of public transportation, combined with existing school district transportation resources — particularly during the summer and after school — could be utilized more effectively to support access, as well as when new programs cannot be located in certain neighborhoods.

Closing the enrichment gap will require creative thinking by school and community leaders. The solutions they develop may ultimately help reduce the achievement gap as well.

Sivan Tuchman is a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, where she studies how educators and families experience the implementation of innovative policies and programs in K-12 schools and the systems that support them. Travis Pillow is an education reform chronicler and former editor of redefinED, a website chronicling the new definition of public education in Florida and elsewhere.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)