Trump Towers Over Education: How His Candidacy Is Already Affecting Federal Policy

The brash businessman’s comments seem to force fellow Republicans to respond to some new outlandish statement every day, such as his continued calls to ban Muslims or monitor mosques, or questions on the impartiality of a judge of Mexican heritage.

Although the real estate magnate has mostly avoided impolitic statements concerning America’s schools, Republicans who care about education are hardly protected from Hurricane Donald: the tumult of his candidacy and distant prospect of his presidency already has an impact on party strategy for implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act, the nation’s new K-12 education law.

Think back to November 2015, when Congress approved the law. It was a simpler time — or at least more naïve. Trump was leading in the polls, but it was widely believed he had no chance of winning. A safe establishment choice, like Sen. Marco Rubio or Gov. Jeb Bush, would ultimately emerge as the party’s nominee.

Party leaders believed that if implementation of ESSA under the Obama administration failed to meet conservatives’ hopes, they would have at least a fighting chance of electing a reasonable Republican to steer the law going forward.

Those same Republicans are scrambling to shape the rules for implementing the law, now, despite frequent opposition from Obama Education Secretary John King. Instead of playing ball, King has issued regulations on school accountability and finance that aim to help poor students but also infuriate congressional Republicans. They believe King’s directives violate the law, which is premised on reducing the role of the federal government in education.

(The 74: Under ESSA, Why John King Won’t Go Along to Get Along)

Trying to negotiate with the secretary has come to be seen as a more promising option than waiting to see what 2017 brings, however.

The ESSA timeline is tight: waivers from No Child Left Behind end this summer, with the 2016-17 academic year set to be a sort of a Wild West transition. State plans for ESSA are due by the end of the calendar year; it will be up to the next president to decide if states are following the rules King set.

Practically speaking, there’s little that Republicans can do now to substantially influence the new federal rules. Legislation to overturn agency regulations under the Congressional Review Act has to be signed by the president. Proposals to block Education Department regulations on spending bills historically have gone nowhere.

“The frustration is that we see an administration that doesn’t appear to be reading the plain language of the law, but there’s not much we can do about it,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank. “Besides holding oversight hearings and complaining loudly, I’m not sure what else they can do.”

Petrilli, who counts himself firmly in the “Never Trump” camp, added: “If it seems like some of us on the right are at wit’s end, [it’s because] many of us can’t get ourselves to actually root for Donald Trump, and we are looking at probably four more years of much of the same.”

Neither of the likely outcomes of the presidential election are happy ones for conservatives in the education space.

Take the more likely first. Hillary Clinton has decades of experience in government. Her staff of hundreds has scores of experienced policy hands, and continuity in party leadership could convince some Obama Education Department staffers to stay on under her leadership. Big ideological departures from the rules King set are unlikely.

A Clinton victory also imperils Republican control of the Senate. Half a dozen GOP seats are considered tossups or likely to flip to Democrats, with perhaps another six seats in danger if November becomes a wave election. By contrast, Democrats currently hold only one tossup seat. With a Democratic vice president casting a potential tie-breaking vote in the Senate, the party would need to pick up just five additional seats to retake the majority.

Loss of the Senate would mean that Sen. Lamar Alexander, the Republican agenda-setter on education, would be unseated as chairman of the education committee — the venue for the most public charges against the Department of Education. It would also further constrain opportunities to clamp down on regulations through other legislation.

It’s still difficult to see how Trump would be better on education than Clinton for Republicans.

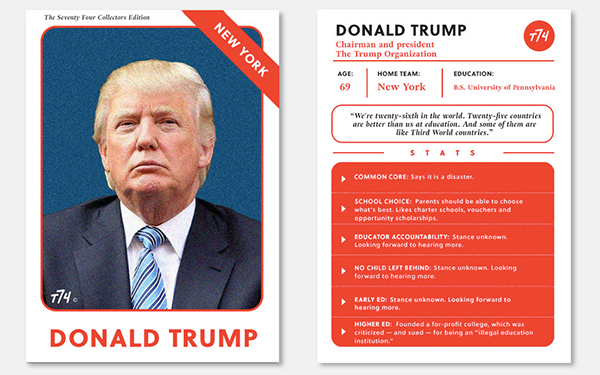

First, there’s the never-ending mystery of what, if anything, he believes about education. He said he’d close the Education Department, but only in the context of emphasizing his opposition to the Common Core. There’s no guarantee that he’d be committed to a smaller federal footprint in American schools or whether he considers education a priority at all.

(The 74: Who’s Advising Donald Trump on Education Anyway? Is Anyone?)

Then there’s the challenge of having to staff a federal bureaucracy basically from scratch (at the same time he is staffing every other government agency) — making it unlikely that a Trump Education Department would be up and running in time to review states’ implementation plans.

Even now, one year after his announcement and as the general election begins to move forward, Trump has just 69 people on staff. Clinton has close to 700, according to federal campaign finance documents.

Petrilli, who was among the first appointees in the George W. Bush education department, wasn’t brought on board until April 2001. There wasn’t a full team in place until late summer or early fall of that year, he said.

A Trump administration – hampered by what D.C. insiders see as a general shortage of Republicans policy talent and by distaste for the candidate – could take even longer, maybe up to a year, Petrilli predicted.

“There’s just no way that there would be a team in place ready to do that kind of work in a Trump administration,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)