Analysis: How Bad Are the Nation’s Teacher Shortages? With All the Conflicting and Unreliable Data Out There, We Don’t Really Know

For decades, talk of a looming teacher shortage crisis has caused anxiety in education policy and practice circles. A 1984 report warned that “shortages of qualified teachers in subjects such as mathematics and science are expected to grow into a more generalized teacher shortage.” A 1999 report predicted the need for an outsized number of new teachers. Most recently, a 2016 report suggested there would soon be a national teacher shortage crisis.

But a generic, national teacher shortage has yet to materialize. The biggest issue districts face in staffing schools is not the lack of certified teachers overall but a chronic and perpetual misalignment of teacher supply and demand. Across 50 states and the District of Columbia, six territories and more than 13,000 distinct districts, there are unique teacher shortages in specific subject areas, school types, and geographies. These specific shortages have real impact on schools, students, and communities.

A gap of one teacher in a school means diminished opportunities for students. And, like many challenges in public education, the pain of teacher shortages is not distributed equitably: The communities that suffer the most from teacher shortages are often low-income and under-resourced.

Proposing broad solutions to “fix” teacher shortages that do not target the specific needs of states, districts, and schools and the individualized contexts in which they operate does a disservice to the communities that are most impacted.

To get a clearer picture of trends in teacher subject-area shortages across the country, Kaitlin Pennington McVey and I analyzed national data on teacher shortage areas submitted by states and territories to the U.S. Department of Education. Our findings confirm what other analyses have found to be true about subject areas that most states struggle to fill with qualified teachers. But it also shows that there is great variation among states on the teachers they need most.

For example, we found that a large proportion of states report subject-area shortages in special education, mathematics, science, foreign languages, and English as a Second Language. However, when we dove deeper, we found that states experience varying extents of those shortages; while many reported special education as a shortage area for 16 of the 20 years of our analysis, states such as Oklahoma, Montana, South Dakota, and Vermont experienced the same shortage for less than eight years.

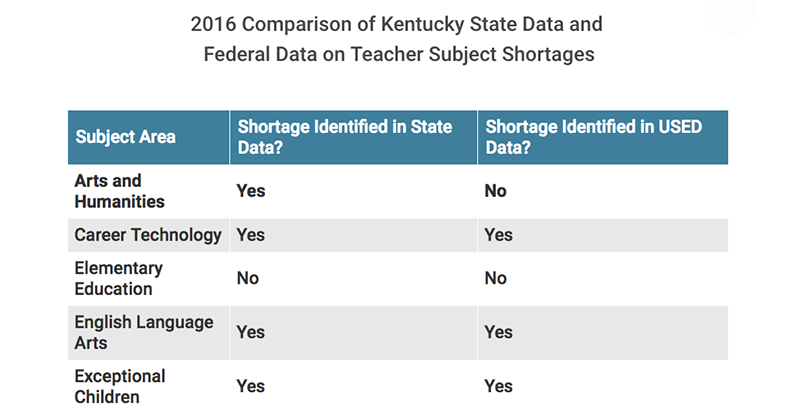

Out of curiosity, we also compared data a few states submitted to the federal government with the data posted on their websites and found a troubling lack of consistency. The first big problem is that shortages reported by states do not always match shortages reported by the feds. For example, Maryland’s 2016 Teacher Staffing Report did not report health and physical education and middle school teachers as shortages, but the feds indicated these subjects as shortages. Similarly, federal data did not report early childhood and elementary school teachers as shortages, yet Maryland indicated them as shortages. In Kentucky, only eight of the 13 subject-area shortages in the federal data matched the state data in 2016.

The way subject-area shortages are categorized by individual states is another mismatch. For instance, Iowa listed more than a dozen categories for special education (e.g., early childhood special education, mental disabilities, behavior disorders) while Hawaii only had one label. As a result, it becomes difficult to make cross-state comparisons and begin developing solutions for shortages beyond the state level. How can we know what types of special education teachers are needed if states don’t even record that information?

We aren’t the first researchers to raise this issue. Dan Goldhaber and Roddy Theobald previously discussed the insufficiencies of national teacher supply-and demand data. Similarly, our colleague Chad Aldeman has highlighted problematic discrepancies in federal data on teacher retention.

State or federal policy can never fully address teacher shortages if we lack consistent and accurate data about the actual challenges. Our analysis indicates that subject areas with teacher shortages vary significantly by state and time period, even among the top shortage areas. But there are also very real chronic shortages — in some states, lasting as much as 20 years — that yet have been unresolved because poor data has led to ineffective policies. We still need more coherent, streamlined processes among local, state, and federal data systems in order to have clearer information about teacher shortages. In the meantime, without better data, we are wasting time and resources developing misdirected policies that may further hurt the teaching workforce in the long run.

Justin Trinidad is an analyst with Bellwether Education Partners on the Policy and Evaluation team. Bellwether was co-founded by Andrew Rotherham, who sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)