Trailblazing Leader Was Hired to Fix Colorado Springs Schools. Will Doubling Down on His Reforms Avert COVID Classroom Crisis?

By Beth Hawkins | August 6, 2021

On Jan. 27, 2021, Superintendent Michael Thomas notified the staff of Colorado Springs’ Mitchell High School that all of them would be released from their positions at the end of the academic year.

They were free to reapply, but major changes were in store. The teachers, classroom aides, custodians and others who wanted to come back in August should be prepared to implement an ambitious plan to increase student achievement.

Mitchell had been among the state’s lowest-performing schools for at least 15 years, during which time it saw precipitous enrollment declines.

Built for 1,700 students, the school’s population dipped to fewer than 1,200 by 2020, while its poverty rate rose from 45 to 78 percent and academic achievement dropped.

It was exactly the challenge Thomas had been tasked with addressing in 2018, when he was recruited by Colorado Springs School District 11 to helm an ambitious effort to improve the quality of its schools. He started by asking for data on how students were doing — and was astonished to learn that the district used only aggregated averages of all students, rather than specific information about different subgroups.

As soon as the information was broken out by race, disability, English learner status and poverty, disparities became immediately apparent. And as Thomas identified and called out inequities that were holding students back, he got anonymous hate mail: “Die” — followed by the N-word.

It wasn’t the first time he had been the target of the slur.

Thomas grew up in Minnesota’s Twin Cities with a Black father, a white mother and frequent opportunities to observe people’s reactions to their skin colors. Strangers would stop his mother in the grocery store to ask where he had been adopted from.

“Even as a child,” he wrote in a doctoral dissertation on the experiences of Black male school administrators, “I could understand the underlying question really being asked.”

In sixth grade, a teacher hurled a racial epithet at him, along with a damning prediction: “You will never amount to shit!”

One night, when Thomas was 18, he and two friends were pulled over by police in an overwhelmingly white St. Paul suburb. The officers grilled them about what they were doing there. “I didn’t have a busted taillight, I wasn’t speeding, nothing,” Thomas remembers now, more than 30 years later. “Just, ‘Get the hell out of Woodbury.’”

When George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer, Thomas recognized the intersection where Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck. A thousand miles away, the superintendent of Colorado Springs School District 11 felt the brutality of the moment in the pit of his stomach.

“I was terrified, watching what happened to George Floyd,” Thomas says. “I am George Floyd. I just happened to live to tell about it.”

After Floyd’s murder, Thomas wrote an open letter to his Colorado Springs community describing his experience being pulled over and explaining its significance to the work he was leading in the school system. The missive was picked up by news media, which pushed it out to a national audience. Soon after, an email appeared in his inbox from the Woodbury, Minnesota, police department. It was from the police chief, who guessed he had been a rookie cop when Thomas had been stopped as a teenager. The chief couldn’t make up for what had happened, but he wanted to offer an apology.

“That brought some sort of closure to a narrative I’ve had to carry,” Thomas says. “For 30 years, I held that in silence. I was held hostage by that narrative.”

When he took the Colorado Springs job, Thomas recalls, he had told school board members that any district turnaround plan would necessarily address racial disparities — no matter how uncomfortable that conversation might make people. Having called out racism as part of a school reboot as a principal in a Minneapolis suburb more than a decade earlier, he knew that in addition to the board’s backing, he would need community buy-in.

A few months into the job, Thomas and his team started holding meetings throughout the city to solicit residents’ wish lists for their schools. People showed up — and spoke up. Much of what they said was deceptively simple: Families wanted good, welcoming schools in their neighborhoods.

“It was amazing,” he says. “When you just simply ask, ‘In our community, what are your values? What do you want to see in schools?’ Guess what — they actually told [us] something. I say that snarkily, because what I’m sharing isn’t anything really profound. But it really helped our community understand we are going to do this journey together.”

Thomas says the meetings sent a signal about his desire to listen to families, which he credits with a 40 percent drop in projected enrollment losses during his first year and a half on the job. But then the pandemic struck. As it did throughout the country, COVID-19 drove enrollment down, with 2,155 fewer students in District 11 schools in the 2020-21 academic year than the year before. As schools were forced to close, Thomas realized he needed to turn again to the broader community to make sure the district’s COVID response was driven by public and family feedback.

In May 2020, Thomas asked the school board to vote, essentially, on the commitment it had made by hiring him. Specifically, he wanted District 11 to enact a policy ensuring he could deploy resources — money, teaching talent, time and access to the district’s best academic offerings — according to equity. The board agreed.

Devices, hotspots, uncertainty about in-person classes: In COVID’s early months, District 11 had the same immediate issues as other school systems. But as the 2020-21 school year got underway, Thomas only reaffirmed his conviction that the pandemic was adding urgency to the changes he had begun making before the crisis began.

And so, with the pandemic just beginning to retreat, Thomas announced he would not put Mitchell High School’s reboot on hold. “Mitchell is full of the brilliant leaders of tomorrow,” he says. “We need to find out what we need to do differently to ensure that we [prepare] them [for] whatever that success means later on in their life.”

The change, he says, needs to far outlast the pandemic recovery.

“You know, I will come and go. But these communities that we’re serving, they’re here forever and for generations to come.”

‘It was a gut punch’

When Thomas announced that teachers would need to apply to stay at Mitchell High School, staff expressed surprise. Colorado law gives low-performing schools five years to improve or face a state-imposed turnaround. But because of the pandemic, no state standardized tests had been given in spring 2020, so the district could, in theory, get an extension. Many assumed Mitchell had more time.

But Thomas and the school board believed running out the clock would be a disservice. If anything, an intensive effort to improve the school was more urgent than ever. COVID-19 had only deepened the inequities Mitchell’s students confront — and cast the disparities in stark relief.

District 11 is one of 17 in the Colorado Springs metropolitan area. On the whole, the community is wealthy, but as the school system that serves the city’s urban core, District 11 is not. More than half the students are economically disadvantaged, and almost half are nonwhite.

One of four district high schools, Mitchell is located in the poorest, southeastern quadrant, where families were much more likely to experience the pandemic’s negative economic, health and academic impacts than their affluent neighbors. It is the only District 11 high school where the poverty rate is higher than district averages and the only one on the state’s list of chronically underperforming schools.

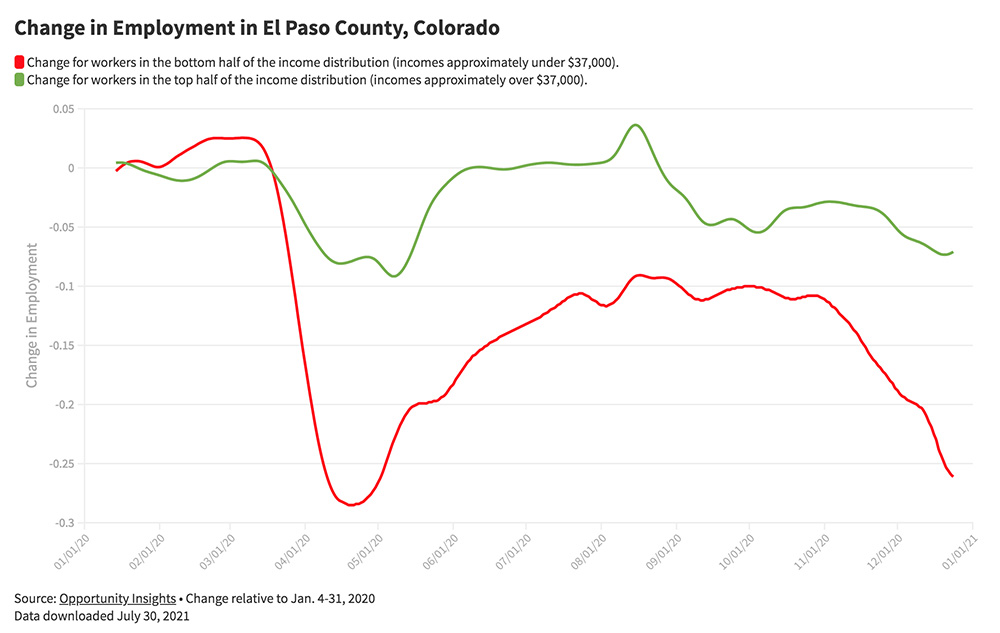

When COVID struck, many white-collar residents of El Paso County, where Colorado Springs is located, were able to work from home. In fact, on Jan. 27, the day Thomas announced Mitchell’s reorganization, employment among county residents earning $60,000 or more was up 1.3 percent over January 2020. Those wealthy households kept spending — but not on meals prepared by line cooks, rides with Uber drivers or housecleaner visits that kept their lower-income neighbors employed.

As a consequence, revenue at the small businesses that the city’s lowest-income residents had relied on for work was down 29 percent over the previous year. Employment dropped 26 percent among those earning less than the median wage of $37,000.

Similar disparities were seen throughout the country.

When the pandemic recession struck, economists John Friedman and Raj Chetty realized it looked different from previous downturns. While even small changes in the way money changes hands create ripples, COVID was a shockwave. The co-founders of Opportunity Insights — a team at Harvard University that researches income inequality and education’s potential to lift children out of poverty — persuaded credit card companies, payroll processors and other businesses that track money as it moves through the economy in real time to turn over what are essentially trade secrets. Using that information, the researchers built a nationwide online pandemic tracker capable of providing a down-to-the-day snapshot of who is spending and who is struggling, by income level, city, state and county and, in some instances, by zip code.

The data quickly revealed stunning implications on virtually every front.

Rather than a typical recession’s V shape, in which people across the socioeconomic spectrum experience both the downturn and the subsequent recovery together, the economists saw a K. Affluent Americans at the top of the K bounced back right away — much more quickly than in a typical recession. But their new spending patterns crippled the businesses that supported their lower-income neighbors; those impoverished families on the bottom continue to struggle disproportionately on every front, beset by challenges long proven to be detrimental to children’s ability to learn in school.

(Friedman and Chetty update the tracker as the underlying information changes. The data in this story was downloaded June 29, 2021.)

Researchers, Friedman told The 74, fear the resulting losses — of jobs, of loved ones to COVID, of mental health supports and reliable food supplies — may have even more devastating impacts for children that schools were already failing to serve, with education’s potential for lifting a family out of poverty moving further out of reach.

The Opportunity Insights tracker contains one academic dataset: student participation and progress on the math app Zearn, which one-fourth of the nation’s K-5 students have access to. Immediately after schools closed, use of the app among low-income students “completely dropped off,” notes Zearn CEO Shalinee Sharma. As they started logging on again, a yawning gap became apparent. A year into the pandemic, these students’ progress was behind where it should have been, while their wealthier peers were ahead 28 percent.

New studies by McKinsey & Co. and the nonprofit assessment concern NWEA found wide disparities between white/affluent students and their low-income peers/children of color. Depending on grade and subject, low-income students ended the 2020-21 school year with up to seven months of unfinished learning.

WATCH: Beth Hawkins details her latest investigation into COVID’s K-shaped recession and how the fallout will challenge America’s schools

As Mitchell proved, in District 11, these disparities were already front and center when COVID hit. When the school board hired Thomas in July 2018, it gave him two priorities: stanch enrollment losses of 700 to 1,000 students a year and make schools more culturally responsive to the rapidly diversifying community. He saw the issues as interrelated: “I thought if we can address these simultaneously, they would take care of each other.”

As he went to work, Thomas found a host of practices he thought needed to change, starting with making decisions based on that aggregate data he found when he arrived.

For example, the data showed that while whites comprise half of District 11 students, they make up 72 percent of those enrolled in gifted and talented programs. The programs are not located in the city’s southeastern quadrant, and the district did not offer transportation to them.

“It was a gut punch. The most damning data was not data showing the disparities and the disproportionality … [it] was the perception data that we collected.” —Alexis Knox-Miller, district director of equity and inclusion

“If we are identifying students who are eligible, we need to make sure that they have access to this program,” says Thomas. “Otherwise, we are intentionally underserving gifted students … we’re punishing the kids for not having transportation. Absolutely ridiculous.”

Similarly, when he dug into the budget, Thomas learned that although four-fifths of Mitchell’s students qualify for free or reduced-price meals, the school didn’t get any federal Title I funds, which are intended to help children living in poverty. When he asked why, he was told that historically, the district had chosen not to send the money to high schools.

“We named the elephants in the room,” he says. “And people were uncomfortable. Because we’ve never had that kind of public conversation.”

Citing the community’s previous feedback, Thomas asked the school board in May 2020 to approve an equity policy and appointed a deputy to oversee its implementation. Her first task was to hire the American Institutes for Research to audit District 11.

The results showed a belief gap underlying the achievement gap, says Alexis Knox-Miller, now director of equity and inclusion: “It was a gut punch. The most damning data was not data showing the disparities and the disproportionality — which is horrible. The most damning data for me was the perception data that we collected.”

On a survey of district teachers, 80 percent of whom are white, researchers found that those who work in the city’s southeastern quadrant, and in schools with concentrations of disadvantaged children, were much more likely to hold negative impressions of their students and families than educators in other schools. Teacher bias, the researchers noted, can translate to harsh, disproportionate discipline, reduced access to challenging classes and wider achievement gaps.

Teachers at schools with the most students of color, for example, were almost 17 percent less likely to agree that parents and guardians do their best to help children learn, while those in the schools with the most students receiving special education services were 11 percent less likely to agree.

Teachers in schools with the most English learners agreed 12 percent less that parents responded to teachers’ suggestions for supporting students. “Significant majorities” of teachers in the more challenged schools, the auditors wrote, did not expect their students to go to college — or to plan to.

Eighteen percent of teachers in southeast schools were rated highly effective, compared with 31 percent in other schools. The disparity was even greater in schools with large numbers of students with disabilities. Concentrations of student poverty correlated to lower teacher pay, with salaries lowest at Mitchell.

The audit also found academic disparities within some of the district’s wealthiest schools. “If you look at Greatschools.org, they’re amazing, right?” says Knox-Miller. “But they have some of the largest gaps between our subpopulations and white students.”

A head start on recovery

Just weeks into the pandemic, it became apparent that COVID-driven school shutdowns would only widen those gaps. Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes estimates that in 19 states in spring 2020, the most challenged students lost up to an entire academic year in reading, and more in math. While other research found better student progress in the 2020-21 school year, children of color, low-income students, children with disabilities and English learners have experienced significant learning losses.

Accordingly, much of the $130 billion in federal relief funding for schools approved by Congress in March is going to schools that serve large numbers of disadvantaged students. The U.S. Education Department has urged schools to spend the money on “evidence-based” interventions to help students recover from both academic losses and the trauma and mental health problems caused by the pandemic. But state and district plans are uneven.

District 11 will provide summer programs, assess students individually to gauge where they are academically and emotionally, and employ a host of other measures recommended by experts as schools prepare to welcome students back full time and in person. But beyond those short-term recovery strategies, the school system has seized the moment to accelerate existing plans to address longstanding inequities.

Alex Carter is vice president of the Colorado Education Initiative, which partners with state education officials and school leaders to push for better outcomes for students. Because District 11 has spent so much time talking to the public about their wish list for schools, it has a head start planning how it will spend its recovery money, he says.

“You saw this big chasm. Some kids have all these fun things to do and some get workbooks.” —Karol Gates, district director of curriculum and instruction

Recognizing that digital learning worked better for some students and that many families are still wary of COVID, the district is launching an online-only K-8 academy in August that is open to any student in the state. Under the equity policy, every school will have the same classroom materials — high-quality ones, backed by research — and teachers will get continuous training and feedback on their use. As a result, in terms of lessons taught, it won’t matter whether students start school online or in person, and it will be less disruptive if they have to move in and out of distance learning.

The devices, digital platforms, and student and teacher portals the district used for remote schooling will remain in place, serving as dashboards where educators and parents can see real-time data on student progress. Teachers can identify which skills individual students struggle with — especially important as children recover from the pandemic.

In many cases, the new, online data system will replace ancient paper binders, says Karol Gates, whom Thomas persuaded to leave her job as head of the Colorado Department of Education’s standards and instructional support team to become District 11’s first director of curriculum and instruction. When Gates arrived in Colorado Springs, the district had plenty of proven curriculum and other top-flight classroom materials — including Zearn, the math app whose data is featured in the Opportunity Insights tracker. But there was no guarantee teachers were using them, much less effectively.

“You saw this big chasm,” says Gates. “Some kids have all these fun things to do and some get workbooks.”

Ensuring that all students have effective materials and quality instruction requires a systems change, she says. When a district buys a curriculum, the vendor often provides one round of staff training, which Gates says is nowhere near adequate. Teachers need ongoing coaching in their own classrooms, schools need in-house expertise and district staff need to help principals whose educators are struggling learn from more successful colleagues.

In the past, principals and teachers often operated in a vacuum, says Thomas. “We at the district level created the Mitchell that we are trying to address today,” he says. “And it didn’t happen overnight.”

Other changes in the offing are designed to make school buildings more inviting — “families shop with their eyes,” says Thomas — and to create the services that now draw parents to other districts under open enrollment. Before COVID, Thomas implemented before- and after-school activities at two elementary schools facing competition from a new charter school. To accommodate working parents, the building will be open from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.

This fall, there will be increased transportation to sought-after Montessori programs and a new dual-language immersion school — something members of the district’s booming Latino population told Thomas they wanted.

“We just got the largest single investment in education in history, and we have three years to spend the money,” says Carter. “The community in three years is going to say, ‘What happened to all that money?’”

“If we can’t answer, we should never ask for full funding again,” he adds. “If we can, we should say, ‘Hey, look what we can do when we’re funded.’”

Building trust and listening

One casualty of the pandemic is trust between disadvantaged families and school systems — already badly strained by historical disparities. Black and Latino households have been especially reluctant to send their children back to traditional in-person classes, with record numbers homeschooling, setting up learning pods and making other arrangements instead.

Yet, of 106 large, urban school districts tracked by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, just one-third mention racial equity in their reopening plans, and just 16 describe what they will do about the issue. It’s an oversight that could prove devastating, says Robin Lake, the center’s executive director.

“Now is the time to think how do we build something back better than it was,” she says. “Normal wasn’t working for too many kids.”

Acknowledging the pandemic’s traumas and strategizing about catching kids up are clearly priorities, she says, but districts shouldn’t stop there. “We should be thinking about this deeply and strategically, not just as an add-on,” says Lake. “The big payoff will come if we can move things forward in new ways, thinking about new strategies for individualizing instruction, for getting students the support they need to engage.”

If the inequities of the past are allowed to persist, she and Thomas agree, the most disadvantaged families may not come back. To that end, late last year Thomas again worked to engage the community, inviting leaders, educators and students to participate in a series of Facebook Live discussions under the name “Beyond the Mask: A Trust Building and Listening Tour.”

Each month had a different specific topic, but the overall theme was the same. If the pandemic presented an opportunity to make big changes, what did the community want its schools to look like? The events proved more successful than anyone dared hope, to judge by both digital attendance and feedback gathered.

“I was surprised,” says Thomas. “We would have maybe about 100 or so people that would stream live, but the hit rates of watching it on Facebook afterwards were up to 1,000, 1,500 hits certain months.”

He is determined to build on that momentum. The district is one of 10 school systems that joined a Colorado Education Initiative effort to plan for reopening schools post-COVID. Each student will have a re-entry plan, but beyond that, the district is betting on “doubling down on partnering with families” — in particular, marginalized ones. Door-knocking, a strategy initially envisioned for re-engaging the Mitchell community, is a centerpiece.

Throughout the pandemic, Thomas continued to meet — albeit online — with 20 high schoolers who make up District 11’s student cabinet, a group of kids whose opinions have informed the changes in the works. Like the families who turned out for the community meetings he held while drawing up the equity policy, he says, the students are explicit about what they need.

For example, the cabinet members told Thomas they struggled to get through “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the traditional anchor to lessons about racism in many U.S. classrooms. More relevant, they said, was Angie Thomas’s “The Hate U Give,” a novel narrated by a Black girl who is the only witness to her friend’s shooting by a police officer.

“I think that’s a great example of our students saying, ‘We want something more,’” Thomas says. “Districts across the country need to be open to hearing from our students, our families and communities about what’s meaningful for them, what will allow their students to plug deeply into that learning.”

Thomas is cognizant of the size of the shift he’s asking people to make, but he believes it has the power to spark radical transformation. “Are we as adults really hearing what our students are telling us?” he asks. “We need to adjust our hearing frequency, because the answers are right beneath our noses.

“We need to honor that and actually empower them to find that voice. Because it’s that voice that’s going to lead this country. It’s that voice that’s going to solve some of the challenges our country is grappling with right now.”

This article is part of a series examining COVID’s K-shaped recession and what it means for America’s schools. Read the full series here.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Lead image: Colorado Springs School District 11

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter