Traditional University Teacher Ed Programs Face Enrollment Declines, Staff Cuts

As higher ed enrollment lags, colleges try to make teacher preparation more enticing, sustainable to ward off local shortages

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The pandemic has exacerbated a troubling national trend: Fewer potential teachers are entering the profession.

Nearly every state lost a large proportion of teaching candidates between 2010 and 2018, according to a Center for American Progress report — and the pandemic has further strained traditional colleges and universities programs, many of which face declining enrollment and were forced to recently cut staff.

Programs like the University of Michigan’s Masters of Teaching are feeling the effects. Their middle and high school cohort is down to about 28 students for the Fall 2022 semester from the usual 45. In Oklahoma, which had over 80% fewer prospective teachers enrolled in 2018, Oklahoma City University will end its elementary teacher preparation after its final three students graduate.

“We have had basically at least an orange flag that’s been waving for the past 10 — and in urban and rural areas, well over 20 years — to say we’re not doing enough to recruit teachers,” said Kendra Hearn, associate dean for educator preparation programs at the University of Michigan. “…Everything has just been exacerbated by COVID.”

Experts believe a combination of economic and social factors are contributing to the decline: High stress working conditions, restrictions and political influence on what can be taught and low wages. In some parts of the country, the acute teacher shortage has been in part attributed to too few teaching candidates in the pipeline. Declining community college enrollment and transfer rates, a common pathway for low-income, Black and brown teachers, have also affected pipelines.

The storm has given rise to many alternative preparation programs — run by nonprofit and for-profit organizations, sometimes in collaboration with universities — that are typically less costly and lengthy.

Simultaneously, public perception of teachers during the pandemic have been overwhelmingly negative, intensifying disinterest in the profession.

“Unfortunately, we had a very narrow window of public understanding of teacher’s work that closed rather quickly after the COVID realities started to become more commonplace,” Jacqueline Rodriguez, vice president of research for the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, told The 74. “So there was a groundswell of interest and support and empathy for teachers’ work. And then that faded rather quickly.”

Carole Basile, dean of Arizona State University’s teacher’s college, agrees, observing the emotional toll of the current climate is steep. She believes it will take much more than recruitment efforts to bolster pipelines and make the profession desirable and sustainable. It may also take a cultural shift in how Americans see and invest in public education.

“We can’t keep preparing them, even if we change our preparation program, to be more flexible and accessible if we don’t also help schools to change to keep them,” said Basile. “It’s a pipeline issue, but then it’s also ‘we’ve got to change schools.’ It’s not okay that teachers sit in their cars crying in October.”

The enrollment lags are impacting historically hard-to-staff subject areas in particular: Interest in special education, STEM and foreign language is dramatically declining. Over the last decade, degrees and certifications conferred in each area are down by 4%, 27% and 44% respectively, adding to concerns about localized teacher shortages.

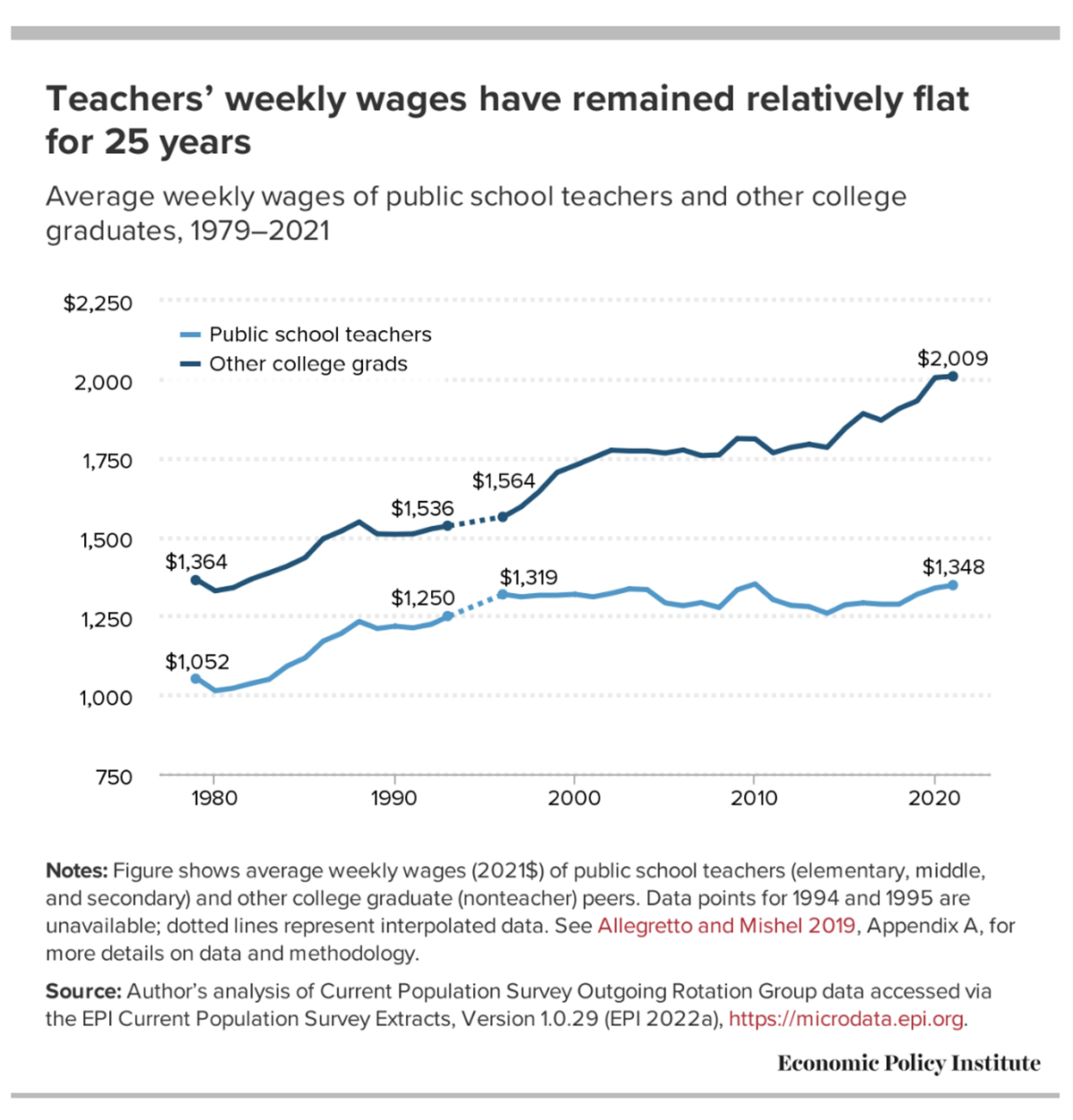

Top of mind for many contemplating the career amid a recession is compensation. Teachers’ weekly wages have remained relatively flat for 25 years; and educators earn about 24% less than peer grads, according to an August Economic Policy Institute report that looks at wages through 2021.

“People want a great return on investment in terms of a career and how their career will compensate them relative to the cost and especially any debt that they incur… Unfortunately, teaching is perceived as a low prestige, low paying profession,” Hearn said. “Prospective teachers are having to go into quite a bit of debt … that’s a huge pain point for people who are interested.”

Some teaching candidates are discontinuing their programs under financial stress, according to Mary Burbank, the University of Utah’s associate dean for teacher education. It was her first time witnessing the trend in her nearly three decades with the University.

“Instead of continuing their academic program, even with additional financial support, they could not afford to do that. [They’d] consider degree-only or alternative routes because the family needed support,” she said.

In the fall of 2020 and 2021, about 20% of traditional teacher education programs said the pandemic caused enrollment drops by 11% or more among undergraduates.

The pipeline in Oklahoma, which has some of the lowest average teaching salaries in the nation, is further limited by pandemic-era challenges.

“There are multiple distractions and disruptions thrusting Oklahoma educators in a whirlwind of pressures, dystopian narratives, and harassment from groups that know little if nothing about what it means to be a professional educator,” Shelbie Witte, head of Oklahoma State University’s school of teaching and learning, told The 74 by email. “Does this impact the state’s teacher pipeline and retention? 100%.”

Historic declines in community college enrollment, particularly among students of color, inflame a sense of urgency to strengthen pipelines. Nearly 40% of students who eventually study education at 4-year universities enter as transfers; at schools like Arizona State University, with transfers comprising more than half of enrolled students.

Making pathways to the profession more accessible, without sacrificing quality

Yet there are attempts to build up pipelines — states sponsoring educators’ tuition and fees or limiting reliance on alternative certification; undergraduates flooding introduction to teaching courses; and district partnerships to find possible candidates as early as high school.

At the request of rural districts and candidates seeking better access, Oklahoma State University recently launched an online program for elementary education. Arizona State University similarly made their pandemic-era hybrid options permanent, for rural and working students who need more flexibility to persist through graduation.

ASU has seen consistently strong enrollment, with the 2,841 students enrolled this fall being about 150 more than in Fall 2019. There, the threat of going into substantial debt is less pressing, thanks to the state’s Teacher Academy, a program that covers tuition and fees at participating universities.

The school has been on the forefront of innovations to teaching – piloting a team teaching model with the state’s largest district to reduce shortages and help new teachers feel belonging.

The school’s northern neighbor, the University of Utah, had similarly stable enrollment numbers this fall.

The state’s unique culture could be helping the situation — teaching is seen as a worthwhile, popular profession, Utah’s Burbank said. Their program works with five school districts to identify prospective teachers in high school, offering tuition support for a 2+2 program with a community college and the University.

They’ve seen growing interest in the field, even among non-education majors: This fall, 60 students are enrolled in the University’s Introduction to Teaching course — interest has grown stronger over the years.

“Honestly I was very surprised to see that,” she said, “I asked them why are you here and there is a spirit of wanting to make a difference.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)