To Test or Not to Test: Students Missed a Lot of Learning This Spring, but Experts Disagree on How — or Even Whether — to Measure ‘COVID Slide’

When Melissa Brennan begins school this fall at Mattie Lou Maxwell Elementary School in Anaheim, California, she’ll sit one-on-one with each of her special needs kindergartners and first-graders and take the time to assess their basic skills. Brennan expects that the process will take place not in person but over a videoconferencing platform.

“I’ll Zoom with them, and I’ll share an assessment on the screen, as if they were sitting in a class with me,” she said.

Though Brennan’s situation is unique — she typically teaches just a dozen or so students — she recommended that teachers with full class loads do the same.

As schools prepare to welcome back millions of students this fall, they must quickly figure out just how much progress students lost. Like engineers building a skyscraper, educators need to level-set a foundation before scaffolding on new, more advanced material. But figuring out how to measure the “COVID slide” is not as simple as it seems.

One thing is certain: U.S. students missed out on a lot of instructional time.

In Los Angeles, home to the nation’s second-largest school district, officials last spring said about 15,000 high school students had failed to do any schoolwork in the first few weeks after coronavirus shut their schools down, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Between March 23 and May 26, one-third of Providence Public Schools’ 24,000 students were considered chronically absent, The Boston Globe reported, meaning they lost at least 10 percent of school days. In Providence as elsewhere, the issue will take on added importance as many school districts plan to bring back students virtually, potentially replicating the conditions that allowed students to lose ground last spring.

‘Academic death spirals’

Teachers have already said their ability to cover new material last spring was badly compromised: In a RAND survey issued in May, just 12 percent said they covered “the full curriculum.”

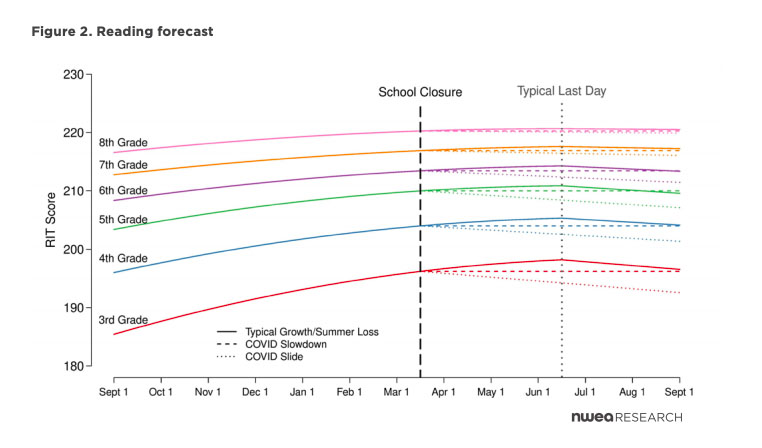

Researchers at the Northwest Evaluation Association predicted that students in a few grades could eventually lose nearly a full year of learning. And Kevin Huffman, the former education commissioner of Tennessee, warned that the pandemic could set back an entire generation of children.

Robin Lake, director of the University of Washington’s Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE), told Congress in May that without widespread efforts, many students “could go into academic death spirals.”

Speaking to reporters recently, Lake said, “What we do in the fall really matters. We know how to flatten the learning loss curve, but it will require information and assessments to be able to diagnose those learning losses quickly.”

The national shutdown could hardly have come at a worse time. In the thick of the pandemic, states scrapped their traditional year-end tests, with the support of U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. That removed a key indicator of how much students learned last spring.

But educators and advocates said that simply recycling those tests this fall won’t work.

“They’re not well-suited to turning around information to teachers and school leaders about how to tailor instruction,” said Charles Barone of Education Reform Now, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that has proposed widespread testing this fall. The organization says determining student academic achievement levels “will be essential to a successful transition” to the new school year. The group assembled a list of assessments it says can be used quickly and affordably.

‘We’re not doing mass retentions’

But some educators say that after students spent months at home in quarantine, suffering through glitchy Zoom meetings, stressed-out teachers and harried parents, the last thing they need is to sit for a battery of diagnostic tests.

Baltimore Schools CEO Sonja Santelises said summoning students for “an all-call cattle herd” of extensive testing is out of the question. “We’re not talking about a three-hour battery of testing, which I don’t think is healthy for either teachers or students right now,” she said.

Her teachers are working on ways to “compassionately and quickly assess” students as she strengthens the city’s tutoring corps. Santelises has ruled out holding entire groups of students back, even those who effectively checked out last spring. “We’re not doing mass retentions,” she said flatly.

Considering that most schooling in Baltimore will likely remain virtual in the fall, Santelises said, making decisions about student placements via online testing could also worsen inequality. For instance, an honors student whose family can’t get internet access shouldn’t be penalized in the fall for doing poorly on an online assessment or even skipping it altogether. “Does that student now cease to be an honors student because of these life conditions?”

Kevin Dykema, an eighth-grade math teacher in Mattawan, Michigan, said about one-fourth of his students weren’t particularly engaged in schoolwork last spring. But when the school year begins, he’ll start with traditional eighth-grade content. If he begins with seventh-grade content that his students missed, “I’m going to bore 80 percent of my class — and they don’t need to be bored” in math class. “Let’s get new stuff, and I can fill in those gaps along the way.”

Educators also say there are other ways to smooth the transition back to formal schooling. Groups such as the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics say schools should consider “looping,” assigning teachers to the same group of students they taught last spring, but with content appropriate to the fall term.

“It is important to start with grade-level content,” said Trena Wilkerson, NCTM’s president, who recommended “an asset-based approach, a strength-based approach. The students have been learning; they have been doing things. They’ve been engaged in mathematics as well as other disciplines. We need to build on that and not just assume they don’t know, but rather assume that if there’s something they don’t know, then we can address that during the academic year.”

Eric Kalenze, a Minneapolis high school English teacher who runs a research conference in the fall, said many adaptive tests may not be appropriate for this job, since they measure “raw academic skill, not necessarily what content was missed out on.” And asking students to take a test that doesn’t have tangible consequences means they won’t necessarily take it seriously.

He suggested that educators “think as locally as possible, and maybe put your energy into improving your formative assessment game.” Such tests can guide instruction but are rarely used in many schools. Educators should also figure out ways to quickly test students at strategic points during the year.

Making peace with boredom

That was one of the key findings of a panel of assessment experts convened by Lake at CRPE. “The truth is that kids have always been at different levels and had different needs,” she said.

The group, which released a white paper laying out seven principles for “effective assessment” during the pandemic, said students’ physical, social and emotional well-being should come first. It said students of color may be particularly anxious, “given the moment of racial reckoning happening in our country right now.”

The panel also noted that several high-quality curricula that schools already use may include assessments that can help guide instruction this fall.

“Start with what you have,” Lake urged school leaders.

Kalenze said districts should give teachers as many opportunities as possible to confer between grade levels “so they can say, both in terms of content and kids, ‘Here’s what’s coming to you.’”

But unlike Dykema, the Michigan math teacher, Kalenze said students should probably accept that material from last spring may come around again this fall. “Sorry, in this moment you’re going to be a little more bored than usual,” Kalenze said. He noted that cognitive science supports the idea that “practice makes permanent,” that periodic repetition helps material sink in.

In the end, he said, there’s a chance that all of that missed school may not be as cataclysmic as we suspect: Widespread closures began just as schools were winding down instruction and preparing for big, end-of-year summative tests that never happened. Though in many states closures began in March, he called May “probably your most worthless month of the year anyway. It’s the month that is co-opted by all of your standardized tests, all of your AP tests in high school, every year-end thing, every field trip.”

But CRPE’s Lake suggested that there may be more happening in most classrooms each May than we suspect. Even review work strengthens students’ abilities to retain what they learned earlier. “The reinforcement that happens in the spring is kind of a critical piece of the teaching and learning process,” she said.

Looking ahead, Santelises, the Baltimore Schools CEO, said the teachers and schools that were most successful during the closures were those that already had strong ties with students before the pandemic. “Our young people are going to need ways of building back relationships,” she said, “because the relationship piece is going to give us other data that the assessment data is not going to give us.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)