Title I Hinders State and Local Education Reform. It’s Time to Pare It Back

Domanico: Born during the Civil Rights Movement, the program was supposed to bolster learning to offer an escape from poverty. That goal was never met

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For almost 60 years, the federal government has imposed itself into the affairs of local schools and districts through its Title I program. The American people, both conservatives and progressives, have pushed back and demonstrated that they value local control of education. It is time to pare back or even end this program, as it is ill-suited to the emerging reformation in education policy occurring in state capitals and local school districts nationwide.

Nobly born at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Title I was originally construed as a funding stream to be targeted to a specific group of young people: those attending public or private schools with a high percentage of students from lower income families. Its laudable ideal, as expressed by then-President Lyndon Johnson, was that “poverty will no longer be a bar to learning, and learning shall offer an escape from poverty. … For this truly is the key which can unlock the door to a great society.” As I demonstrate in my new Manhattan Institute report, that goal was never met. Over the decades, Title I was repeatedly modified and now emphasizes general school improvement efforts while requiring states to measure student achievement and academic differences across racial and economic groups.

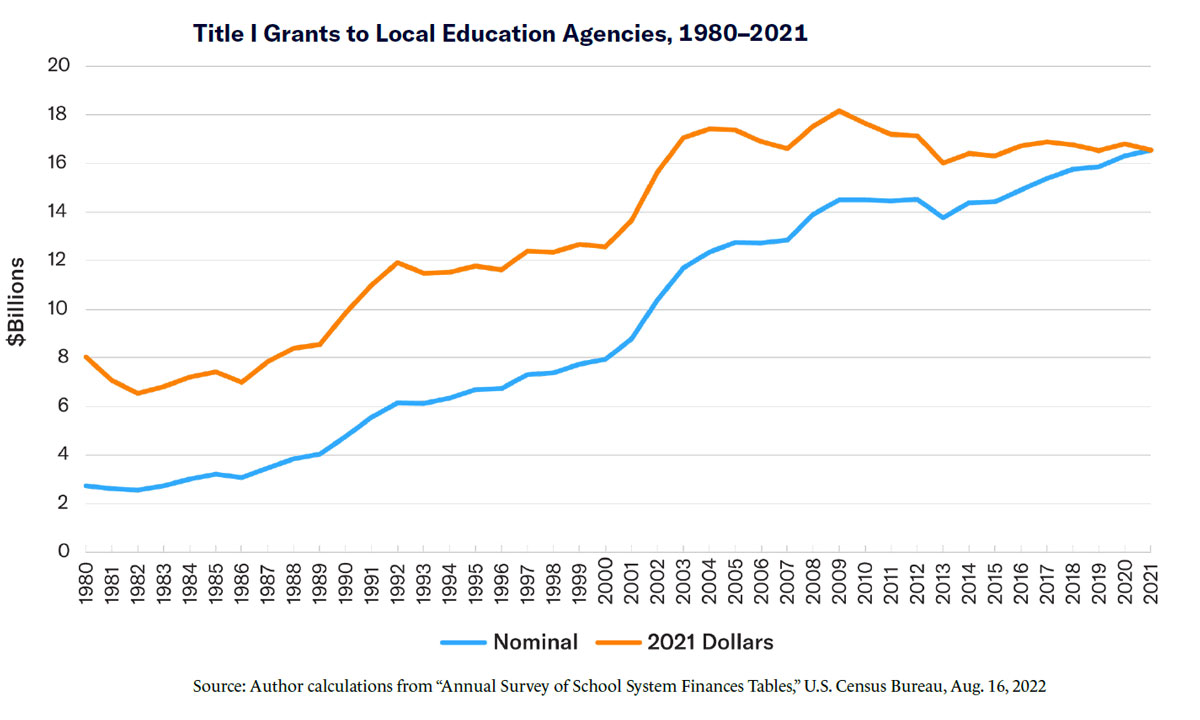

Since the dawn of the school reform era in the 1980s, the federal government has lagged behind innovative efforts at the state and local levels, often taking what it deemed to be the most promising of those initiatives and imposing them on all states and localities. Yet, federal spending accounts for little more than 10% of school district revenues, with Title I being the largest component.

Federal interference in education policy has had two high water marks. The first was the judicial effort to undo legalized racial segregation in the 1950s and 1960s. Title I was born in that era and added federal funds to the effort to undo the impact of discrimination. The second occurred in the second term of President Barack Obama, from 2013 to 2017, which capped the efforts of a Washington-based, bipartisan consensus on school reform that emerged over the Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama presidencies. Under the umbrella of Common Core and Race to the Top, this effort tried to incentivize states to adopt curricular standards aligned with the general guidelines of the Common Core, and to adopt one of two standardized tests whose scores could be compared.

Though popular in Washington, this effort fell apart when states began to implement it. The American people value local control of education and pushed back against both the Common Core and its attendant tests. The problem was that the Washington-based compromises appealed to only the policy wonks themselves. Suburban parents did not embrace testing standards that identified proficiency solely with college readiness and began withholding their children from the testing regime. Social conservatives distrusted the attempt to fashion school curriculum around Washington’s values. Progressives were wary of what they saw as corporate influence in the testing and assessment schemes. In short, groups that agree on little else agreed that Washington had overstepped its bounds.

This pushback, as well as discontent with schooling due to pandemic closures (motivated by federal guidelines responding to teachers union pressure) has given rise to a new era of local and state activism in education policy. In the last two years, eight states have adopted family school choice in the form of education savings accounts, which provide universal or nearly universal access to private and religious schools with public money.

At the same time, various states have moved to require schools to disclose the content of their curricula, and debates over the age-appropriate nature of lessons on sexuality and gender identity have moved to the local school district level, where elected school board members are ultimately answerable to the communities they serve.

In this context, Title I has become a wedge for federal involvement in conflicts around educational content and other school policies. It has become the hammer that the U.S. Department of Education uses to pursue its own policy agenda through “Dear Colleague” letters and broad investigations into school practices. Attempting to override local preferences, the department threatens the loss of Title I funding to noncompliant districts and schools. The problem is that people on both sides feel strongly about these issues, and solutions forged in Washington are likely to build resentment and damage the trust among parents, schools and communities that is so critical to school effectiveness.

If Congress ever returns to functionality, it should make clear that Title I funds may not be used to pressure school districts to comply with the department on policy matters that are rightfully left to local control. This does not mean that the federal Office of Civil Rights should not pursue remedies to specific violations of civil rights as codified in the Constitution or federal law, but it should not expand the scope of those rights as a matter of executive action. It should also require that Title I funds be directed to participating families, not to local school districts, in states that have universal school choice programs.

In the likely case that congressional action fails to materialize, governors and legislators in individual states should ask themselves whether the acceptance of federal funding, about 10% of school district revenue, is worth the interference that comes with it.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)