Thousands of Native Students Go to Albuquerque Schools. Most Will Never Have a Native Teacher

District officials started a state-funded pilot program this school year to hire more Native American teachers

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Growing up in Albuquerque, high school junior Brook Chavez, who is Diné, never had a Native American teacher until last year, when she took a Navajo language and culture class.

There, the 16 year old learned more about her culture and connected with other Diné youth, coming away prouder about who she is. She felt understood by her teacher, David Scott, also Diné, in ways she hasn’t always in the classroom.

“I learned a lot about my clans, my stories,” Chavez said, adding that at the end of the first semester, she and her classmates performed at Native American Winter Stories, an Albuquerque Public Schools (APS) event. “That’s one of my fondest memories because I got to dress up traditional with all my friends.”

Chavez just wishes she hadn’t had to wait so long.

There’s consensus among advocates and education officials that it’s important for teacher workforces to be representative of student populations, which research shows is linked to better student outcomes. Same-race teachers can act as important advocates and role models.

But Chavez’s experience is one that many Native American children attending school in Albuquerque are unlikely to have in the classroom, at least in the near future.

While parents of nearly 10% of APS students report they have tribal affiliations, only 1.2% of teachers the district employed during the last school year were Native American, according to district data.

The state Public Education Department identified increasing racial diversity among teachers as a priority in its draft plan released in May in response to Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico, a 2018 court ruling that found the state has failed to provide an adequate education to Native children, among other student groups.

And district officials in Albuquerque say they’re working to hire more Native American teachers. As part of that effort, they’ve started a state-funded pilot program this school year.

But challenges stand in the way, including increasing living costs in the city and a less-than-robust educator pipeline.

“Many of our children will never see a Native American teacher in their entire school career and that’s simply because the pipeline is not there to support Native Americans as they come out of high school,” said Rep. Derrick Lente, D-Sandia Pueblo, who for the past several years has sponsored legislation aimed at improving education for Native children.

Diversity gaps

There is a sizable Native American population in Albuquerque, New Mexico’s largest city and home to one of the largest school districts in the nation, with 73,346 students as of the last school year.

A significant number of those students are Native American.

When parents enroll their children in Albuquerque Public Schools, they report their children’s race and ethnicity to the district. During the last school year, 5.2% of students were recorded as being Native American, but 9.8% of students were reported by their parents as having tribal affiliations.

The latter figure is more representative of the actual number of students identifying as Native American, said Philip Farson, senior director of the district’s Indian Education Department. Many students are multiracial, Farson said, and end up being recorded as a race other than Native American despite their tribal affiliations.

A student census shows students from over 100 tribal nations and communities, the Navajo Nation accounting for the majority, with about 57% of Native students. There are significant populations from Laguna and Zuni Pueblos and a large number of students from tribes outside of the U.S., mostly in Mexico and Canada, according to the district.

In total, 7,192 students reported tribal affiliations. Meanwhile, the district employed 65 Native American teachers during the last school year. That means that for every Native teacher, there were about 110 Native children.

That gap has only slightly narrowed over the past decade. In the 2011-2012 school year, for every Native teacher, there were 117 Native children.

Having enough teachers that share the same race or ethnicity of students isn’t just a struggle involving Native students.

There are also significantly fewer Hispanic teachers than students – with 28% of teachers identifying as Hispanic compared to a student population that is two-thirds Hispanic.

“I think this is an unfortunate theme across the nation, really,” Lente said. “It’s not just in the Albuquerque public school system, it’s not just in New Mexico, but it’s across the nation.”

Indeed, gaps in racial diversity between teachers and students, as Lente pointed out, are both state and national trends.

During the last school year, 10% of students in New Mexico public schools were Native American while 3% of teachers were Native, according to the state education department. White students made up 23% of the overall population, while 59% of teachers were white.

Nationally, about 79% of public school teachers identified as non-Hispanic white during the 2017-2018 school year, while only 47% of students were white, according to a Pew Research Center analysis last year.

The importance of representation

Education officials, advocates and students alike agree that closing those diversity gaps is crucial in improving students’ overall experiences and boosting their academic achievements. There’s a substantial body of research that backs that up.

For instance, Black students are 13% more likely to graduate high school and 19% more likely to enroll in college if they had at least one Black teacher by third grade, according to a 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research study.

Researchers say there are likely a combination of factors that explain why teachers’ race, as well as their gender, matters, the New York Times reported, including that same-race teachers may introduce new material in a way that’s more culturally relevant.

Teachers who understand where their students come from can act as advocates, said Dr. Glenabah Martinez (Taos Pueblo/Diné), a professor in the University of New Mexico’s (UNM) Department of Language, Literacy and Sociocultural Studies.

As an example, Martinez cited Native American students possibly needing to be absent for a number of days to participate in ceremonies in their tribal communities.

“If a teacher is from that same community, that teacher completely understands why that student needs to participate and how that student isn’t just missing the white man’s school, the Western school, but they are getting a different type of education that is intensive in terms of the cultural knowledge,” Martinez said. “A Native teacher understands that and they can therefore advocate for that student.”

She also said it’s important for school districts to have Native American administrators who can guide the creation of culturally relevant curriculum and policies.

For Chavez, who’s in her junior year at La Cueva High School, having a Native teacher meant that she felt a level of support and acceptance she rarely felt in earlier grades.

She remembers other kids calling her “Indian” and “Pocahontas” in elementary school, and the climate at her high school — where 4.7% of students have tribal affiliations, according to district data for the last school year — isn’t much better, she said. Teachers sometimes single her out, turning to her during lessons that feature Native American cultures or historical figures — regardless of whether they have anything to do with the Navajo Nation — and asking her to weigh in.

“They’ll say, ‘Oh, you’re Native, you should tell us more about it,’” said Chavez, who’s a member of the Native American Student Union at her school.

Scott’s class was a reprieve. Two days a week, Chavez and a handful of other students from around the city rode buses to the classroom. She became close with some of her peers, who she stays in touch with despite no longer sharing a class.

“My students said they felt better coming in,” Scott said. “They felt like they belonged, as opposed to when they were at their school they were kind of ridiculed and ashamed to say who they were…I told them, you just have to stand your ground but be proud of who you are.”

Scott shared with his students that as a boy, he stayed with his aunt in Texas for the summer and other kids asked him how long it took him to set up his tipi. In college, his peers assumed he was getting a monthly check from the casino, he said.

“I just told them [his students], prepare yourself, educate them,” he said.

Chavez wouldn’t have had Scott as a teacher had she not made the effort to take a Navajo language course, which involved traveling to another campus twice a week.

Scott is one of six Navajo language teachers that APS employs.

To meet the language programming needs of the roughly 4,000 students affiliated with the Navajo Nation, Farson said the district would need to hire up to 100 Navajo language teachers over the next few years.

As of late August, about 200 Diné students are enrolled in language classes, according to district spokeswoman Monica Armenta, and 40 Zuni students are enrolled in language classes taught by the two Zuni language teachers the district employs.

Chavez desperately wants to keep learning the Navajo language, but there’s not a higher level class she can take this year. She worries she’ll never be fluent.

Part of why she opted to take Scott’s class was because it meant “keeping the culture alive.” Her grandma, who was sent to a boarding school as a child, is the last fluent Navajo speaker in her family, and her sister and cousins aren’t interested in learning, Chavez said.

The federal government, beginning in the early 1800s, removed Native children from their families and sent them to schools designed to strip them of their cultures. Abuse ran rampant and hundreds of children died, according to an investigative report the U.S. Department of the Interior released in May, although the department expects that number could rise to the tens of thousands with continued investigation.

“My grandma didn’t want to teach her kids Navajo because of what happened to her,” Chavez said. “She talks about it now but she still says she’s a little scared. She’s really traumatized by the boarding school.”

Not enough

Albuquerque district officials said they recognize hiring more Native teachers is important but they’re drawing from a limited supply.

“The district could declare that 5% of our positions have to be filled by Native American educators but they’d run into the reality that there aren’t enough Native American educators to go around,” Farson, APS’s Indian Education Department director, said.

The department also struggles with retention because the pay, at least for leadership positions, isn’t competitive, Farson said.

“When we find qualified talent, how do we keep it? That’s our challenge.”

Some Native teachers the district does employ echo Farson, pointing to a lack of affordable housing in the city.

“I was looking but rent is so high and teachers’ pay is not enough to cover it, to even survive on,” said Scott, who began teaching the Navajo language in Albuquerque last year. He commuted the entire school year from Naschitti, which is north of Gallup. It’s more than a five-hour round trip. “A couple times, probably three times, I just slept in my vehicle.”

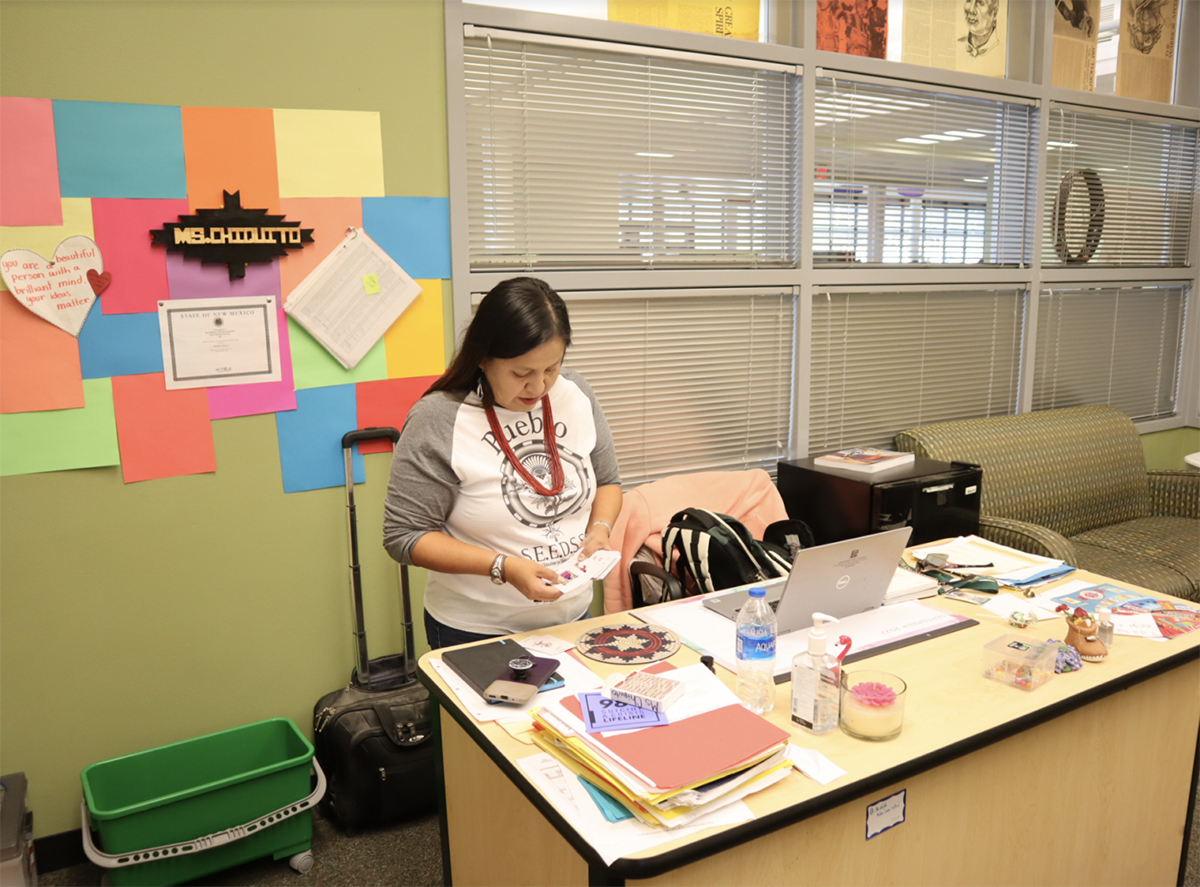

Mildred Chiquito, who teaches Navajo at Atrisco Heritage Academy High School, lives in Torreon, about 85 miles northwest of the school, with her elderly parents and her 17-year-old daughter.

She wishes there was teacher housing in Albuquerque.

“It’s hard paying for electricity, water and stuff in the city,” Chiquito said. “Some teachers are single parents and they’re just trying to make ends meet…I told my parents if I had teacher housing in Albuquerque, I would take them there and they would stay with me three days out of the week or something and then we go home, back on the reservation.”

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ State of the Nation’s Housing report for 2022 indicates double-digit increases in Albuquerque area rents.

Some school districts across the country, including in California and Colorado, have recently asked parents to temporarily house teachers. One district south of San Francisco recently built a 122-unit apartment complex for teachers and staff on district property.

Chiquito said that while she would like to live in the city on weekdays, the drive is worth it.

“I love what I do and I love just giving back to the school and I don’t mind the sacrifices of driving,” she said.

She began over a decade ago when she received a certification that allows people who are experts in the language and culture of a specific tribe or pueblo but don’t necessarily have a college degree to teach in K-12 schools. In March, the Legislature passed a bill establishing equal pay for Native language teachers such as Chiquito.

When it comes to recruiting Native teachers, there’s also somewhat of an urban and rural divide.

Martinez, the UNM professor, is heading up a program that aims to help Native people become teachers and work in their home communities.

“We can’t forget that we need teachers who are committed to their own Native communities, to a Native community because they care about the community and it’s located in an area that’s maybe not close to the malls and the 24-hour coffee shops,” Martinez said. “I think we need teachers all over the place, rural and urban, but we’re doing a more concerted effort to recruit Native teachers to be teachers in their own communities so they don’t have to move to Albuquerque.”

Pipeline focused on Native students doesn’t exist, yet

Earlier this year, APS received a $200,000 grant from the state education department’s Indigenous Education Initiative to place a teacher with experience working with Native students along with a coordinator for three years at Mission Avenue STEM Magnet School, where about 20% of students are Native.

“It’s trying to take an in-depth look at, not only how are students connected and represented within the curriculum of the school, but the staffing of the school,” Farson said, adding that by the end of the program, the school is expected to have a staff that’s representative of the student body. “My hope is that in that process we’ll really be able to surface the real issues and challenges and a plan for how to address them across the district and not just at one school.”

The district recently hired a teacher who’s set to start later this month. The coordinator position is still vacant.

In his experience with similar grant-funded programs, Farson said the first year “is always a bit rough” but the district eventually fills the positions.

Rather than trying to recruit teachers from around the state, Farson said the long-term solution is to build locally.

“Over time, our real solution is to figure out how to develop the interests of those 7,000 students who have tribal affiliations here in APS to want to become educators and stay here,” Farson said.

State and district education officials cite a number of programs centered around pipeline development, but none of them target Native people in particular, and most don’t target high schoolers.

There’s the district’s teacher residency program, which pairs people pursuing a degree in education with an experienced co-teacher at a high-need school for 15 months. Residents agree to teach within the district for an additional three years after completing the state-funded program, which the district runs in partnership with UNM and the Albuquerque Teachers Federation.

There’s also a residency program with Central New Mexico Community College specifically for special education.

The majority of residents across both programs — about 120 people — are still teaching in the district, according to Valerie Hoose, executive director of labor relations and staffing for the district.

The district also participates in the state education department’s two-year Educator Fellows program, geared toward educational assistants who want to become certified educators. Fellows receive hands-on experience, mentorship, and a stipend.

“We’re hoping to stop that bottleneck that happens in the teacher pipeline where we have a lot of people that graduate out of programs and don’t sustain in the field,” said Layla Dehaiman, director of the department’s educator quality and ethics division.

While people have to be over 18 to take part in the program, Dehaiman said department staff have been reaching out to high school seniors and have recruited several recent graduates.

Dehaiman said the department has also been holding a Native American teacher working group over the past year that’s focused on barriers to licensure and long-term recruitment strategies.

Hoose said that getting young people interested in becoming educators is challenging partly because there’s a lot of competition for workers, adding that a widely available internship program for high schoolers might be a useful tool.

“We have a lot of CTE [career technical education] around the state and I think if education was one of those, where students could have access to information and experiences around teaching, that would be helpful,” Hoose said.

One future teacher might be Chavez.

With high school graduation in sight, Chavez has been giving some thought to potential careers. While she’s concerned she wouldn’t make enough money in education, she said teaching’s always been an aspiration of hers.

“I want to be a supportive teacher that I didn’t have growing up,” Chavez said. “A lot of these Native kids are going unnoticed.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)