This Week’s ESSA News: And Then There Were 6: A Look at How — and Why — 6 States Have Yet to Get Their ESSA Plans Approved

This update on the Every Student Succeeds Act and the education plans now being refined by state legislatures is produced in partnership with ESSA Essentials, a new series from the Collaborative for Student Success. It’s an offshoot of their ESSA Advance newsletter, which you can sign up for here! (See our recent ESSA updates from previous weeks right here.)

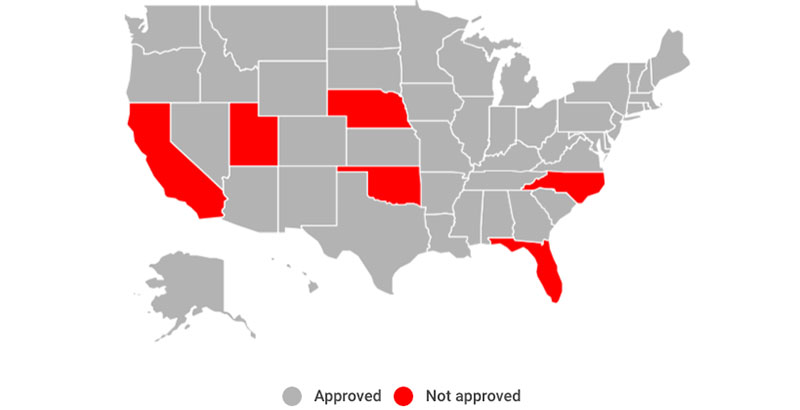

The U.S. Department of Education has approved 44 state ESSA plans (plus those from the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) so far. Which states remain in federal approval limbo? What are the problem with these plans? What have these states done — if anything — to update their ESSA plans to help earn the federal nod? Below, we take a look at these and other questions regarding the six remaining states: California, Florida, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Utah.

1 California

According to the Los Angeles Times, in December, the U.S. Department of Education requested that California resubmit its ESSA plan, which state education officials said was light on details “because anything promised amounts to a contract with the Trump administration.” The Education Department’s letter stated that California had “not sufficiently ‘provided long-term goals for all students’ and each group of students” and that the plan lacked “goals for improving high school performance” and “leaves too much in the hands of districts when it comes to measuring certain aspects of progress.” Federal officials also noted there are “holes in how the state would identify and help underperforming schools.”

In April, California submitted an updated ESSA plan that, according to Education Week, “meets the federal demand to flag schools in the bottom 5 percent of performers in the state.” And, in order to be compliant, the state chose to identify low-performing schools as those that do “very poorly or poorly on half or more of the indicators” measured by the state’s dashboard. The state also “tweaked its plan to measure a school or district’s improvement or decline over time in a way that was more consistent with ESSA” and “made changes to the way 11th grade tests figure into school ratings.” The new plan also redefines English-language proficiency to conform better to ESSA’s relevant provisions.

The Check State Plans analysis of California’s ESSA plan submitted in September identified several weaknesses, including an overall need for additional detail, a dashboard accountability system that is “complicated and incomplete,” a lack of definition as to its method for using this dashboard to identify struggling schools or subgroups, and an inability to measure individual student growth over time. The analysis says California “should move to adopt an individual student growth measure into its accountability framework to encourage schools to improve both student proficiency and growth.”

2 Florida

The Tampa Bay Times’s Jeffrey Solochek reported in December that the U.S. Department of Education told Florida education officials that the state “can’t simply adopt rules that run counter to” ESSA, including changing the way the state approaches tests in languages other than English — “particularly without seeking waivers.” The Education Department’s letter also “took issue with the state’s plan to exempt certain eighth graders from inclusion in assessing middle school math performance” and “challenged the state’s method of accounting for demographic subgroups in measuring achievement.”

In response to the issues raised by federal officials, Florida submitted its revised ESSA plan on April 20 to address these concerns. In the revised plan, Florida developed a federal index that will account for English language proficiency and will exist alongside the state’s A–F school grading system. The index and A–F grading system will both be used to identify schools that are in need of assistance. Additionally, Florida has, according to Alyson Klein, “added language to its plan saying it will consider individual subgroup performance, not just overall school grades, in identifying schools for ‘targeted support’ under the law.”

The Check State Plans reviewers also found that Florida’s plan submitted in September was lacking in several key areas that mirror the concerns of federal officials, including the state’s “approach to incorporating subgroups in its accountability system,” a lack of individual subgroup data in its A–F grading system, a lack of clarity regarding whether “schools could receive high grades even if individual subgroups are performing poorly,” a too-strong emphasis on overall school performance averages, and a lack of “an indicator of progress toward English language proficiency.” The plan also does nothing to provide “any accommodations or supports for its significant portion of students who are English learners.”

3 Nebraska

The Associated Press reported that the U.S. Department of Education questioned several aspects of Nebraska’s ESSA plan, specifically regarding how the state plans to “meet annual reporting requirements under the new education law.” Education Week provided more detail, noting that the federal agency disapproved of the state’s plan to use “a minimum number of assessments, rather than students,” as its minimum n-size.

The state also must define English proficiency under its ESSA plan and ensure that it counts as a “separate indicator” in its system, as well as clarify how much weight each indicator in its accountability system is assigned, so federal officials can ensure that academics are “given more consideration than other factors.” Finally, the state’s plan also “got hit” for its use of scale scores. Nebraska submitted a revised ESSA plan in April.

Based on a September version, the Check State Plans analysis says that while Nebraska’s “vision is ambitious,” its “plan lacks detail,” as evidenced by its failure to “connect the dots” between its goals, accountability system, and method of identifying struggling schools. The state has also “not given any indication of how it would hold schools accountable for low-performing subgroups of students.” Nebraska’s four-tier system “doesn’t differentiate how a school is actually performing,” and the plan provides no details regarding accountability for schools with low-performing subgroups. More broadly, there are a “variety of instances where Nebraska takes an unnecessarily complicated approach.”

4 North Carolina

In December, the U.S. Department of Education sent a letter to North Carolina education officials seeking more information on topics such as how school quality and academic factors will be calculated under the state’s ESSA plan, as well as the system by which they will be weighted. The feds also said North Carolina’s plan must improve its system for demonstrating consistent improvement in schools to allow state education officials to properly determine when a school can return to “normal” from “low-performing” status.

Additionally, the state’s plan needs to reconfigure its system for ensuring that low-income students receive adequate resources, including access to qualified teachers, and the state needs to move more quickly to provide extra help for struggling schools. In February, North Carolina submitted a revised plan to federal officials.

The peer reviewers who conducted the Check State Plans analysis of the September version of North Carolina’s plan found plenty they didn’t like, including an overall lack of coherence between “state goals, accountability indicators, and the public accountability structure,” as well as a systemic overweighting of current achievement “relative to progress over time.” Additionally, despite inclusion of an A–F school grading system, the “plan does not always articulate a clear relationship between those letter grades and the state accountability system,” and there is a lack of urgency when it comes to identifying schools with low-performing subgroups and weak exit criteria for support.

5 Oklahoma

The Oklahoman reported in December that the U.S. Department of Education had requested “additional details and clarifications” before it could give Oklahoma’s ESSA plan final approval. In total, the Department asked for clarification or more information on dozens of aspects of Oklahoma’s plan, including wanting to know how state education officials plan to “track student growth among various student subgroups” and “how struggling schools exit an improvement plan,” as well as the process by which English language proficiency will be calculated for individual schools. A spokesperson for the state Department of Education said this feedback was “not unexpected,” because a number of the federal agency’s questions “stemmed from data that had not been available at the time of the plan’s submission deadline.”

Check State Plans found that Oklahoma’s plan as it was submitted in September includes an “overall uncertainty and lack of detail” that make it hard to determine the state’s long-term goals. The plan does not provide academic achievement targets, and it “has not yet settled on a definition for how it will measure achievement in its accountability system” or how low-performing schools can exit improvement status. At the same time, the “bar appears to be set very low for schools to show improvement,” and it is unclear whether struggling schools will receive adequate support. Additionally, the plan assigns students to only one subgroup, regardless of whether they qualify for multiple groups, and the penalty for schools failing to hit participation rate requirements “does not provide a sufficient incentive” to ensure all students, “especially historically low-performing subgroups of students,” take part in assessments.

6 Utah

According to Education Week’s Alyson Klein, the Department of Education told Utah in December that the state “needs to spell out its long-term goals for math and reading, and for English-language learners to attain proficiency” in its original ESSA plan. Federal officials also said the state needs to “make it clear whether it is using the ACT or some other assessment as its test for high school students.”

Additionally, the Utah plan proposed allowing local school districts to determine their own factors to measure school quality and student success. However, if these factors “are used in state accountability determinations, the department is worried not every school will be held accountable for the same indicators.” It remains unclear whether factors such as English language proficiency, graduation rates, and exam results will “make up at least half of a school’s overall rating in Utah’s system, as required by ESSA,” the Education Department said in its letter to state officials. Utah submitted a revised ESSA plan in March

According to the Check State Plans analysis of Utah’s plan as it was submitted in September, the “state does not directly incorporate individual subgroup performance into a school’s rating,” and it omits key details for aspects of its plan, such as “the grading scale that distinguishes the final grade a school receives,” and likely has “set too low a bar for students.” Additionally, the plan provides little information about “the actions and strategies that will be implemented to improve low-performing schools,” and it fails to “provide sufficient detail about its ongoing activities to engage stakeholders and educators.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)