Thinking Like a Computer: Excel Charter School Teaches Kids to Break Down Complex Problems

The Seventy Four reports on the Washington Supreme Court decision: Read our complete coverage

(Kent, Washington) – It’s Friday morning at Excel Public Charter School, and students are building paper towers to test on an earthquake simulator. Others are holding a classwide debate on allowing Syrian refugees into the U.S. Still others are designing websites about ancient Egyptian history.

Some of these students are using computers. Some are not. But all are attempting to think like one.

It’s called computational thinking, a learning model developed for Excel in part by the school’s computer science teacher, Taylor Williams.

“Computational thinking is the idea that computer science is more than just programming and that every single student can benefit from learning computer science ideas,” Williams said.

Izabella Bides and Ryan Louie practice during orchestra class at Excel Public Charter School in Kent, Washington.

Photo: Kate Stringer

Students dissect complex problems into steps and use computer science vocabulary — algorithm, abstraction, decomposition — to understand their assignments. They do it in computer science class and they do it in English class and they do it in orchestra class.

Algo-what? That was the initial reaction from students when Excel introduced them to computational thinking. But as Eli Sheldon, Excel’s computational thinking program manager said, the approach to computational thinking has grown positive and every student can now define it.

For example:

“Computational thinking is using your common sense and using it on a problem,” sixth-grader Harpneet Kaur said.

“Computational thinking is thinking about something that you don’t know or understand and thinking hard about it,” sixth-grader Eden Fenta said.

Both Fenta and Kaur found computational thinking challenging at first, but said their teachers are good at incorporating it into the lessons. The sixth-grade girls are friends, love science class, and dream of becoming pediatricians.

That’s a good sign for Washington state, where only 9 percent of students end up working in STEM jobs in their home state, according to a 2013 Boston Consulting Group and Washington Roundtable study. Even importing STEM talent cross-country and abroad leaves 25,000 jobs unfilled, a number expected to double next year. With tech giants like Microsoft, Amazon and Boeing sitting in Kent’s backyard, school Founder and Executive Director Adel Sefrioui sees an opportunity lost.

“My philosophy is why not cultivate the talent now with our kids?” Sefrioui said.

Excel is one of a handful of Seattle-area schools that offers computer science class, and the only one that requires it for graduation. (The 74: Nearly 20,000 Sign Petition Calling on California Colleges to Recognize High School Computer Science Credits)

Hawo Issa files into class with her Excel Public Charter School peers.

Photo: Kate Stringer

But the charter school has been threatened by the ongoing legislative battle after the state Supreme Court ruled Washington’s eight charters unconstitutional in September. Charter supporters cheered as the Senate and then last week the House passed a bill to keep the schools alive. Now the critical legislation awaits Gov. Jay Inslee’s signature.

“We’re thankful and relieved and cautiously optimistic that the governor will sign this bill,” Sefrioui said. “Our families became louder and called and went to Olympia. We’re really proud of our school’s legislators.”

If the governor lets charter schools live, Excel can carry on with its mission to not only teach computer science, but the values that come from thinking like a computer.

Humanities teacher Cristina Marcalow works with sixth-grader Eden Fenta Friday morning at Excel Public Charter School in Kent, Washington.

Photo: Kate Stringer

That job falls to Sheldon, the computational thinking program manager. He collaborates with classroom teachers to incorporate computational thinking skills into lessons. In math class, that can look like creating a speed chart using NBA data to analyze a LeBron James dunk. In social studies, students designed their own civilizations to calculate the impact of events like war, disease, natural disaster and geography.

Sheldon witnessed the real-world importance of computational thinking during his four years at Microsoft, where he worked as a program manager.

“You learn to tackle a problem that’s too hard for you by repeating and trying again,” Sheldon said. “You can decompose a problem that seems too complicated.”

Tight school budgets make jobs like Sheldon’s — getting to spend several days designing lesson plans that use computational thinking — rare. A grant from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation covers the salaries for Sheldon and Williams, the computer science teacher.

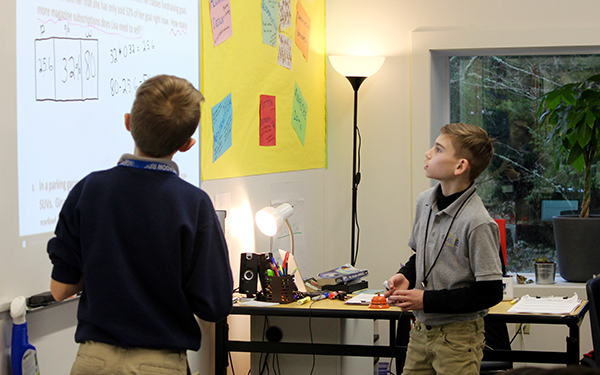

David Produsevich works on a math problem at Excel Public Charter School in Kent, Washington.

Photo: Kate Stringer

Sefrioui’s plans to grow the school and expand its unique learning model were halted after the Supreme Court ruling. The charter currently enrolls 130 sixth- and seventh graders, with plans to eventually go through 12th grade. Sefrioui said he wants to build another campus, but has put those ambitions on hold until Inslee takes action on the charter bill.

Computational thinking itself wasn’t the reason behind the creation of Excel, Sefrioui said. He saw a need for the charter in light of the failing public schools of South King County.

Sefrioui said he recruited heavily in low-income and minority housing complexes. The child of immigrant parents, Sefrioui saw the importance of diversity, both ethnically and socioeconomically, in his school. In the Kent School District alone, 130 languages are spoken.

Kent School District sixth-graders scored 60 percent proficient in reading and 55 percent proficient in math on the 2014-15 Smarter Balanced test (still above the state sixth-grade average of 54 and 45 percent, respectively).

But Sefrioui wanted to reach the other half who aren’t proficient. To increase learning time, Excel operates on a longer school day and year. Excel is in session 194 days vs. the mandated 180 days, which Sefrioui said eliminates lost learning during the summer. The school day runs from 8 a.m. to 3:45 p.m. Some 90 percent of Excel students participate in an optional after-school program that lasts until 4:45 p.m.

To maintain engagement during the lengthy school day, students participate in daily P.E. and orchestra class. Homerooms which emphasize organization begin and end each day. But ultimately it’s up to the teachers to create engaging and interactive lessons for students.

Professional development is also an important piece of Sefrioui’s plan for Excel, with four weeks in the summer and 10 days during the school year dedicated to Excel teachers.

For seventh-grade science teacher Elaine Chao, Excel is a place where she can finally work with a close-knit team focused on a unified goal:

“Every student can and should learn,” she said. “The difference is how we do it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)