These California School Districts Joined Forces to Bolster Social-Emotional Development, but a Study of 400,000 Kids Reveals Learning Gaps and a Confidence Crisis Among Middle School Girls

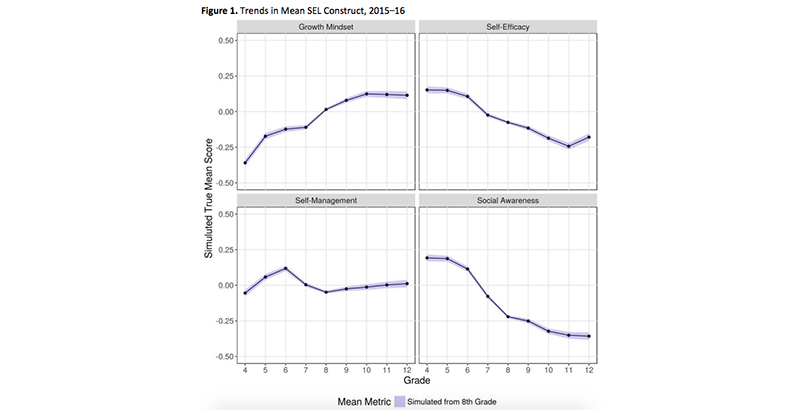

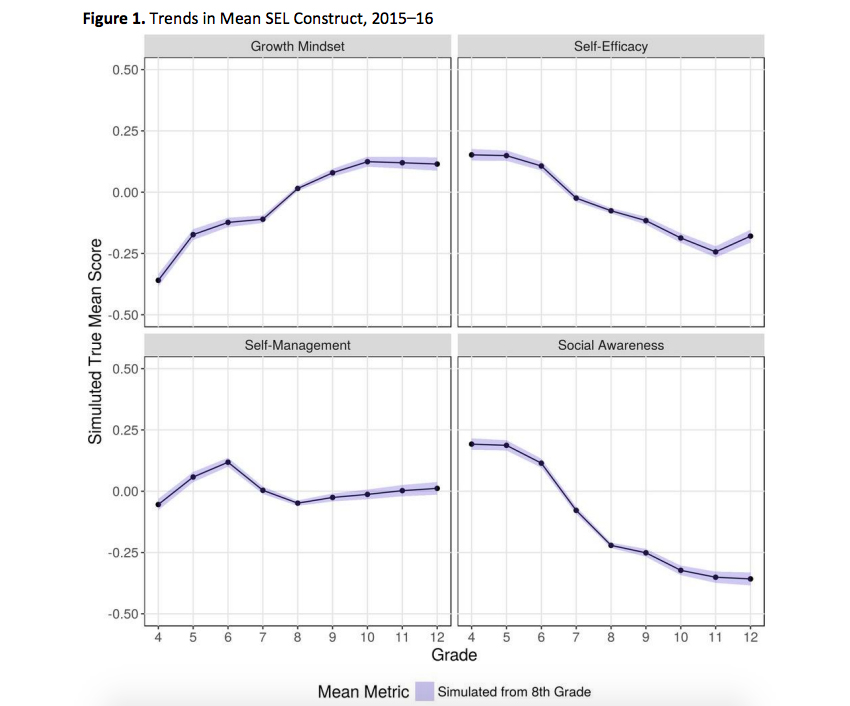

As they progress through school, students are getting better at believing they can master challenging subjects, but they are getting worse at managing their behavior and empathizing with others.

Those are highlights of a recent study of nearly 400,000 California students in some of the state’s largest school districts, which have collaborated over the past several years to teach and measure a common set of social-emotional learning skills.

But the study, which looked at how social-emotional learning developed from fourth to 12th grade, found that not all students are learning these skills at the same pace. Girls’ self-confidence plummets as they enter middle school, and white students consistently report higher social-emotional learning than their non-white peers.

Researchers used data from California’s CORE Districts, a network of large districts in Fresno, Garden Grove, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Francisco, and Santa Ana, that formed in 2010 to collaborate on education challenges, including social-emotional learning. The districts identified four skills they wanted to teach students — growth mindset, self-management, self-efficacy, and social awareness — and created a common survey to measure them annually. CORE also partnered with the research group PACE — Policy Analysis for California Education — to measure its progress.

While growth mindset increased between 2014 and 2016, researchers found that social awareness, self-efficacy, and to a smaller extent self-management decreased as students progressed through school. But these findings aren’t necessarily indicative of a failure on the schools’ part, said Martin West, associate professor of education at Harvard University, who worked on the study. Instead, they may speak to how little the field knows about how social-emotional skills develop over time and how to best measure them.

“I don’t think this data can speak directly to the success of individual CORE Districts to support students’ social-emotional development, in part because we just as a field don’t have much of a baseline,” West said. “This research is really an effort to try to begin building that baseline understanding of how students’ social-emotional skills develop as they move through school systems.”

The data also revealed how certain subgroups of students vary in their social-emotional development.

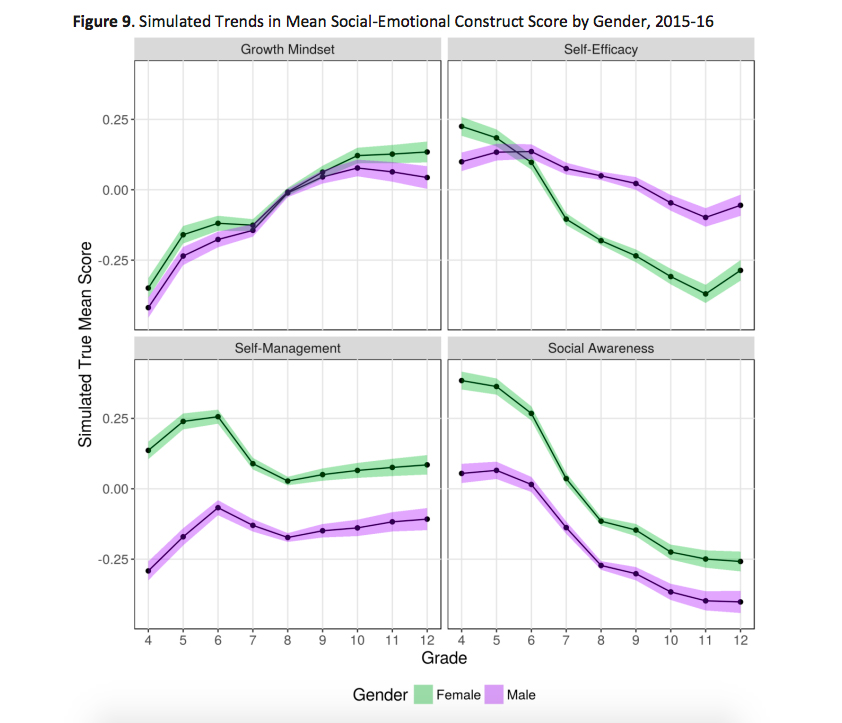

One of the most surprising findings for West was how girls’ self-efficacy — or belief in their ability to achieve — plummeted in middle school. Girls had higher confidence in themselves during elementary school than boys, but this changed in sixth grade and only started to increase between junior and senior year of high school. Boys’ self-efficacy also decreased during this period, but it was a modest decline compared with the trend for girls. Despite having low confidence, girls continued to perform significantly better in academics than their male peers.

Although academic self-efficacy can typically predict a student’s performance, West said this finding shows that the survey is not asking students solely about their confidence to succeed academically.

“There are a lot of things in here that we don’t know how to interpret,” West said. “With this project, we are trying to lay a foundation and raise questions as well as offer definitive answers, and I think [the self-efficacy finding] is a nice example of it.”

Girls also reported higher levels of self-management and social awareness than boys, though social awareness for both genders declined in middle school. Growth mindset trends were similar for both genders.

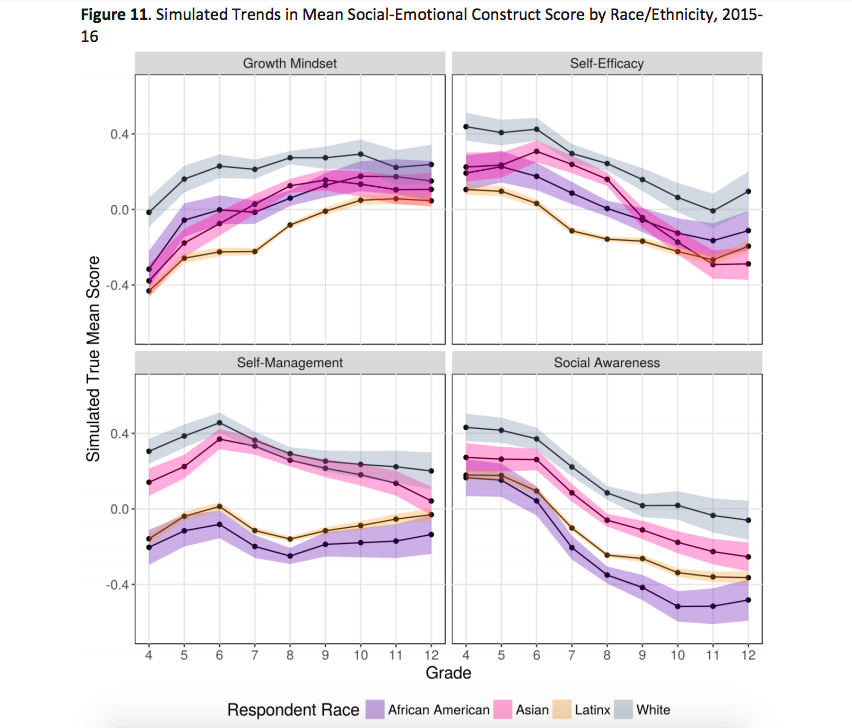

White students reported higher levels of social-emotional learning than Asian, Latino, and African-American students. Low-income students reported low levels of social-emotional skills, though some of these gaps narrowed in high school. The researchers noted that this could be reflective of the trauma that some students from disadvantaged backgrounds face as well as the fact that school culture and climate surveys show students of color often rate their schools as less friendly than their wealthier, white peers do.

It’s important for schools to see if there’s anything systemic that could be causing certain subgroups to lag behind their peers in these social-emotional skills, said Robert Jagers, an expert in social-emotional learning research who was not involved in the study. For example, he said some students might internalize biases from their teachers that could cause them to feel like they don’t belong or aren’t understood. Or those students could be in need of more support in certain social-emotional areas.

“Clearly the data are important and clearly they are telling us something, but we need to dig into the data more to understand these diverse groups of young people,” said Jagers, vice president for research at the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, a nonprofit that studies social-emotional learning.

One of the reasons students might have progressed in growth mindset more so than other areas is because educators might know how to teach that skill better than self-efficacy, self-management, and social awareness, West said. “I don’t think there’s a consensus on how best to cultivate students’ ability to manage their behavior,” West said.

There’s significant evidence that social-emotional learning can boost student graduation rates, improve academic performance, and lead to better life outcomes. But one of the challenges researchers are facing is how to measure how students are learning social-emotional skills.

Right now, the most common and scalable measurement tools are surveys. Although survey data have been shown to be a reliable predictor of behavioral outcomes, West said he urges caution when relying solely on such data because of biases that can appear when people are asked to evaluate themselves.

California has also administered student surveys called the Healthy Kids Survey, which schools could take every two years, and which was mandated if schools wanted to receive funding for drug prevention. But that initiative ended in 2010, EdSource reported, and now the survey is mandated for use in seventh, ninth, and 11th grades in exchange for funding around tobacco prevention.

CORE has a common set of social-emotional standards, but it doesn’t dictate how schools or districts teach it. Instead, the group serves as a resource for schools to learn from and collaborate with one another, said Noah Bookman, chief strategy officer of the CORE Districts. For example, CORE schools can tap into this baseline of student survey data to use as a comparison for their own school’s progress.

“It’s important to appreciate that collecting new data and understanding it is a journey and it takes time,” Bookman said. “It takes a mindset of, ‘What are we trying to learn, and are we going to be open to that learning?’ ”

Fresno Unified School District is one of the CORE Districts that has been surveying students for the past few years to measure social-emotional learning and school climate. But it’s not leaders’ only measurement tool — they also look at suspension rates, discipline, and office referrals.

To improve its students’ social-emotional skills, Fresno is embedding training directly into its middle and high school curriculum. For example, in English class, a teacher might talk to her students about empathy and how to understand the different perspectives of characters in a text.

Another focus for the district is building the emotional intelligence of its teachers. Right now, Fresno is turning to its teachers to help improve the feeling of connectedness students have to adults in the building, an area their surveys indicated could be better, said Ambra Dorsey, executive director of Fresno’s department of prevention and intervention.

Rita Baharian, director of climate and culture at Fresno, emphasized that a district of Fresno’s size can’t implement radical change each year based on survey results but instead will monitor student growth over time.

“We need to have a culture to value emotional intelligence just like we value our IQ,” Baharian said. “Students need to be explicitly taught these skills.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to the CORE Districts and The 74. The Walton Family Foundation provided financial support to the PACE research and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)