Resisting School Integration: A Brooklyn Case Study in Scared Parents and Bad Data

The Fact-Check is The Seventy Four’s ongoing series that examines the ways in which journalists, politicians and leaders misuse or misinterpret education data and research. See our complete Fact-Check archive.

They say it’s due to fear of sending their kids to a worse-performing school, but school-performance data tell a different story, suggesting that the real hurdles to integration include a misinterpretation of testing data as well as deep-seated prejudice.

The controversy centers around two public schools: P.S. 8 and P.S. 307. A Sept. 23 New York Times story shares some parents’ concerns: “At a meeting at P.S. 8 on Monday, Dumbo residents pointed to P.S. 307’s low test scores and asked what kind of training and extra resources the school’s teachers would receive to make the education there comparable to that at P.S. 8.”

Parents in P.S. 307, meanwhile, are also skeptical of the plan. “We fought hard to build this school, and we’re not just going to let people come from outside when we worked so hard and dedicated ourselves,” one parent explains.

The Times then points to the differences in school proficiency rates: “P.S. 307’s population is 90 percent black and Hispanic, and 90 percent of the students’ families receive some form of public assistance. Its state test scores, while below the citywide averages, are closer to average for black and Hispanic students, with 20 percent of its students passing the math tests and 12 percent passing the reading tests this past year. At P.S. 8, whose population is 59 percent white, with only 15 percent receiving assistance, scores are considerably above the city averages. Almost two-thirds of its students passed each test.” A Wall Street Journal story highlights the same stats.

Without quite saying so, we’re led to the obvious conclusion: P.S. 307 is a failing school while P.S. 8 is a good one.

But this is a deeply misleading picture. Although these scores accurately show disturbing and well-documented achievement gaps in student performance they are incredibly poor measures of school quality, the key reason being that many factors other than schools — such as poverty, racism, and home environments — affect student proficiency rates.

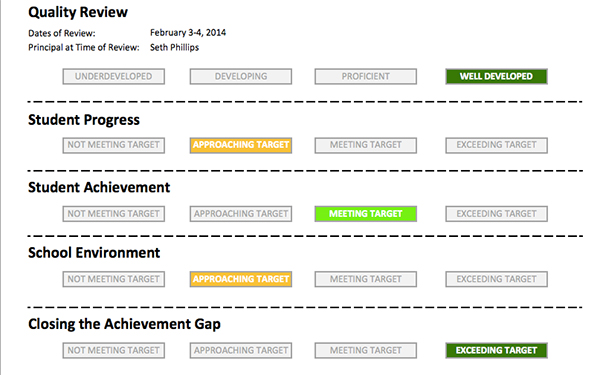

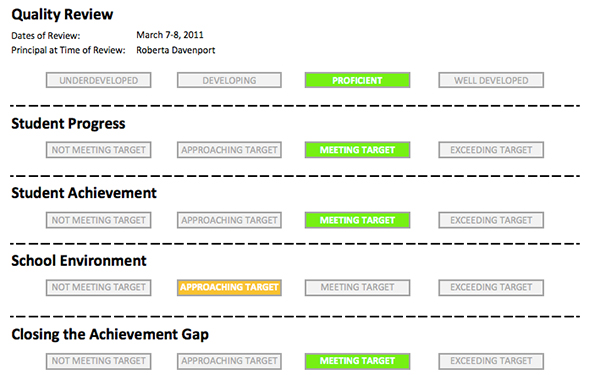

By examining New York City’s school quality guides — which look at a variety of factors including test scores, parent and teacher surveys, and school inspections — there doesn’t appear to be a huge difference between the quality of P.S. 307 and 8. These performance reports are not the be all and end all, but they are much better indicators of school quality than raw proficiency rates.

But wouldn’t you know it, parents don’t seem to care about school performance being properly measured. (This squares with research in Los Angeles.) The Times story reports that one parent calls P.S. 307 “severely underperforming.” Another acknowledges that P.S. 307 is “kind of on the upswing, all things considered,” but asks, “is it at the level of a P.S. 8 yet? It’s not really clear.”

That’s probably because, as Halley Potter, a fellow with the pro-integration Century Foundation, said in an interview, “Families use demographics of schools as a proxy for school quality.” This means that parents assume any school with a lot poor kids or kids of color is a bad one.

Potter says that this assumption is about deep-seated personal prejudices, yes, but it’s also about structural inequity. It is true that in many places schools with lots of poor students get the least qualified teachers, experience significant teacher turnover, and don’t receive an equitable share of resources.

Though according to state reports teachers at P.S. 8 and P.S. 307 have comparable qualifications, experience levels, and teacher attrition rates.

Clearly, it’s inaccurate to assume that the only good schools are in wealthy neighborhoods. Such a presumption leads parents to believe that attending a school like P.S. 307 will harm their child — that’s probably not the case, though, as the performance data show.

In fact, if the school becomes more integrated, all students win, Potter argues. Not only is there research suggesting integration leads to academic gains for low-income students, but middle class students may also benefit, particularly in terms of tolerance and social skills.

One would hope that getting parents more accurate and accessible data about school quality will help them realize as much. After all, it is not surprising that parents pay little attention to data that is complex and opaque, often baffling to even experienced education writers.

But there’s also a more disturbing, but equally plausible explanation for the resistance to integration: Some parents opposed don’t really care about school performance. They may say that their problem with rezoning is based on low test scores at P.S. 307, but in fact, it is possible that no amount of test score data would convince them that sending their kid to P.S. 307 is a good idea.

What they may really oppose, then, is sending their kids to school alongside a large number of poor kids of color. And based on that attitude, it’s hardly surprising that families in P.S. 307 are not welcoming integration either.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)