The Pandemic Set Back Student Learning — But Newark, New Jersey Kept the Data Under Wraps

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

When Newark students took a series of diagnostic tests last fall, some seven months into the pandemic, the results were alarming:

Nearly 80% of third graders and almost 90% of fourth graders would “not meet the passing score” on the state math exams, according to a district analysis that was not made public. The projections suggested that far fewer students were on track to master grade-level math than in previous years.

After a spring of school closures and limited learning, students were seriously struggling in math.

“Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, learning loss among our students in mathematics is one of the most significant challenges faced by schools in Newark,” district officials wrote in an application this January seeking academic recovery funds. “Many of our students have fallen even further behind than they were prior to COVID-19.”

Many of those students likely continued to slip behind last school year as remote learning stretched into April, keeping students out of classrooms for 13 months. Yet, in more than two dozen public school board meetings since the global crisis began, district leaders have never given a detailed accounting of the pandemic’s toll on student learning.

Even after the fall test scores, which the district never publicly released, clearly showed that academic damage had already been done, Superintendent Roger León suggested publicly that learning loss could still be curbed.

“Part of the strategy here is not to assume that there will be loss,” he said at a board meeting in December, “but to assume that we actually can do something about it right now.”

It isn’t just test scores. The district has taken other steps that, intentionally or not, have obscured the pandemic’s full impact on students.

After school buildings shut down last spring and teachers lost touch with many students, the district reported nearly perfect attendance during remote learning. And this past school year, several educators told Chalkbeat they were forbidden from giving failing grades even to students who never attended online class or completed any work — all while the district insisted its normal grading policies remained in effect.

“Their grades aren’t their correct grades,” a district elementary school teacher told Chalkbeat this week, asking to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation. “You couldn’t fail any kids.”

There is no doubt that district officials have closely monitored students’ academic progress over the past year and worked diligently on plans to address their needs. But they have not publicly shared data on student learning or gone into detail about the district’s plans for academic recovery. León has referenced plans for tutoring and Saturday school, but has not disclosed specifics — leaving it unclear how the district will spend more than $40 million in federal money specifically intended to address learning loss.

Newark is not the only school district that hasn’t voluntarily released academic data from the past year. Still, the lack of transparency means Newark families and the public have no way of knowing how far students fell behind during the pandemic, and no way of holding the district accountable for catching them up.

“Until we have the numbers and we own what has happened to our children, we can’t fix it,” said Deborah Smith-Gregory, a former district teacher and president of the Newark NAACP.

Newark community members have repeatedly asked the district for details about the pandemic’s impact on student learning.

At a closed-door meeting in December, school board member A’Dorian Murray-Thomas told district officials that “the board and community want to know more information on how students are performing academically,” according to meeting minutes. An official then gave the committee a presentation on the results of the diagnostic tests students took this fall, called the NWEA MAP Growth tests.

But at a public board meeting the next week, officials said nothing about the tests. When a board member asked León about his plans to address learning loss, he gave only a vague answer. He mentioned “online programs,” “some changes to the curriculum,” and “opportunities before and after school, even on Saturdays.” He did not specify what the programs, curriculum changes, or opportunities were, nor how many students were getting support.

Yet just a month later, in a grant application not available to the public, the district went into detail about students’ academic needs and a proposed program to catch them up.

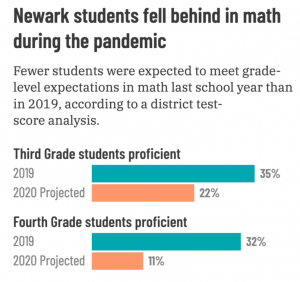

In the application for a state grant to address learning loss, the district revealed that the fall MAP tests showed “students in grades 3 and 4 are struggling in mathematics.” The district estimated that only 22% of third graders would be able to meet grade-level expectations on the state math test, compared with 35% who met expectations in 2019. Among fourth graders, just 11% were projected to meet math expectations, compared with 32% who did so in 2019.

In response, the district proposed a four-week math program this summer targeting 600 rising fourth and fifth graders with the lowest MAP scores. The program would “compensate for the learning loss of the most vulnerable students during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the district wrote in the application submitted this January, which the state would not release to Chalkbeat until June.

The state did not award Newark one of the roughly $156,000 learning loss grants. However, the district is getting more than $282 million in federal pandemic-relief funds, with about $40 million reserved for academic recovery efforts.

Whether Newark is putting any of that money towards an intensive math program this summer is unclear. A district spokesperson did not immediately respond to questions about the program, learning loss data, or recovery plans.

So what is Newark doing to address the unprecedented disruption in student learning, when most students were shut out of classrooms for over a year and many spent part of that time struggling to access online classes?

The district told the state last school year simply that it was offering “Saturday Academies; Extended School Day; Tutoring” to address learning gaps, as well as lessons and counseling to meet students’ social-emotional needs — all services that many schools provided well before the pandemic. The district is also operating a summer learning program, as it does every year. Officials have not described publicly how they modified summer school this year to respond to students’ heightened needs.

Newark is certainly not the only school district in New Jersey, or nationwide, where student learning has suffered over the past year.

An analysis by the New Jersey education department of mid-year test data found that about 37% of students statewide were below grade level in math and English. The analysis also found wide racial gaps, with more than half of Black and Hispanic students below grade level in math, compared with less than 30% of White students.

An independent analysis of test scores from 15 New Jersey districts and charter schools also found evidence of pandemic learning loss. During the first half of last school year, students in grades 3-8 made about 30% less progress in English and 36% less progress in math than they would be expected to make during that period in a typical year, according to the analysis, which was commissioned by the advocacy group JerseyCAN.

Patricia Morgan, the group’s executive director, said officials from the state down to individual districts must be forthright about learning loss before they can properly address it: “We need to know where our students are to get them the resources they need.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)