The Pandemic Forced Millions of Women Out of the Workforce. That’s a Problem Not Only for the Economy, But Their Children’s Lifelong Success

By Debra West | May 17, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

In the early months of the pandemic, Melissa Maniego managed to work from home. Her job as an administrator at a staffing agency gave Maniego the flexibility to help her daughter with remote kindergarten, and her son had not yet started preschool.

By fall it all unraveled.

The job became more demanding, and by then Grace, 7, and James, 3, both needed help with remote schooling. When her company offered a furlough, Maniego, a single mother, took it. Despite a significant drop in income, she didn’t see any other choice.

“Both of my children have IEPs (Individualized Education Programs),” said Maniego, who lives in Fort Lee, New Jersey. “I have to sit next to my son and be his teacher the whole time he’s in class. I have to facilitate things like handwriting or using the screen. He’s in the living room, where I have him set up at his mini-table. My daughter sits at the dining table. They can’t be in the same room, but I have to be within earshot of her so I can hear if she’s tuning out. I have to hear that the teacher is asking her to do things and that she is moving around and doing them.”

As challenging as Maniego’s day-to-day schedule seems, it’s shockingly common in a recession that has disproportionately affected women and put unprecedented strains on working mothers. At a May 7 White House press briefing, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen addressed April’s disappointing jobs numbers, which included more women exiting the labor force completely.

“There are many drivers of these trends … an undeniable one is a lack of support for people as they raise children and care for older relatives,” Yellen said. “Our policymaking has not accounted for the fact that people’s work lives and their personal lives are inextricably linked, and if one suffers, so does the other. The pandemic has made this very clear.”

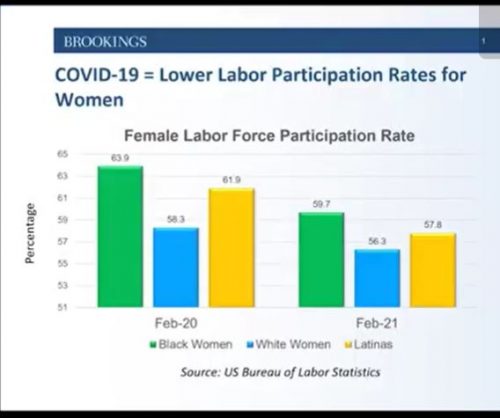

By September 2020, four times as many women as men left the labor force, said Melissa Boteach, vice president of the National Women’s Law Center.

“The net number of women who have left the labor force since the start of the pandemic remains over 2.3 million,” Boteach said in a National Press Foundation forum in March. “This is not evenly distributed. Black and brown women are disproportionately affected. So, nearly 2.1 million women were pushed out in 2020 and the rest this year of the 2.3 million, and of those, 564,000 were Black women and 317,000 were Latinas.”

“We are almost in-waiting to see what the long-term implications are … but it’s not looking good.” —Nicole Smith, chief economist, Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

Parental income and education are leading factors in children’s success, said Nicole Smith, chief economist at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, so women’s job losses, particularly if they are single mothers, is likely to be a determining factor. Black and brown women make up the majority of single mothers.

How mothers’ pandemic job losses will affect children’s lifetime educational attainment is a pressing question.

“We are almost in-waiting to see what the long-term implications are,” Smith said. “It’s really hard to isolate how each of these things is contributing to learning loss. But it’s not looking good.”

One reason for the she-session, as some have called this recession, is the loss of jobs in industries where women dominate, like restaurants, hospitality and retail, Boteach said.

But another, is the overload of having to do it all. The shift to online schooling, the collapse of child care and the impossible demands of being a mother during this pandemic have forced women to give up or lose their jobs.

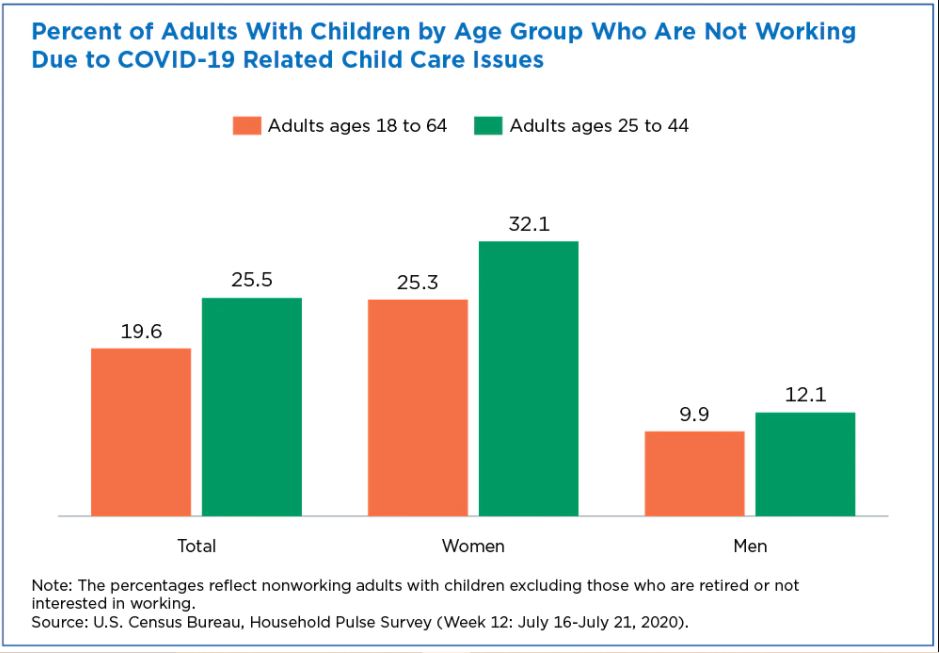

The Census Bureau found that in August 2020, women of childbearing age were almost three times as likely as men to be out of work because of child care demands. A study out of Washington University in St. Louis shows how school closures sidelined mothers’ careers.

At the start of the 2019-20 school year, 18 percent fewer mothers than fathers were working, Caitlyn Collins, assistant professor of sociology and co-author of the study noted. By September 2020, the gender gap widened to 23 percent in states where schools went to mostly remote instruction, but remained close to pre-pandemic rates – 18.4 percent – in states that largely continued in-person learning.

“There was so much stress on the mothers, they end up saying ‘I’m a terrible mother, I’m a terrible worker, I’m no good at any of it.’ —Dawn Meyerski, executive director, Mount Kisco Child Care Center

The Mount Kisco Child Care Center, in the suburbs of New York City, serves 140 children aged 3 months to 11 years old, half of whom receive subsidized tuition. The center barely closed during the pandemic, said Executive Director Dawn Meyerski. First it stayed open for essential workers, but by July the center reopened for all.

“The kids needed to be here,” Meyerski said. “The isolation wasn’t good for them. They needed to be socializing, negotiating, talking with their friends. The parents needed them to be here, too. Can you imagine, even if you work at home, having a 4-year-old at home while you’re trying to work?”

Though she started sending dinners home twice a week as a service for essential workers, Meyerski ended up providing meals for any family that asked.

“We just said, ‘Let’s take the stress off them,’ “ she said. “There was so much stress on the mothers, they end up saying ‘I’m a terrible mother, I’m a terrible worker, I’m no good at any of it.’ I just didn’t want to see anybody go through that stress.”

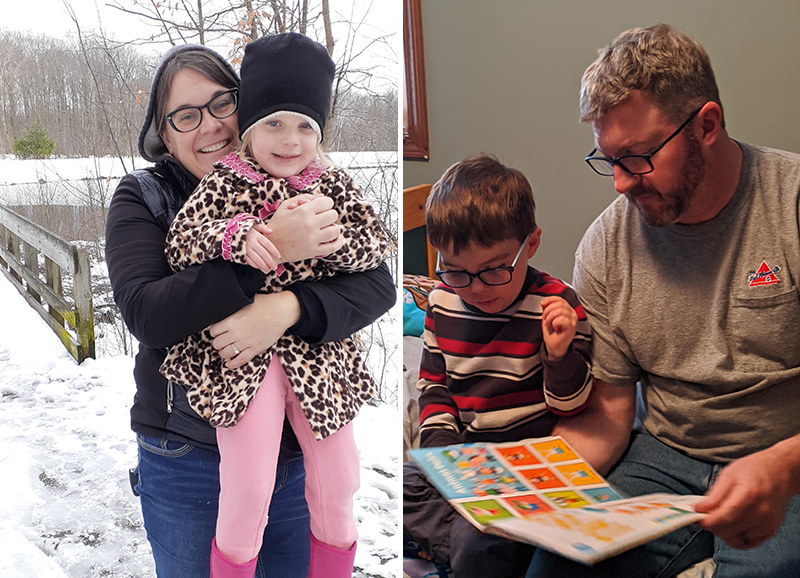

“I told her there was no way I could work with two 3-year-olds climbing over my head. So, I started working a quasi-second shift. I started my day after dinner and worked until 1 or 2 in the morning.” —Virginia Dressler, digital projects librarian, Kent State University

Virginia Dressler, 42, of Newbury, Ohio, learned a thing or two about stress working at home full time while caring for 3-year-old twins during the early months of the pandemic.

“I have a very understanding boss,” said Dressler, a digital projects librarian for Kent State University. “I told her there was no way I could work with two 3-year-olds climbing over my head. So, I started working a quasi-second shift. I started my day after dinner and worked until 1 or 2 in the morning.”

Then, during the day, while her husband, Brandon Hall, was at work, Dressler would switch into classroom mode for twins Winston and Gillian.

“They are at that age where they are sponges,” Dressler said. “When they were home, I tried to make myself into a preschool teacher. There were a lot of programs with the zoo or the library. There were so many options to keep them in this organized mode and that was a real help. I also think it helped that they are twins because there’s a social component.”

By mid-April, her work life got easier, but the family’s financial life got tougher. Dressler’s husband was furloughed from his job as a delivery driver and able to take over child care.

“It’s funny, when my husband was home watching the kids, he was like ‘They’re fine watching PBS. They are 3 years old.’ And at that point I think our whole bandwidth was so stretched that I was OK with it.”

By July, Hall was back at his job and the couple found a small, high-quality preschool program for the twins.

“We were just thankful that we didn’t have to deal with remote school,” Dressler said. “They were young enough that we didn’t feel that they were really missing out, but that’s why we decided to send them to preschool in July. I didn’t want them to miss out any more.”

The relationship between economic stress, or any parental stress, and young children’s development is well documented, said Colin Seeberger, a director of media relations at the Center for American Progress.

“That’s one reason why we’re all so pleased to see the child tax credit, among the rest of the American Rescue Plan,” he said.

The child tax credit, which was expanded to $3,600 for children under age 6 and $3,000 for children under 18 and will be paid in monthly installments during 2021, was intended to alleviate child poverty that stemmed from the pandemic. President Joe Biden is now proposing extending it to 2025 and has put forth a host of other measures under the $1.8 trillion American Family Plan, including $200 billion for free, universal preschool and $225 billion to improve child care.

The earlier child tax credit, along with other stimulus payments, the accelerating rate of vaccinations and business re-openings are credited with a decrease in unemployment in March. Twice as many jobs — 916,000 — were created nationwide in March as in February, the most since August, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the numbers dipped again in April and, according to the National Women’s Law Center, it will take women 28 months to reach their pre-pandemic employment level at the rate jobs were added last month.

We have yet to see what the trend in learning will be, said Smith, the economist at Georgetown University.

“There have been estimates that say kids have lost an entire year despite all the online learning they are trying to do,” Smith said. “Not all individuals are designed to learn online and, for children, the lack of socialization is impacting their mental acuity.”

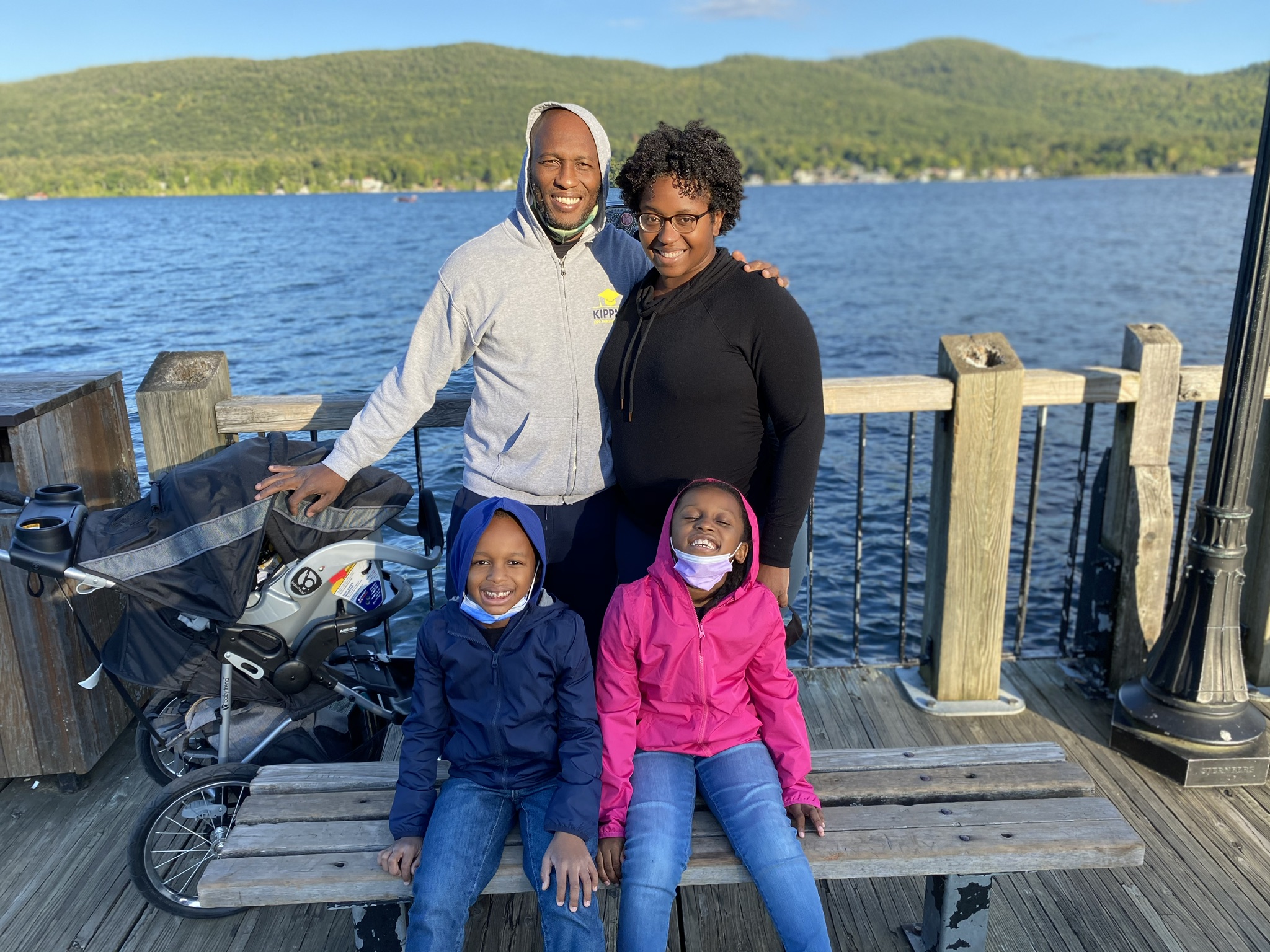

Meredith LeJeune’s work trajectory has followed recent trends. After eight years of building up a public relations business, LeJeune lost 80 percent of her revenue when the pandemic struck.

“My biggest client was in the travel and vacation industry, so that was the first to go,” said LeJeune, who lives in Garnerville, New York. “Their contract happened to be up in March 2020, so they just didn’t renew.”

LeJeune, 38, was expecting a baby that month and her twin first-graders started learning remotely when schools were closed, so having less work was something of a blessing. She was there to help the twins, Addona and Strong, to adjust to online learning. She also had far more time to recover from childbirth and spend with the baby, Mecca, than she did during the single month of family leave she took after the birth of the twins.

Her husband, Ernst, an eighth-grade math teacher at a charter school in Mount Vernon, New York, had been working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the couple normally shares family chores, Meredith’s schedule was more flexible than her husband’s, so she picked up most of the child care.

The North Rockland School District her children attend, just north of New York City, was in hybrid mode until late April, when the children went back full time. That meant LeJeune’s twins were at home until lunch and attended in-person school after noon only for most of the year, which translated into very long hours for her.

“The pandemic brings in more chaos in the morning,” LeJeune said, before school resumed in person. “Some days could be very smooth, while others are frantic. Prior to the pandemic they were in school all day. I would help them get ready in the morning, and then by 9 a.m. they were out of the house. Now, since the kids are home until noon, my workday doesn’t really start until about 1 p.m. I can be working all through the night. I sometimes don’t get to bed until 2 or 3 a.m.”

Some of the stress eased when her children went back to school, and seem to be doing well.

“It worked out,” she said and in February, LeJeune signed a few new clients and got several freelance assignments.

Maniego is still months away from a return to normal. The Fort Lee school district had offered hybrid learning for children with special needs, but Maniego was worried about the virus and the school’s frequent quarantines and decided remote schooling was the better option.

Now she has to wait until the new school year begins to enroll them. Still, she’s planning to send the children to day care over the summer so that she can return to work.

“I miss working,” she said. “I hope I still have a job to go back to. If not, I don’t know what I’ll do.”

Lead Image: New Jersey mother Melissa Maniego at home this winter with her two children, Grace, 7, and James, 3. (Melissa Maniego)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter