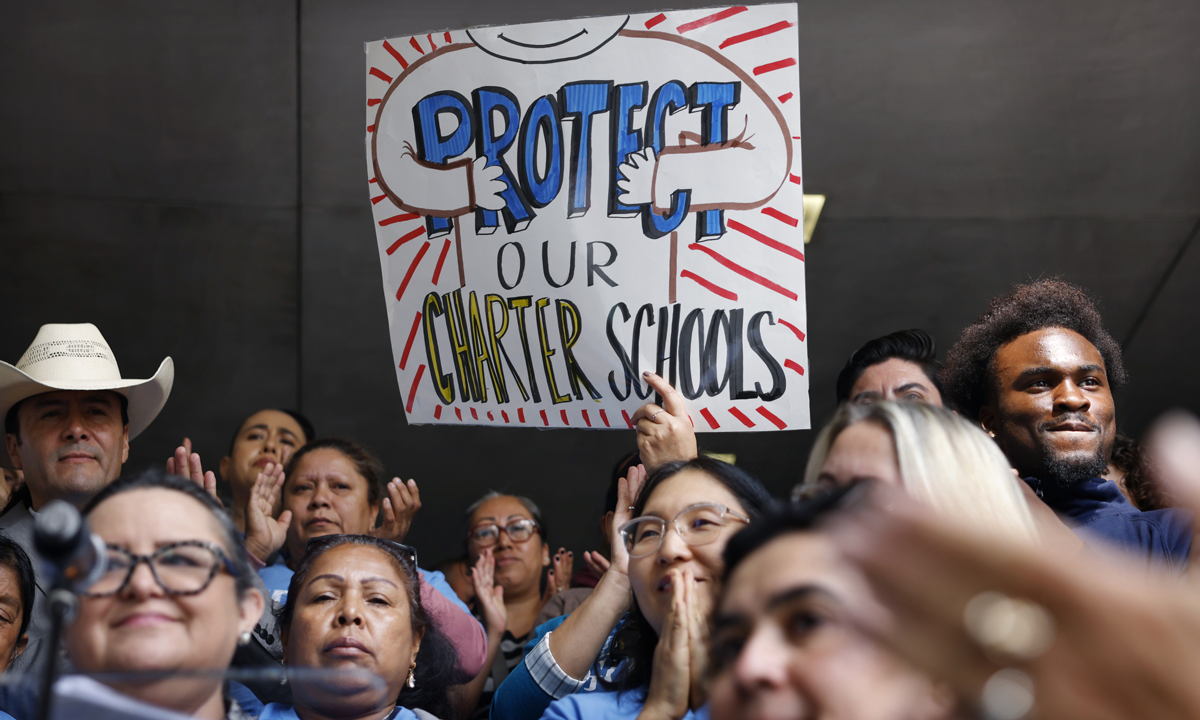

The Nation’s Biggest Charter School System Is Under Fire in Los Angeles

From enrollment declines to new policies governing approvals, renewals and real estate, California’s charter operators say they’re fighting to survive

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The nation’s largest experiment with charter schools is no longer growing. These days, Los Angeles charter leaders say their schools are just trying to survive.

With tough, new policies, falling enrollment, and a hostile district school board, the decades-old charter school sector in Los Angeles has never faced headwinds so stiff, operators say.

Los Angeles, which has more kids in charter schools than any city in the country, this month banned charters from nearly half its school buildings, even as dropping enrollment emptied out classrooms across the city.

Enrollment is cratering for schools across Los Angeles, with district schools seeing larger drops than charters.

Later this year, L.A. is bringing its charter renewal process back online after a three year suspension due to the pandemic, employing a state law meant to hasten the closure of low-performing charter schools.

And fewer kids are signing up. Applications for opening new charter schools in the city, which once arrived annually by the dozen to L.A. Unified, this year completely dried up, according to the California Charter Schools Association.

One of the largest charter networks in Los Angeles, KIPP SoCal Public Schools, is closing three campuses this year due to declining admissions.

“We’re on the brink of a new chapter,” said Joanna Belcher, chief impact officer for KIPP SoCal, which currently operates 23 charter schools.

“In L.A., specifically related to ed reform, for a long time, the focus was on growth,” said Belcher. “But now, particularly in L.A., our focus is not on growing.”

Instead, Belcher said, the network is focused on making sure existing schools can continue to operate, and deliver on their promise of providing high-quality options for families in need of good schools.

To accomplish those goals, Belcher said, KIPP SoCal is working to hasten post-COVID academic recovery, attract and retain talented staff and refine its teaching practices based on feedback from graduates.

Charter schools now account for about 20% of the district’s enrollment, serving more than 150,000 students in kindergarten through 12th grade in 275 schools.

Enrollment in the schools peaked in 2021, when the city’s charters enrolled nearly 168,000 students. Since then admissions have declined by nearly 11%, although not as fast as district schools.

L.A. Unified enrollment reached 639,337 in the 2015-2016 school year and fell to just 538,295 in 2023, a decline of nearly 16%.

Experts say reasons for declining enrollment in Los Angeles include a falling birth rate, families leaving the city, and more families choosing homeschools.

The shuttering KIPP schools aren’t the first charter schools in Los Angeles to close in recent years. More than a dozen other charters have shut down in the city since 2019, with falling enrollment being a chief reason for the closures.

Declining admission is being felt across the city. With vastly more resources than the independently run charters, L.A. Unified has so far avoided the closure of traditional public schools, although Superintendent Alberto Carvalho recently said it is a possibility.

Keith Dell’Aquila, vice president of greater Los Angeles local advocacy for the California Charter Schools Association, said the district’s new colocation policy, which blocks charters from many of the city’s campuses, has also discouraged new schools from opening in the L.A. Unified.

“Our expectation is for the district to treat charter school students and their families fairly,” Dell’Aquila. “We absolutely do not believe this policy reaches that standard.”

This year, there are zero petitions to open new charter schools in the district, Dell’Aquila said.

It wasn’t always this way.

L.A. Unified, the nation’s second largest district, was one of the first in the country to allow charter schools, converting its first school to charter status in Westchester nearly 31 years ago.

A period of rapid growth for charters in the district commenced, with enrollments peaking during the pandemic. There are still more than double the number of charters in L.A. Unified than there were a decade ago.

But though the district’s charters outperform traditional public schools on state tests and post higher graduation rates, charter operators feel they are under attack, said Oliver Sicat, CEO of Ednovate, which has five charter high schools in Los Angeles.

“It’s the low point now,” said Sicat, who has operated charters in L.A. for a dozen years, following stints as an educator and administrator in Boston and Chicago.

The district’s enthusiasm for charters, Sicat said, has journeyed through peaks and valleys over time, but in recent years a shrinking pool of students has come to pit district schools against charters. Both types of schools are funded on a per-pupil basis.

“It’s gone from an atmosphere of collaboration to one of competition,” said Sicat.

Two years ago elections to the LA school board tipped, giving the board a new majority with a skeptical take on charter schools, and handing opponents of the schools, who argue charters siphon resources from district programs, a powerful upper hand.

The board in September issued a new resolution for Carvalho to create a policy banning charter schools from collocations at roughly 350 school buildings, and barring charters at collocated sites that could disrupt enrollment feeder patterns for district-run schools.

Carvalho complied, and at a Feb.12 meeting the board voted 4-3 to approve the union-backed colocation rules. Board president Jackie Goldberg, a coauthor of the resolution calling for the policy, said the policy is meant to preserve district programs.

“The whole point of charter schools was not to replace the public schools, but to improve the public schools,” she said. “That has been lost, as soon as you make it a competition.”

With the board’s majority tilting against them, charters could be closed down in the upcoming cycle for renewals, which the schools face this year for the first time since 2020, said Joni Angel, executive director of the Los Angeles Coalition for Excellent Public Schools, a group that a represents some of the city’s largest charter operators.

“It feels inevitable, at this point, that charters will close,” Angel said, both due to the new colocation policy and renewal cycle restarting, given the current composition of the board.

But Angel said the board could tip again back in charters’ favor in the coming November elections. Two incumbents are running for reelection and two retiring members, including Goldberg, are leaving open seats.

If either of those open seats is won by a pro-charter candidate, the board’s current majority could flip, Angel said.

Fraught school-board races are nothing new in Los Angeles, where for years both unions and charter school backers have thrown their might behind candidates to win elections that could tilt the board in either direction of pro- or anti-charter.

Gregory McGinity, executive director of the California Charter Schools Association Advocates, said the pro-charter group, which has backed candidates in the past, is keeping a close eye on the upcoming school board races, for which primaries will be held next month.

“We believe that voters will respond positively to candidates who champion policies that foster collaboration between traditional public schools and charter public schools,” McGinity said.

With the California Charter School Association already threatening legal action against L.A. Unified’s new collocation rules, and the upcoming school board elections, conditions in the country’s largest charter school system could again favor charters, said Morgan Polikoff, an associate professor of education at the University of Southern California Rossier.

“It’s not really clear to me what’s likely to happen in this election. But absolutely, if the board changes hands, that could have a serious impact,” he said.

California Charter Schools Association President Myrna Castrejón said for now the future of charter schooling remains unclear in Los Angeles, and, indeed, all of California, where statewide enrollment in charters reached a peak about three years ago.

“The value of charter schools in the next ten years is going to be defined less by how fast you can grow, but how responsive you are to change,” Castrejón said. “We see families leaving the public school system, period, in much higher numbers than we ever have before.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)