The Milwaukee GOP Debate: In the Birthplace of School Choice, Will Free Market Talk Extend to K-12?

Polly Williams was fed up with the Milwaukee Public Schools. Because less than 60 percent of its students graduated in the late ’80s, Williams, a mother of four and a Democratic state representative, was convinced that public education was failing low-income black children — and she had an idea for how to fix it.

Give poor families, she pitched, a publicly funded voucher to pay for private school.

Twenty-five years after Milwaukee became the birthplace of the private school choice movement, Republican presidential candidates will gather there Tuesday night for their fourth debate. But it’s questionable whether that element of school reform and its long history in Milwaukee will rise to the surface in a forum whose focus is the economy.

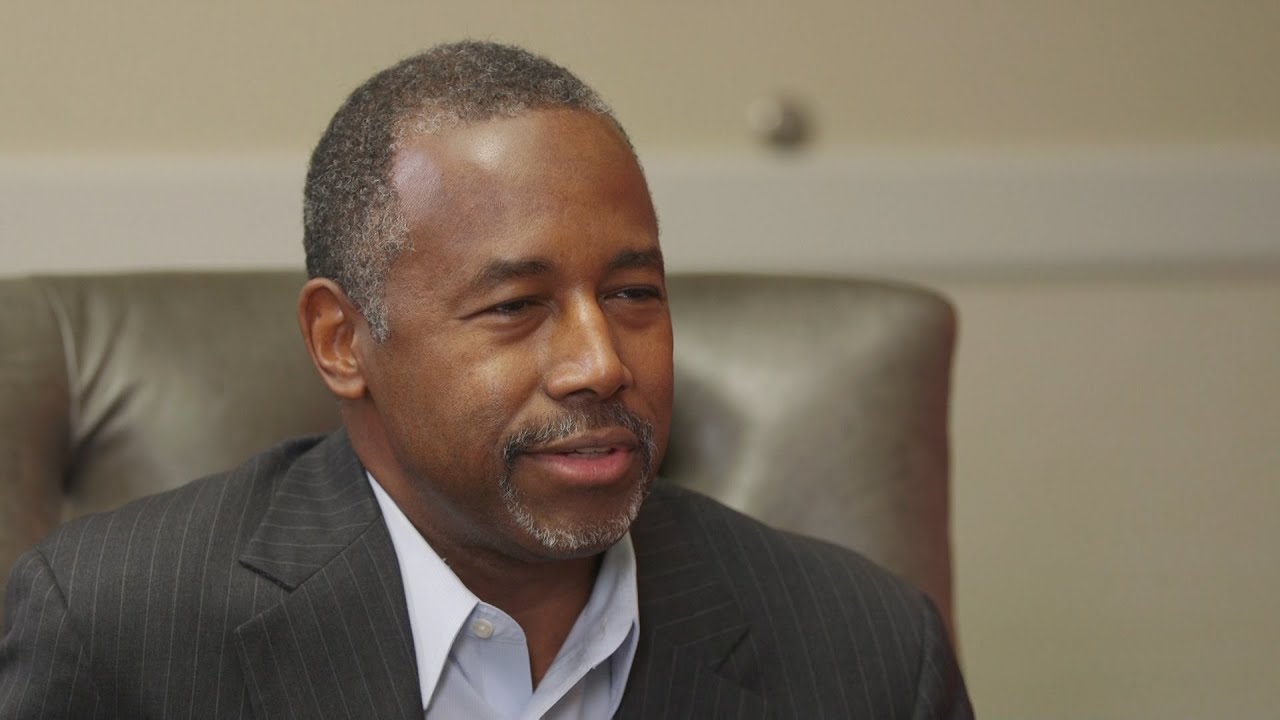

VIDEO: Dr. Ben Carson Talks With The 74 in Milwaukee Ahead of Debate Night

Free-market economist Milton Friedman, along with conservatives and other libertarians, was among the earliest supporters of the idea, which until then had not been implemented anywhere else in the country.

It came to Milwaukee after Williams and Howard Fuller, a local activist who would later become superintendent of the Milwaukee Public Schools, failed to garner support for their efforts to create a separate school district within the city, one that would almost exclusively serve black students.

“If you’re not going to educate our kids [and] you won’t let us create our own district — give us a way out,” Fuller explained in an interview with The Seventy Four.

That way out was the voucher bill that Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson signed alongside Williams in 1990 despite stiff opposition from the teachers union and the local NAACP.

“Monopolies just don’t seem to work,” Thompson said at the time. “A modified choice program is going to give people a choice, especially poor people who are locked into a school district that they have no opportunity to decide if that’s a good school district for their sons and daughters.”

Williams, who was featured prominently in a 1991 “60 Minutes” segment lauding the school choice initiative, threw down an even more ambitious gauntlet.

"We're now going to show that our children can be educated successfully for less than half the money that the Milwaukee schools use to miseducate our students," she said.

The program started with just a handful of schools and about 1,000 students, but expanded over the next few decades, particularly after the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in 1998 that it was constitutional for vouchers to flow to religious schools.

Today, 114 private schools, the vast majority religious, and 26,000 Milwaukee students participate in the voucher program — about one-third as large as the approximately 75,000 students enrolled in the city’s public schools.

“The Sky's Not Falling but Neither Is Manna”

In 1990, political scientists Terry Moe and John Chubb declared that school choice “is a panacea.” No fair accounting of vouchers in Milwaukee, however, suggests that this hope came to pass. As the headline to a 1995 New York Times article put it, “the Sky's Not Falling but Neither Is Manna.”

Initial studies found voucher recipients doing no better, and sometimes worse, than public school students. Recent research has painted a more positive picture, though, finding that enrollees in schools that received vouchers were more likely than demographically similar public school students to graduate high school, and enroll and remain in college. Voucher students had similar achievement gains in math but modestly higher gains in reading. Competition from private schools may have spurred small improvements in Milwaukee Public Schools, but those gains appear to have leveled off after just a few years.

Other research found that a large number of students who enrolled in private schools with vouchers subsequently returned to public schools — and realized large achievement gains upon doing so.

Fuller for his part said the program had been successful in creating options for families who previously lacked them, but had not focused enough on ensuring that all schools of choice were good schools.

“There’s a value to providing people with power so they can choose, but I think the ultimate objective is to make sure people can choose quality options,” he said.

Fuller backed changes to the program in 2009 to increase transparency and accountability.

From social justice vouchers to middle class subsidies

When originally pitched in the Wisconsin legislature, vouchers were designed to help low-income students afford the private school tuition that many middle- and upper-income families were already paying.

But to many school choice proponents, that was not enough. Republicans in Wisconsin, led by Gov. Scott Walker, have successfully expanded vouchers to include middle-class families, as well as schools outside of Milwaukee.

“Our goal should be to provide as many quality educational choices for parents as possible,” Walker has said.

And yet some voucher supporters say this is a bridge too far. Walker, who was still in the Republican race for president at the time, praised Fuller at The Seventy Four’s education forum in August. Fuller quickly distanced himself on Twitter, saying he opposed Walker’s push for universal vouchers.

In a 2011 op-ed, Fuller argued that Walker’s plan to lift income restrictions “would dramatically change the program's social justice mission and destroy its trailblazing legacy.”

Fuller this week said he saw this split coming.

“I was in rooms with people who would say, ‘I’m in this because I really believe in universal vouchers, I’m going to support low-income [vouchers] for right now, but if I ever get to the point where we can go universal, this is what we want to do.’ And every time it was said in my presence, I said, ‘And when you all do, I will oppose it.’”

Polly Williams, who died a year ago Monday, felt similarly, fighting Republicans’ attempts to expand vouchers in 2013.

“They have hijacked the program,” she said.

But Fuller, who had worked alongside Williams for decades, said it was she who ultimately saved the Milwaukee voucher system from being dismantled. He said in 2009 there was talk among Democrats of trying to eliminate the program, but black elected officials from Milwaukee, including Williams, fought successfully to protect it.

“If Polly had said, ‘I’m not going to support it,’” Fuller recalled, “ it would have been very difficult to sustain the program.”

Photo by Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)