The Important Lessons We Can Learn from Rural Schools

McKenzie and Walsh: Rural schools are finding ways to reflect a diversity of viewpoints even in homogenous communities.

Throughout 2025, the George W. Bush Institute will explore the nature of pluralism and how it’s working in our country. This essay was originally published by The George W. Bush Institute. It has been edited for length and style by The 74.

On any given Wednesday, all 370 students from the junior and senior high school in Union City, Indiana, break into teams to address one aspect of their hometown’s needs. One group heads out to work on improving their city’s park and playground. Another serves in an animal shelter. A third visits elderly residents in a nursing home.

The students may operate in teams, but those we spoke with consider Workforce Wednesday one big project. “Wednesday was my favorite day,” one student told us via Zoom. “Workforce Wednesday gets us out into the community,” said another. “Teamwork is what we do best.” As one teacher said, “We show up for each other.”

Shared projects create community

The Union City effort is just one example of community projects binding people together in rural schools. We spent the past few months interviewing rural students, learning how their schools are building a sense of belonging and functioning as community hubs. We also explored ways that these rural schools are promoting pluralism and a diversity of viewpoints even in homogenous communities.

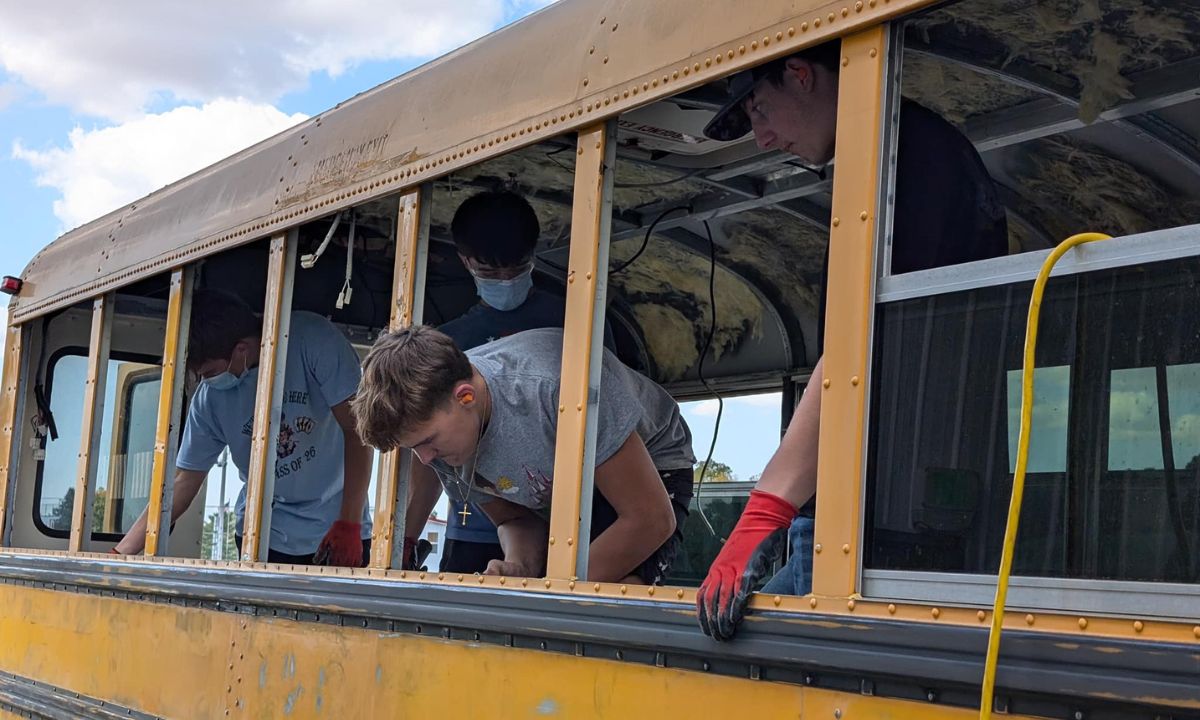

Service projects represent a powerful way to strengthen the social tolerance in these communities. It allows people to work together despite their differences. “Workforce Wednesday lifts each other up and lets students get dirty while they do it,” one teacher said.

In Milano, Texas, 70 miles northeast of Austin, we found high school students working together similarly. Every Friday, members of Family Career and Community Leaders of America provide food to kids in need. Other students host coat drives. Some students helped families devastated by a shooting in nearby Rockdale. One dressed up in a festive costume to entertain the kids along the sheriff’s big Christmas parade route.

“I like to help people,” one Milano student related. “Picking up trash on the road makes you feel you can do more.”

Several cited the town’s role in pushing students to do more. “The community helps us help others,” one said. “They get us to try harder.”

Students in each rural school we visited emphasized how everyone needs to pitch in at school or things don’t get done. Unlike on big urban or suburban campuses, everyone in a rural school must participate, or a sport doesn’t get played, a concert doesn’t get conducted, a school play goes unperformed, a community project doesn’t get done. You could call it multitasking on steroids, but the need for all to lock arms breeds relationships.

“We depend upon one another,” said one teacher. “This is all we have.”

Not that everything is done perfectly. It isn’t. Nor must students have all the right skills. “You don’t have to be excellent to participate,” one student told us. But activities don’t occur, and needs don’t get met, unless people step forward in rural schools.

The lesson is to find projects that bring together volunteers from different backgrounds. Think of it as a social investment that pays dividends in the form of building trust, developing friendships, and providing purpose. Not only does such work address a community’s need, but it creates bonds with others who may see the world differently. We then can start having the kinds of conversations that help us better understand each other. Importantly, we start seeing each other as friends or neighbors, not as “the other.”

Taking advantage of a small size and common identity

A second significant lesson from rural schools is that breaking groups down into manageable sizes makes it easier to “practice pluralism.” It’s much easier, after all, to get to know and understand others in a workplace with only a few dozen people, an intimate house of worship, a small school, or a neighborhood association rather than in, say, a massive lecture hall, a large corporate setting, or even on the wide-open internet.

The sheer proximity of people to each other breaks down barriers in places like Marfa, Texas, which sits about 60 miles from the U.S. border with Mexico. “We are so small,” one Marfa administrator told us about her district’s 58-student high school, “students have to see everyone. You can’t ignore your ex-boyfriend walking down the hall.”

True, such settings can breed drama, as one teacher told us. That’s an unavoidable part of human nature. But that can’t last too long in a small setting. “Everybody knows everybody, so you have to come to terms,” the administrator explained.

What we heard from students as well as administrators is that the small size of their schools and communities creates a sense of belonging. “The small community culture takes on a bigger purpose,” one administrator told us in Thrall, Texas, which sits northeast of Austin. “Every member counts.”

The challenge, though, is to create a sense of belonging for those who feel like outsiders. Thrall ISD, which serves about 800 students, holds a “New Tiger” night for students and parents entering the district. They learn about the history of the town and about traditions such as the community’s harvest festival. The district also offers “Thrall dogs,” special hot dogs, on those nights as a way to celebrate the town and create a common identity.

Marfa ISD, which consists of two campuses that together serve students from elementary school through 12th grade, is somewhat unique in that the ranching and farming community became an arts destination when the late artist Donald Judd set up shop in the far-flung West Texas town in the 1970s. His high-concept, minimalist art became a destination for artists and their patrons. Today, Marfa combines a creative class of artists and writers with residents who, in some cases, have worked the land for generations — or who come from Mexico to work each day.

This duality has created what some students described as two Marfas. Tourists and newcomers may stroll through the galleries, but students do not necessarily visit them. As a result, the small community has had to be intentional in building bridges.

That includes events like the annual Marfa Lights Festival and Labor Day pageant. Marfa’s high school’s volleyball games also bring residents together, as do churches and youth religious organizations like Young Life. We also found that some students bonded over interests in agriculture and rural life: raising livestock, fishing, and hunting. One described a rural ethic of commitment to work.

A common identity can be a two-edged sword. Too much homogeneity can create a chilling effect where some issues don’t come to the surface or people don’t express their true feelings. But a shared identity can benefit a group in other ways, such as providing a common set of values. Debate about different topics can take place more easily within that context. Knowing that you share common values helps people disagree about some topics in a more respectful way. After all, you may know your neighbor in a way you don’t know someone living far away. As one educator in Union City put it: “I have never met a president, but I know my neighbor’s needs.”

The lesson here is to start small in building relationships, use shared beliefs to engage in difficult conversations, and welcome the outsider.

Schools as a community hub

About 760 of Texas’ 1,200 school districts have fewer than 1,500 students, according to the Texas Association of Rural Schools. Not all of those districts qualify as rural in the traditional meaning of small towns and open lands. But many do, and each district is woven into the fabric of the community. “The school is the community,” says Randy Willis, executive director of the Texas Association of Rural Schools. The school district often is the biggest institution in town.

We found schools to be the hub of the communities we studied. For one thing, campuses are the source of entertainment. Sporting events. Music and theater performances. Festivals like the Marfa Lights. “School activities drive the culture,” explains Willis, who previously led Granger ISD in Central Texas.

Schools also bring together the larger community for other reasons. Thrall ISD recently hosted a memorial service on its football field for a former student who died while attending the U.S. Air Force Academy. “Make schools a second home,” a Thrall teacher said.

The teacher/student relationship also plays a role in schools serving as a community hub. In our interviews, teachers described knowing kids personally. This helps them hold those students accountable if they start causing trouble. “We only have one hallway,” a Milano teacher smiled as she made the point about knowing what might be going on with students.

That makes it easier for teachers to forge common ground among students. “It’s the skill of the teacher to bridge differences,” Willis told us. “Managing nuances is the art of teaching.”

Ironically, avoiding insularity may be easier in small settings. Principals and teachers, even superintendents, know where students live. They may know their parents. Or see the student in stores. Maybe even teach them in Sunday school.

This interaction creates a relationship that transcends the classroom. When the relationships work well, teachers can help all students feel a sense of belonging. “The staff is devoted to helping young people develop civic responsibility,” a veteran Milano ISD teacher told us. “We jump on kids if they go after another person.”

That level of accountability, along with the visibility it provides, can help develop the character of students and inspire them to be better citizens for the community. This doesn’t have to be limited to small, rural districts. One educator told us some mega-Texas high schools are trying to replicate the same environment.

Let us hope they do.

Yes, differences exist

We’re not trying to create some idyllic, romanticized picture of rural schools. Differences exist, just like they do elsewhere.

One teacher said it was hard to find common ground among adults in his community. And, among kids, their adolescent anger can make finding common ground difficult. “Kids can be brutal,” the educator said.

Students in Milano said they don’t like when someone pushes an agenda on them.

We also heard from teachers across the districts about how social media makes it harder to break down siloes or get students’ attention. “Social media is about promoting yourself,” one Milano teacher lamented.

Here’s another challenge: In a place like Marfa, where separate cultures exist, students and adults can feel like they live in between cultures. In small towns with a homogenous population, people may keep things to themselves out of fear of upsetting the peace. “It’s harder to stick out,” said one student of her district.

Still, despite the differences they encounter, rural schools can and do “practice pluralism” allowing for a diversity of viewpoints. An Indiana teacher told us that people find a middle ground when they approach an issue with an open mind. “Voice your opinion, but don’t attack each other,” one Union City student emphasized, capturing the essence of pluralism.

In Milano, all heads nodded when we asked if differences exist. Yet students talked about how conversations help them understand how others think. “We had a respectful debate about abortion,” another reported. One concluded that he would rather win a baseball game than an argument.

In essence, relationships matter.

Practicing pluralism can be particularly challenging in homogenous communities, where there can be tension between beliefs and institutions that form character versus forces that push people into going along to get along. Navigating this tension is why we need a pluralistic society, and that is no different for rural schools. As Randy Willis says, each district is a microcosm that requires managing conflict.

The lessons we have learned include understanding that some level of homogeneity can be positive, allowing for a common purpose or mission to develop. That could take the form of values like those laid out in America’s founding documents, a unifying project, or even adversity.

We’ve seen this idea repeatedly as we write for the Pluralism Challenge. For example, in our essay, “Making space for different faiths is important in a strong democracy,” we described how the Dallas-Fort Worth Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council finds shared struggle in fighting against bigotry committed against their respective faiths.

We recounted various festivals, sporting events, community service organizations, local rituals, and simply the daily interactions and routines of attending school in rural towns. These social touchpoints welcome people into the community as well as contribute to a sense of belonging. That in turn fosters the relationships and community trust that creates a small town “e pluribus unum” effect.

However, too much homogeneity can suffocate the practice of pluralism with its pressure to “go along, to get along.” Why rock the boat by offering a different point of view or argument if it only disrupts social harmony?

If that mindset solidifies broadly within the community, the proximity, accountability, and visibility in these rural communities could morph from curbing bad behavior to coercive peer pressure. This could stifle the free flow of ideas, disagreement, or even the ability to hold different identities simultaneously.

In one town we heard how these negative aspects were perhaps manifested in an unexpected way. Teachers shared with us that they overheard some students made insensitive remarks about a particular ethnic group in front of friends who were of that ethnicity. When confronted by teachers, the offending students seemed genuinely confused. They suggested that they weren’t referring to their friends because they were “one of us.” And their friends denied being offended or targeted by the remarks.

Was that really the case or were they going along to get along? We don’t know, but it’s easy to imagine how one might be hesitant to disrupt social peace or call out a friend.

The big takeaway is that practicing pluralism requires balancing homogeneity with the ability to express opposing views or maintain different identities while remaining connected with the community. Admittedly, that line may not always be clear or universally applicable. In true pluralistic fashion, communities themselves are responsible for defining what norms are acceptable and how to enforce them.

Practically, though, it’s helpful to have local processes, forums, or institutions –- like town hall meetings, school boards, local newspapers, classroom debates, and clubs –- where people feel comfortable arguing ideas or maintaining different identities. At the very least, these things can be a bulwark against groupthink.

Conflict can be managed when people in a community are intentional about putting these points into practice. Once they do, they can start having those difficult conversations that explore the differences people have about politics, culture, religion, or any other potential points of division. This isn’t always easy to do.

Perhaps, though, we can draw inspiration from these rural communities that seem to be fine-tuning that balance between homogeneity and individuality. This is encouraging at a time when many Americans seem bitterly divided over national politics or culture war issues. Those in larger urban areas across the United States should find ways to replicate the positive rural-town practices and institutions that are fostering a greater sense of belonging, citizenship, and purpose.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)