A Grand NCLB Compromise Takes Shape, as Conference Rewrite Chips Away at Federal Accountability

An aging British rock star is an unlikely spokesman for congressional compromise.

And yet Mick Jagger and The Rolling Stones’ lyric “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you need” was a common refrain at Wednesday’s first conference committee meeting to finally rewrite No Child Left Behind. The gathering is aimed at hammering out differences between the House and Senate versions of the country’s K-12 education law.

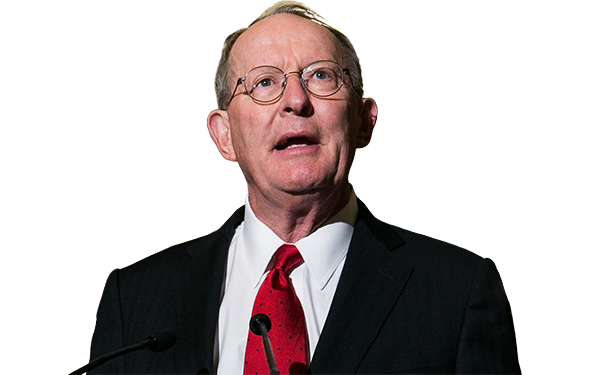

Sen. Lamar Alexander, the chairman of the Senate education committee, kicked off the day by noting that he didn’t get everything he wanted — particularly in the area of school choice — but will back the compromise nonetheless.

“I have decided, like a president named Reagan once advised, that I will take 80 percent of what I want and fight for the other 20 percent on another day,” he said.

A summary of details, provided by the education committees late Wednesday, reveals Democrats got what they needed, if not what they wanted, on accountability and early childhood education, while Republicans’ desires were mostly met in the areas of school choice and program consolidation.

The compromise will be considered for amendment at a meeting Thursday morning with the goal of a delivering a bill for Obama’s signature by the end of the year.

Without some clear accountability measures preserved, the bill would have been seen as a non-starter for the president. The compromise version require states to intervene in schools where fewer than two-thirds of students graduate, the bottom 5 percent of schools, and schools with large achievement gaps. Each state, though, will design its own specific accountability systems, which can include metrics other than test scores, and decide how it will move to fix those low-performing schools.

Rep. Susan Davis, Democrat of California, said the accountability provisions aren’t as strong as civil rights groups, and she and other congressional Democrats, would like to see, but the measure will go a long way towards ensuring that students in failing schools are not simply ignored.

Senators Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who co-sponsored an amendment in the Senate to include those requirements, both seemed cautiously optimistic that accountability wasn’t wiped out altogether. They both voted against the final bill in July when their amendment wasn’t adopted.

Murphy said it isn’t worth recrafting the Bush-era’s No Child Left Behind law if it isn’t also a civil rights bill that keeps within its sights the achievement gap between white, affluent and middle-class students and students of color, those who are poor, disabled and English language learners. Congress must set high expectations for all students, particularly those that have often been ill-served by the school system, without being overly prescriptive to the states. The bill strikes that balance, he said.

Warren called the compromise a “significant improvement” over what the Senate passed.

Democrats also touted the inclusion of language that authorizes the Preschool Development Grant, a partnership between the Education and Health and Human Services departments that aids state creation and expansion of preschool programs for four-year-olds from low-income families. Congress has given $500 million for the program over two years without specific legislative language authorizing it.

Sen. Mike Enzi of Wyoming, meanwhile, criticized the creation of a new program. Republicans often point to a report by the Government Accountability Office that tallied more than 40 federal programs that fund early learning. (Democrats note that the GAO’s count includes both traditional preschool programs and other initiatives, things as varied as school lunches, or assistance for domestic abuse victims, whose purpose goes beyond just early learning.)

“I do not think the federal government has made the solid effort to consolidate the over 40 funding streams for early childhood education,” Enzi said.

Republicans, meanwhile, had to compromise in two of the areas in their “win” column.

The bill wouldn’t allow Title I funds to follow poor children as they move among public and charter schools, a component of the House measure and one of Alexander’s priorities. It would, though, boost the federal charter and magnet school programs that offer school choice.

Rep. Luke Messer, who introduced an amendment in committee to allow Title I funds to go to private schools, as well as public and charter schools, said the bill is a good start.

“I am an unapologetic champion of choice in education in America, and I believe we cannot rest as a nation until every family and every child has the opportunity to go to a great school,” he said. The compromise “won’t quite allow us to promise that, but it is a major step in the right direction,” he said.

The compromise allows investment in new charter school models as well as the replication of existing proven high-quality models, according to the committees’ summary.

Republicans also didn’t get to consolidate quite as many free-standing federal programs into one large block grant as they’d like. The original House bill consolidated about 70; the compromise combines about 50, Rep. Todd Rokita said during Wednesday’s meeting.

The new program, the Student Support and Academic Enrichment grant, will divide the federal money based both on a state’s population and need, according to Rep. Marcia Fudge, Democrat of Ohio.

Separate grants remain for innovation, teacher quality, STEM education, afterschool programs, literacy, arts education, community involvement in schools, student health and safety and other “bipartisan priorities,” according to the committees’ summary.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)