This piece was published in partnership with The Atlantic

(Five Points, California) — It’s 7:50 on a hot, dry August morning when the buses rumble past a barren field — normally filled with broccoli this time of year — and creak to a stop in front of a one-story school, dust blooming up from under their wheels.

Children spill out, the older ones eager to greet familiar teachers. Parents and shy kindergartners congregate around the superintendent and principal, Baldomero Hernandez, who pats shoulders and shakes hands, bending down to welcome the smallest students, like a pastor whose flock has finally returned.

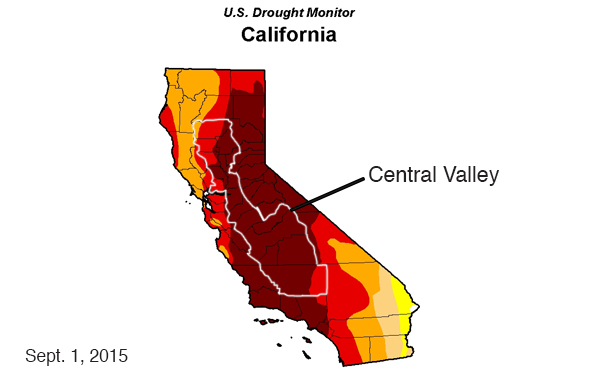

It’s the first day of school at Westside Elementary and Hernandez counts fewer kids than ever climbing off the buses. The buzz of “Buenos dias” and “Como estas?” breaks the yawning stillness that has settled in this stretch of dusty farming country in the San Joaquin Valley. The 27,000-square-mile region stretches from Sacramento to Bakersfield and lies within the larger Central Valley, the epicenter of California’s four-year drought.

If the drought persists, Hernandez knows that some of his students — mostly poor, Hispanic children whose immigrant parents work the land — won’t stay through the end of the year. Many of the youngest ones, he worries, won't be around to graduate from eighth grade and go on to a nearby feeder high school. As crops dry up, families are forced to move in search of jobs and housing. Families who do choose to stay double up in cramped bedrooms or sleep on couches in relatives’ homes, praying for rain and a return to work.

“Drought is like a cancer,” Hernandez tells me. “It kills you slowly.”

Enrollment in his tiny district is down 14 percent from four years ago, to 230 students, which translates into hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost state aid — on top of years of funding cutbacks statewide. Similar double-digit enrollment declines can be found in other small, rural school districts throughout the valley, including the Pleasant View school district in Tulare County, where more than half the migrant student population has left in only three years. Overall enrollment is down at least 17 percent since 2011.

The Firebaugh-Las Deltas Unified, further north, has lost 120 of its 2,400 students in the last two years, largely due to parents’ job moves.

In larger districts where enrollment hasn’t yet changed dramatically, educators say they are starting to brace for the worst. If an El Nino doesn’t drench the region this winter (which could set off a host of separate problems, like flooding and mudslides) they expect to see families leave en masse for Sacramento, Washington, Oregon, or return to Mexico.

Beyond the slow-motion emigration, the daily routines of the students, teachers and staff who remain have been upended. In Pleasant View, the superintendent spent all spring and summer doubling as a construction manager, overseeing the drilling of a new well so his school would have a reliable water source.

A school in East Porterville, one of the most deeply affected areas in the state, now offers daily showers and bottled water for students without running water at home. Teachers are on constant alert for pupils who’ve lost focus and confidence; they’re humiliated to be wearing dirty clothes in class and anxious about the bad news that might greet them when they get home. Friends disappear without warning.

Ask the kids and they’ll tell you about the little ways it hurts, too — about the little joys of going to school that are now slowly disappearing. For Andres Lopez Jr., a sixth-grader who plays soccer and flag football at Westside Elementary, it’s the scruffy playing fields pockmarked with holes: “Every season, we lose versus Raisin City. They got a lot of fast people, that’s why. We got a lot of gopher holes and they don’t. Their fields are way better, because they actually have water to water their grass.”

In Alpaugh, custodians are now accustomed to working overtime to clean up the half-inch of dust that coats hallways after severe wind storms. On “dust days," kids stay inside for gym class and recess: Triple-digit temperatures, poor air quality and parched schoolyards make it too dangerous to go out, especially for the growing number of students with asthma. Occasionally a water truck comes by to spray down the farm across the street from a school entrance and, for a few lucky hours, the dust cloud disappears.

In the drought’s unrelenting grip, this is the new normal.

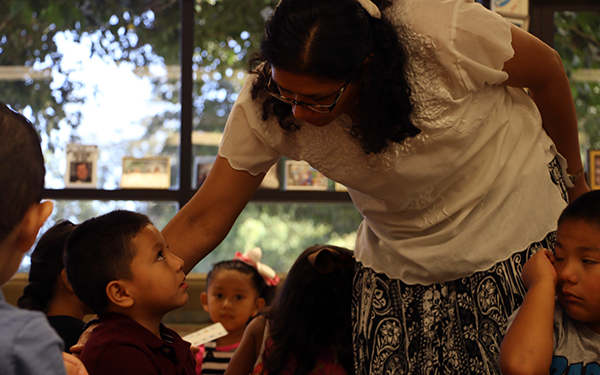

Kindergarten teacher Martha Sanderson talks with 4-year-old Danny Lopez on the first day of school at Westside Elementary, Aug. 13, 2015. (Photo by Heather Martino)

Looming amid the daily hardships and the slow, steady exodus of students, the valley’s rural schools face a greater uncertainty: Survival, not just as educational institutions but as the connective tissue of proud, multi-generational farming communities that have been the backbone of the state’s rich agricultural industry for decades.

“You lose the schools and the roots are gone,” says Javier Guzman, a former farm worker and retired state health department employee who heads the Comite Agua Para La Tierra, or Water for Land Committee, an advocacy group.

And unlike the patchwork of empty brown fields that surround a southward traveler on Interstate 5, the ripple effects of the drought on schools and students are less tangible. They’ve gone mostly unnoticed, perhaps ignored, by the policymakers who could help, residents say.

“We are all affected by agriculture and it drives us. As agriculture goes, that’s how the rest of the valley would go,” said Robert Hudson, Alpaugh schools superintendent. “I don’t think there’s anyone who’s from here who doesn’t get it. It’s just that we’re small and there’s not that many of us (residents of the Central Valley). The rest of the state doesn’t get it at all. The people in Los Angeles, in the cities, definitely don’t get it.”

The ‘maldistribution of water’

Late summer and early fall used to mean the roads running through Five Points, an unincorporated area in Fresno County where Westside Elementary is located, were slick with smashed tomatoes fallen off produce trucks.

The last two years there have been few tomatoes and even fewer trucks on these roads some 37 miles southwest of the city of Fresno.

Statewide, a UC Davis study estimates the agricultural economy will lose about $1.84 billion this year, along with 10,100 seasonal jobs, because of the drought, with the Central Valley hardest hit.

Ask about the drought in Baldo Hernandez’s circles in the San Joaquin Valley, and you’ll be told it’s a natural disaster that’s being exacerbated by what people have taken to calling the government’s “maldistribution of water” or a “reallocation of a resource.”

Andres Lopez at work irrigating grape plants on a raisin farm in rural Fresno County. (Photo by Heather Martino)

For decades, California’s vast public water infrastructure has operated on a series of contracts between the government and three main types of water customers: Residential, environmental and agricultural.

The ingredients of drought — searing temperatures, lack of rainfall, and a shrinking mountain snowpack that has historically fed the state’s reservoirs — have depleted the water supply since 2011. In response, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that manages dam releases and public water projects in California (and other areas of the West) has cut off the flow of water to growers in the south-central part of the state — gradually at first and, in the last two years, completely.

Without the quadrillions of gallons flowing south from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, farmers have aggressively tapped into local groundwater sources to irrigate their fields, which strains the aquifer and causes land shifting and shrinking.

Water customers in urban centers and farms with senior water rights maintain a supply, albeit a limited one. And fish, like the salmon and steelhead protected under the Endangered Species Act, get cold-water releases to spawning grounds to ensure they don’t die out. The government’s environmental contracts, in particular, have been a flashpoint in the wars between farmers in the politically conservative valley region and environmentalists in urban centers supported by many Democrats.

The darkest red indicates "exceptional drought," which includes most of the Central Valley. The bright red indicates "extreme drought." Other shaded areas indicate less severe drought. (Sourc: U.S. Drought Monitor)

Stakeholders on both sides have filed lawsuits. Meanwhile, Congress is gridlocked on legislation that could bring relief.

“There’s a lot of politics. If we could get the politics out of the way and make people more important than fish, then I’m an advocate. I like to fish salmon out in the ocean, but not at the expense of all of us here. I think people should come first,” said Tom Barcellos, a Pleasant View school board member who runs Barcellos Farmers in Porterville and T-Bar Dairy in Tipton.

Hernandez, Guzman and others met with U.S. Bureau of Reclamation representatives in June to ask that their needs also be considered. The response: “There’s not much we can do.”

“We are appreciative and empathetic to that view and try to work with that perspective, which we think is a legitimate perspective, but we also are constrained by state and federal law and the contracts that have been in operation for over 50 years,” Michael P. Jackson, area manager for the bureau’s South-Central California office, said in an interview.

‘Baldo:’ Superintendent, mayor, maestro, marriage counselor

A few months before the meeting with Bureau of Reclamation representatives, 10 families in a workers’ housing complex in Five Points received eviction notices. A pistachio grower who managed the site had a water shortage and was angling to tear the buildings down, according to Hernandez.

The superintendent spent the months leading up to the June 30 eviction trying to find alternative housing for the distraught residents, including one elderly woman who had lived there for 50 years.

Hernandez and his wife, Robin, a teacher at nearby Golden Plains Unified, are used to knocks at their door late in the evening from parents who have nowhere else to turn when things go wrong — with marriages, jobs, car engines or immigration forms. Their house sits next to the school and serves as de facto Town Hall, counseling center, Internet cafe and, on occasion, homeless shelter. Some people call Hernandez “maestro” or “mayor” and in many ways, that’s what he is.

Westside Elementary Superintendent Baldomero Hernandez directs students on the first day of school, Aug. 13, 2015. (Photo by Mareesa Nicosia)

On school grounds, Hernandez, 60, walks with the efficient gait of an aging cross country runner and speaks gently, with a Southern California lilt. His voice sometimes brims over with a preacher's intensity, like when he gave his staff a pep talk the day before students returned. Negativity on the job will not be tolerated, he said sternly.

“We’re a servant of the man upstairs, and he’s told us, ‘Take care of these kids here. Educate them to the best of your ability, that’s why you went to school, that’s why you came here.’ And they deserve it.”

Hernandez knows the experience of his young students well: Born in Mexico, he immigrated to California with his parents at age 5 and attended Westside Elementary. At 20, he married Robin, the 18-year-old sister of his best friend. Both came from families who worked in agriculture — and expected their children to do the same — picking grapes, picking lettuce, moving sprinkler pipes.

“The whole family had to do it just to be able to survive,” Hernandez said.

He continued working in the fields after earning his teaching certification and bilingual specialist credentials at Fresno State University. But Robin urged her young husband to quit farming and put his education to good use. He returned to Westside to teach in 1981 and became superintendent/principal in 1995.

The couple raised three children in their house next to the school and are now the full-time guardians of a grandchild. They’re also godparents to two of the six Lopez children, all current or former Westside students, who live across the street.

“I don’t want to go half way.”

Ubalda and Andres Lopez moved their family from Toluca, Mexico 10 years ago. Because Andres’ skills are versatile, he’s had steady work irrigating fields; his wife works seasonally in an onion processing facility, but has less work in recent years. Both labor from dawn till dusk, stretching their minimum wage earnings as far as they can.

Because of their stability, they consider themselves relatively more fortunate than many of their neighbors. And yet, they worry. About fields going fallow, about losing their house, about the Westside school closing, about having to return to Mexico. A lot of the time, Ubalda Lopez says, she worries about their youngest son, Danny, who just started kindergarten.

Andres Lopez drives to pick up his work assignment most days at dawn. He often spends 12 hours a day in the fields. (Photo by Heather Martino)

Yesenia, the couple’s oldest daughter, is a sophomore at California State University, East Bay, studying business. To help pay tuition, she spent the summer waking up at 3:30 a.m. to go to work at the onion plant with her mother. As the first sibling to attend a four-year university, she feels pressure to set a good example for her younger brothers.

“I want to finish until I’m done with my degree. I don’t want to go half way,” she said. “It’s going to be hard (without financial support from the family) … but it’s worth it.”

Fighting for emergency aid

Hernandez, his staff and students have written and called lawmakers and traveled to Sacramento, the state capitol, to advocate for loosening water restrictions and maintaining school aid even as students leave.

They won a small victory in March 2014 when the state added drought to the list of emergency conditions under which districts can apply for a waiver to maintain aid levels.

California’s education funding is based on average daily attendance, so superintendents like Hernandez expected their aid to slide as students moved away.

Eighteen months later, however, only one district, Firebaugh-Las Deltas Unified, has completed the application, according to a state spokeswoman.

Hernandez pushed unsuccessfully for the state to attribute his district’s gradual enrollment decline to several years of drought, he said. Firebaugh, on the other hand, saw a drastic reduction, 61 students, in just one year and was able to recoup about $500,000, Superintendent Russell Freitas said. The district lost 120 students over two years.

Pleasant View Schools Superintendent Mark Odsather and custodian Keith Stewart expect their 50 to 60-year-old well to run dry within a year or two. They've drilled a new one on district property. (Photo by Mareesa Nicosia)

Though the state announced the waiver in a press release after officials visited Fresno, the news didn’t appear to reach all interested parties in the valley.

Pleasant View Superintendent Mark Odsather, who is regularly in touch with his counterparts in the region, seemed surprised by the existence of a waiver when made aware of it by this reporter. He said his district will now submit an application.

“It didn’t seem like it was readily available,” Odsather said. “I don’t know where things kind of got lost in the mix, but you’d think that (districts in) Tulare, Kings, Kern, Fresno counties, they’d all be interested in knowing — one, that it was available and two, how to go about applying for it.”

Pleasant View has spent $160,000 over the last year to dig a new well that will replace the current one that is 50 years old and drying up fast. The district dipped into its reserve fund and used energy cost savings from new solar panels to avoid swallowing up student programming dollars.

“We can afford to put in the well, but I would have liked to spend it on other things,” Odsather said.

He also would have preferred to use the hours he spent with the drilling contractors working with staff on individualized instruction plans for each student and training teachers to use student-driven learning techniques.

Pleasant View serves some of California’s most at-risk children: 100 percent qualify for free- and reduced-priced lunch, one marker of poverty, and 70 percent are English Language Learners. The mobility rate in one recent K-8 cohort was 80 percent, Odsather said.

“We’ve got to find ways to meet kids where they are,” he said.

Historically, California has urged its many small school districts to consolidate, and the number of districts has declined by half in the last 50 years, according to a 2011 study. But while local education officials often share services and staff with the next district down the road, many resist the idea of a formal unification.

“We have not seen anything that says it saves money or it’s better for students,” said Debra Pearson, executive director of the Small School Districts’ Association, which advocates for member districts including Firebaugh, Westside, Alta Vista and Alpaugh.

Students stressed, some just disappear

In 37 years of teaching at Westside Elementary, Susan Perry can’t remember a time when her students’ anxiety was more palpable. The stress isn’t about passing a test or acing a research project. It’s about having their basic needs met.

She’s watched students cry, heard a boy boast with false bravado to mask the fear he felt as his family prepared to uproot because of job loss.

“Kids shouldn’t have to be worried about, you know, ‘How are we gonna pay the electric bill?’ Kids shouldn’t have to worry about, ‘Are we gonna have enough money for groceries?’ And yet, these kids are. They are directly impacted by it,” Perry said.

“Digging up archaeological bones and finding out what happened to people in the year 2000 BC really isn’t quite as relevant as wondering what’s gonna happen with my family next week.”

Then there was the student in her sixth-grade class who, Perry recalls, didn’t tell her — or anyone — he was moving. The next day she took attendance and another student reported to her that his friend had moved away during the night.

“They were just — gone.”

Sixth-grade teacher Susan Perry greets students in her classroom at Westside Elementary. (Photo by Anne Lagamayo)

Ninety miles east near the Sierra Nevada foothills, second-grade teacher Laurie Madrigal also witnesses the drought’s emotional toll on her students in the Alta Vista district.

“Their clothes aren’t clean so they’re embarrassed,” she said. “The kids think that because they’re on this side of town, they don’t matter. Nobody’s paying attention to them.”

The pre-K-8 district enrolls about 600 students. Dozens of them live in East Porterville, which is not connected to the municipal water supply. Instead, homes are served by individual wells that have long since run dry.

For drinking, cleaning and flushing toilets, families draw from a 500-gallon water tank in the front yard. At times, parents have kept their kids home from school rather than send them wearing dirty clothes, Madrigal said.

Alta Vista Principal Cliff Cantrell said officials are surveying families for the second year in a row to keep track of how many are without water. As the numbers rise — the 39 last year will surely double, he predicts — employees work with civic groups and the local community college to organize water drives to try to keep up.

“There are a lot of factors involved that may not show up in numbers, but you wonder what (the students) are thinking,” Cantrell said. “That’s something that you can’t always measure but … it’s gotta be there.”

Physiological effects of prolonged stress on children can manifest in weight gain, behavioral issues, high blood pressure and, later, trouble managing emotions as adults, said Cathy Yun, an assistant professor and program coordinator for the early childhood education program at Fresno State University.

“When you have kids who are stressed out, they’re going to act out in school, they’re going to have trouble getting along with their peers, they’re going to have trouble self-regulating. It has implications on learning for all the kids in their class,” she said. “It’s this really kind of dangerous potential for this domino effect.”

Eighth-grader Irene Hernandez (no relation to Baldomero or Robin Hernandez) is a new arrival in Pleasant View’s migrant program. Her parents have moved looking for work four times since she was in third grade, landing her and five siblings in a different district each time.

“You have friends at the school and then you move to another one and you don’t know who they are,” she says. “You might get behind in your work.”

A water tank sits in the front yard of a home in Porterville, Calif., supplying drinking and washing water to residents. Wells started running dry over a year ago. (Photo by Heather Martino)

Dust days

The fine silt that whips up from the dry Tulare Lake Basin has choked the Alpaugh school district increasingly in the last year and a half, seeping under doors and through window cracks. Smoke drifting from wildfires makes the air quality even worse.

During the hottest, grittiest weather, Superintendent Robert Hudson and his staff call “dust days,” where kids stay inside for gym and recess. Many of the students have asthma, and Hudson says his office is full of “coughing and honking” because of the conditions. It’s just another fact of life in the drought.

“We just have learned to work around it, and guess what? We’re going to keep educating kids no matter what,” he said.

In Alpaugh, a pre-K-12 district in Tulare County, about 90 percent of the 360 students are children from agricultural families; 97 percent are considered high poverty. Alpaugh hasn’t seen the enrollment drops that Pleasant View and Westside have — it actually had an abnormal 17 percent uptick in the high school last year — and Hudson believes one reason is because families are too poor to move.

“Traditionally, yes, (based on) the amount of rainfall, you could definitely predict what your ADA (Average Daily Attendance) was going to be … but last year and this year that wasn’t so. I don’t think people have anywhere to go,” he said. “You go to where you can afford to stay.”

Hudson, whose father developed herbicides and whose mother was an educator, is another jack-of-all-trades superintendent who has formed close bonds with his students in 11 years on the job. Families speak openly with him about their struggles, he said.

“I’m the cafeteria director, I’m the preschool director, I’m the superintendent,” he said. “I always tell the kids you can write your own destiny but you have to be willing to put in the hard work. It’s hard to focus on what you need to do when you’re hungry, when parents aren’t earning enough money, when they’re worrying about keeping the electricity on. When the kids come to school and I see they’re hitting the breakfast like there’s no tomorrow, I know.”

One of two elementary school sites in the Pleasant View district in Porterville, Calif. (Photo by Mareesa Nicosia)

There is also resilience in the close-knit community schools.

Alpaugh is replacing buildings whose foundations are crumbling due to high sodium levels in the soil, and Hudson hopes the new facilities will help retain students.

In Westside, teachers, who make on average

$49,000 a year, will get a pay raise this year. Pleasant View students are using laptops and tablets, and Porterville is collaborating with local businesses to set up high school students with internships.

It’s these tiny gains that school officials say they cling to as they wait — for rain, for Congress, for an act of God.

My community, my people

Back in Five Points the day before school started, Hernandez stood at the front of the classroom, urging his staff of 27 to be active this year in advocating on behalf of the school and community.

“This is my community, my people, so to speak,” he said, his pitch rising. “This is my home … and for a lot of people, this is our home. … And I’m going to do everything I can to make sure my home is OK, and you need to help.”

He called out the names of a couple veteran staffers who’ve been his neighbors and colleagues for decades. Three brand new teachers, recent transplants, listened gravely.

The yard in front of Westside Elementary School in Five Points, Calif., is bare and dry. (Photo by Heather Martino)

Susan Perry, a 37-year veteran, was sitting off to the side. She sighed.

Sitting in her quiet classroom later, Perry says that she can see the weight of this drought in those who live in her community. She recognizes the slump in the shoulders of the parents and the students that simply wasn’t there before.

“It’s like, what do we do next? What’s going to happen next? If we don’t advocate, this school will dry up and blow away and nobody wants this community lost. There’s just too much of value out here. Whether people in cities see it, that’s not our issue. But there’s value here, there are human lives here. There’s a way of life out here.”

;)