The Education Department’s Title IX Proposal Is ‘Out of Step’ With Realities of Sexual Harassment in K-12 Schools, Groups Warn as Comment Period Closes

The Education Department’s proposed rules governing how schools handle allegations of sexual assault on campus don’t account for the specific needs of K-12 schools, advocacy groups say.

More than 100,000 comments flooded the department by the time the comment period closed Wednesday night. K-12 advocates said that beyond their overarching concern that the proposal would set an unduly high standard before schools must address sexual harassment, the new rules about which school personnel must be notified before an investigation begins could conflict with existing law requiring employees to report child abuse.

The proposal, unveiled in November, would generally strengthen the rights of those accused of sexual assault and harassment, while limiting the situations in which schools must intervene. It’s a clear move away from rules put forward during the Obama administration, and it immediately drew rebuke from women’s groups and civil rights advocates.

Though the regulations are more often thought of in the context of higher education, the federal law under which they’re written — Title IX, which prohibits discrimination in education based on sex — also applies to K-12.

And that, advocates say, is part of the problem.

“It’s pretty clear to us that this set of regs was targeted much more to higher ed without a lot of consideration to K-12,” Bob Farrace, a spokesman for the National Association of Secondary School Principals, told The 74.

Americans filed a whopping 102,966 comments by the time the comment period closed Wednesday. Only 8,938 are posted online; the department filters out comments it says are duplicative or those that contain private information or inappropriate language. Under federal law, department officials must read all the comments and respond to those that warrant it; at least one higher ed advocate predicted a final rule won’t be proposed until Thanksgiving.

The Education Department in its proposed guidelines did specifically seek comment on “whether there are parts of the proposed rule that will be unworkable at the elementary and secondary school level” and if other proposals, like those concerning cross-examination of complainants, should be altered based on students’ age.

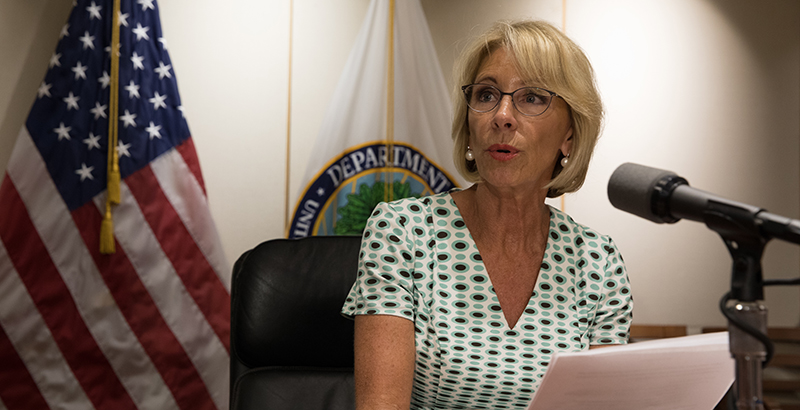

Department press officials did not respond to a request for comment on whether the department had appropriately accounted for the unique needs of K-12 schools when writing the proposed regulations.

One of the main changes in the proposed rule would require schools to intervene only when harassment becomes “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access” to education.

That’s too narrow a definition and will discourage reporting, education groups argued.

“Students who experience what are perceived to be ‘minor’ forms of harassment may be disinclined to report the harassment given the specificity of the definition as proposed,” the National Parent Teacher Association said in its comments.

The department in its November proposal said the new definition better aligns with Supreme Court precedents on the issue.

K-12 concerns

One of the major proposed changes to the Title IX regs involves who in a school must be told about an allegation of sexual misconduct to trigger an investigation.

For K-12, only notification to a school district’s Title IX coordinator or a teacher would constitute sufficient notification of student-on-student harassment. Importantly, education advocates say, that doesn’t include other school personnel like special education aides, coaches, or other adults with whom a student may have a closer relationship. Long-standing federal guidance has required schools to intervene when any employee knows about misconduct.

“Such a rule is particularly unworkable for students who are non-verbal, students with physical or intellectual disabilities, and English Language Learners, who often have closer relationships with their teacher aides, members of their [special education] team, school psychologists, and other school employees who are not their teachers or the Title IX coordinator,” a coalition of civil rights groups, including both major teachers unions, said in their comments.

For harassment of students by school employees, only notification to a district’s Title IX coordinator would constitute sufficient notification under the proposed rule to trigger an investigation. The department says that means “every student has a clearly designated option for reporting sexual harassment to trigger their school’s response obligations.”

These standards, however, appear to conflict with many state laws that require nearly all school employees to report any suspicions of child abuse, advocates say.

So school personnel could be required under state law to report an incident to child protective services but not otherwise undertake any kind of investigation or provide remedies at the school level.

Many district leaders would still do the right thing and investigate if they receive a report, even if not required under the new rules, but setting different standards sends the wrong signal, said Sasha Pudelski, advocacy director at AASA, the group that represents superintendents.

“It’s messy. It’s unnecessarily messy. I don’t think it achieves the goal that we hope these regs are intended to achieve, which is to make sure every child has a safe learning environment,” she said.

Not everyone objects to the new rules.

Republicans on the House Education and Labor Committee, for instance, praised the department for using the formal rulemaking procedure, rather than the informal “Dear Colleague” letter the Obama administration used. They also lauded the proposal for keeping with Supreme Court precedent and defining the conditions that must be met to trigger a school response.

On K-12 specifically, the department is “taking a step in the right direction” in considering differences, R. Shep Melnick, a professor at Boston College, told The 74. “They’ve just begun to examine that question.”

The regulations, for instance, do not require live hearings at the K-12 level to adjudicate the issues, as would be required in higher ed, he said.

In general, the final regulations should clarify that they set a minimum standard for dealing with allegations, which may be surpassed by state law or local regulations, he said.

“Schools at the K-12 level have much more responsibility of making sure that childhood behavior does not become too extreme. Clearly what schools are going to have to do is establish their own lower level requirements of what constitutes acceptable behavior, but of course they’ve always done that,” Melnick said.

There are other, more specific ways the proposal doesn’t consider K-12, Farrace, of the principals’ group, said.

The rules, for example, require different school officials to investigate and then adjudicate allegations of assault. That could be difficult in very small school districts where principals already do more than one job, such as serving as superintendent.

“These regulations are pretty well out of step with what is happening with K-12 schools and what the needs of K-12 schools are,” Farrace said. “Sexual misconduct is a far more complex issue at the K-12 level than the regs would suggest.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)