The ‘Diplomas Now’ Way: Better Identify At-Risk Kids, Do Whatever It Takes to Get Them to Graduation Day

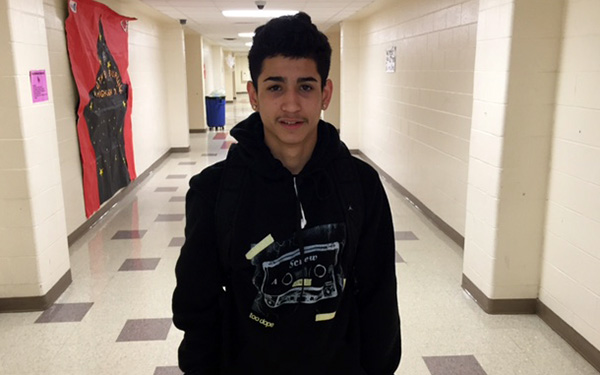

(San Antonio, Texas) — First period was just about to start, and Angel Mendoza was already asleep at his desk.

He’s often tired at school after working late-night shifts in the kitchen at Alamo Pizza, but he needs the money and the busy schedule keeps him out of trouble.

“Honestly, sometimes I don’t even do my homework,” said the 18-year-old senior at Luther Burbank High School. “I just come to school and do my homework in class or something, or if I’m off I’ll do my homework.”

Plopped at the intersection of two freeways on the city’s south side, Burbank is surrounded by small, single-family homes with faded paint and yards with brown grass and overgrown trees. Nobody here lives too far away from their aunts or uncles, brothers or cousins. Breakfast tacos from a hole-in-the-wall cafe down the street are a morning staple.

When there was talk about shuttering the school a few years back because of declining enrollment, everybody rallied together to save the place. But the area does have a reputation for being unsafe. In November, Burbank High School — a hodgepodge of new and old buildings surrounding a quaint courtyard — went into lockdown after a bullet zipped through a classroom window.

Mendoza wishes he didn’t have to go to school there at all — he’d much rather just work and make money. But he also doesn’t want to make pizzas for the rest of his life. He loves the outdoors and dreams of someday becoming a zoologist in Jamaica.

To get there, he’ll first have to pass all of his classes and graduate from high school, then college. Along the way, he’ll have to control his anger.

Mendoza said he can’t pinpoint the cause of his anxiety but his home life certainly can’t help. Mendoza and his younger brother and sister live with their aunt and her boyfriend. His mother is addicted to drugs and his father died when he was six.

“He had a heart attack,” Mendoza said. “I think he would drink too much. He was an alcoholic.”

Like a lot of students at Burbank, where 98 percent of the population is Hispanic and more than 90 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, these out-of-school circumstances make it difficult for Mendoza to focus on academics.

“A lot of my classmates have dropped out, or, we have a smaller senior class this year,” Mendoza said. “Like, all of the kids we went to school with, like they either dropped out or they don’t come to school anymore.”

But with the right supports in place, he’s on track to graduate on time. For the last few years, a social worker targeting Burbank’s most at-risk students was ever-present and helpful.

“She was just there to talk all the time, like she always had a smile on her face,” Mendoza said. “She would talk to me about my problems and she would help me overcome them.”

Supports such as that are part of a whole-school approach called Diplomas Now, an initiative that brings together three national organizations to do whatever it takes — inside the classroom and out — to ensure the most at-risk students at Burbank, and other distressed high schools across the country, reach the finish line.

Previously an underperforming school, Burbank has made huge academic gains in the last few years and is now among the most successful comprehensive high schools in the San Antonio Independent School District. With Diplomas Now currently in its fourth year at Burbank, the group strives to prove it’s made a difference — with hopes the program will still be around to help kids next year. Mendoza’s Class of 2016 is the first one at Burbank that Diplomas Now has followed since freshman year and much is riding on its outcome.

“The reality is, one day they are going to go away,” said Blanca Rojas, a first-year assistant principal at Burbank. “They come in and then they are going to leave, so we just have to be realistic about ‘OK, if they’re not there, what do we do? How can we continue to do what we currently do with less manpower?’”

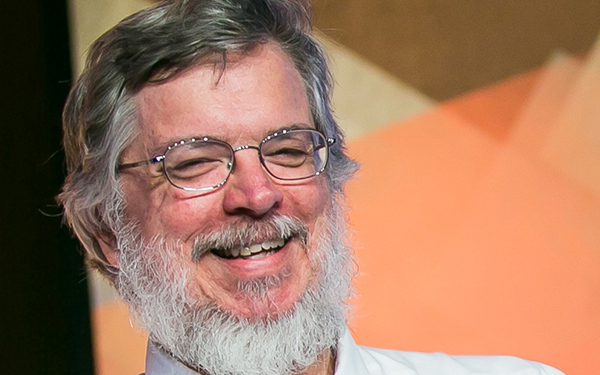

It was the 1990s and Robert Balfanz thought the grandeur of the graduation celebrations at some urban high schools he visited as a researcher seemed strange.

All the clapping and cheering was for about 100 kids who walked across the stages in caps and gowns — a milestone their families were rightly proud of but one that struck Balfanz as oddly forgetful of all the other young people once part of that class when it began as freshman. During visits to these schools, Balfanz remembers seeing more students in the hallways than the classrooms.

“It was sort of this odd thing that you have these wild celebrations for what was clearly a small fraction of the kids,” said Balfanz, a research professor at the Center for the Social Organization of Schools at the Johns Hopkins University School of Education in Baltimore. “So then we just started asking ourselves, ‘Well, did we just randomly end up in a couple of the really crazy, worst schools in America, or is this more of a thing?’”

At the time, states didn’t use the same formula to determine schools’ graduation rates. But by the 2000s, Balfanz started tracking the schools’ “promoting power” — a statistic that showed how the class sizes at these schools shrank between freshman and senior years.

In a “suburban experience,” schools would lose a small fraction of students for various reasons.

In a subset of about 2,000 high-poverty schools, the winnowing was much starker: class sizes shrank by about 60 percent between freshmen and senior year. That meant these high schools produced half of the nation’s dropouts.

“That was one of the big ‘ah ha’ moments, right? That’s because like 12 percent of schools were driving half of the problem,” he said.

Inside the classrooms, the conditions that led to such low retention, he thought, were very mechanical in nature. It was like a factory. A “Dropout Factory.”

During the first semester of freshman year, these students would fail to turn in assignments, they’d get zeros, and they’d get failures on their first-semester report card. Soon enough, they’d be asked to repeat a grade — and they’d put in even less effort the next time around. Typically, the students would then go to an alternative school for a short time before giving up on high school altogether.

“It just sort of insults my notion of what America should be,” Balfanz said. “In the 21st century, you can’t get to the land of opportunity if you don’t have a high school diploma, and we still haven’t quite created a level playing field for everyone to get one because we still have our neediest kids hyper-concentrated in a subset of schools.”

In order to make a dent, Balfanz turned to a group he heads, Talent Development Secondary, which uses research to figure out which supports students, teachers, and administrators need most. In this case, it focused on changing the way the schools were structured. The program made sure freshmen teachers were the most experienced and most dedicated. They grouped students into sections that were taught by common teachers across all core subjects, allowing time for teachers to compare how the students were performing and behaving. Schools developed block schedules so students had only four periods each day.

“We did all that, it had a good effect, it raised attendance, it raised promotions, it made behavior better,” Balfanz said. “It took schools from like lousy to like sort of decent.”

Still, overwhelming student need persisted.

Through his research, Balfanz said he can identify half of the students by sixth grade who will eventually drop out of school. They’re frequently skipping class, getting into trouble when they do show up, and they’re often failing either math or English.

Trouble was, even though they were able to identify the kids early, schools were stretched beyond their capacity to respond.

So during the 2008-09 school year, Balfanz co-founded Diplomas Now as a pilot project at a 700-student middle school in Philadelphia, pairing three organizations with school officials to focus on a singular mission. By tracking those early warning signs — poor attendance, bad behavior, failing grades in math or English — Balfanz’s research shows that 75 percent of America’s high school dropouts can be identified between sixth and ninth grade — the most critical years of support for students.

Meanwhile, students who have a smooth transition from middle school to high school, and then from ninth to 10th grades, are about four times more likely to graduate from high school than students who are considered “off track” at the end of ninth grade.

The first of the Diplomas Now partners is City Year, an AmeriCorps program that hires young adults for a year to serve as tutors, mentors, and role models for students. Then, for the schools’ most at-risk students, is the nation’s largest dropout prevention organization, Communities in Schools, which connects students and their families to community resources, from food to one-on-one counseling. The last piece that brings it all together is the data identifying which students are veering off track that comes from Johns Hopkins University-based Talent Development Secondary.

Now, the organization serves about 26,000 students in 13 cities — from New York to Seattle to Miami — expanding in part through a $30 million federal Investing in Innovation Fund Grant received in 2010 and $16 million from the PepsiCo Foundation.

In 2012, Burbank High School was selected to participate. But the federal grant money that allowed the program to expand to Burbank, and to other schools across the country, is now gone.

The federal grant to Diplomas Now is one in a handful of federal initiatives to boost high school graduation rates nationwide. Since 2010, for example, schools across the country have used a common metric to report graduation rates in order to promote greater accountability and to develop strategies to reduce dropout rates.

In December, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics released a fresh batch of numbers that placed the nation’s high school graduation rate at 82 percent for the 2013-14 school year — the highest ever.

Still, a January report by GradNation noted that America’s schools fell short for the first time last year in a federal goal to bring the on-time graduation rate up to 90 percent by 2020.

Also, the report, which was written in part by the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins, noted a “severe” gap in graduation rates for minority students, students from low-income families, students with disabilities, and English language learners. About 72 percent of black students and 76 percent of Hispanic students earned diplomas compared to 87 percent of white students.

The report did highlight some good news: the number of “dropout factories” declined to 1,000 schools, compared to the roughly 2,000 in 2002 when Balfanz started to dig into the problem.

In the back row of Arturo Rivera’s freshman algebra class, a young woman in a bright red shirt whispered to a student needing a little extra help with the lesson. Rivera, who has been a teacher at Burbank for eight years, is used to the whispering by now because the helpers are in his classroom every day.

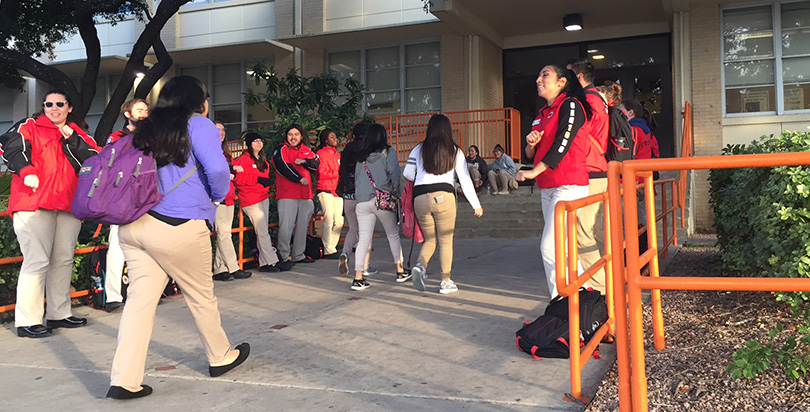

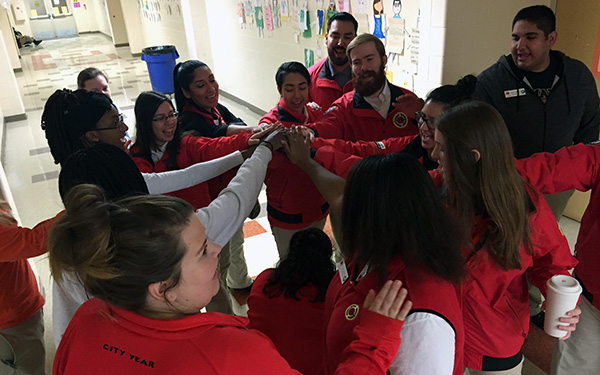

Seventeen young adults in the same identifiable red shirts — City Year corps members who committed to 10 months of service at Burbank after a five-week training — are everywhere at the school, even before classes start.

“Being able to fully understand their neighborhood, their upbringing,” is the hardest part about becoming a corps member, said Frank Lopez, City Year’s impact manager for Burbank. Lopez served two years as a corps member at another San Antonio school, Sam Houston High School, before becoming a teacher for a year. He rejoined City Year in a leadership role at Burbank this year.

Sometimes, the corps members can be spotted in the parking lot handing Krispy Kreme donuts into car windows as parents drop off their children for the day. Sometimes, they’re at the entrance of the school, clapping and chanting as students trickle up the stairs into the building. Sometimes, the students stop to clap and dance, too.

“P-O-W-E-R. We got the power cuz this – is – Bur – bank.”

Past the statue of Luther the Bulldog inside the main building’s front entrance, corps members can be found talking to students in the halls, tutoring in the library, and calling the parents of kids who didn’t show up.

Paid a small stipend for the work, the corps members are between 17 and 24 years old — not much older than the kids they’re trained to mentor.

“It’s not like they look at us like we are these wise adults, you know,” said Ignacio Treviño, a corps member who also grew up in San Antonio. “They just look at us as somebody to, I guess, role model themselves after.”

Before accepting the gig, Treviño had dropped out of college and was working two dead-end jobs for $8 an hour. He saw City Year as an opportunity to get back on track. The reasons corps members accept the job varies: A few are interested in becoming teachers themselves, while others aren’t quite sure yet what they want to do with their lives. For Marissa Esquivel, working with kids in San Antonio was the driving force. She was raised just down the road from Burbank.

“I grew up where a lot of people needed help and I knew that they were good people, and they were really smart, they just didn’t get the help they needed,” she said. “I didn’t always feel like in my high school I got the help I needed.”

When the first corps member was assigned to Rivera’s classroom, he was reluctant to get that help.

“I didn’t think it was going to work out, like working with one person all the time, all day,” he said. “Why are you giving somebody to help me? I’ve always managed alone. And now, I’m going to say I need them now.”

With 150 assignments to grade a day, being a teacher is tough — especially when he says he could make more than the $52,000 a year he earns being in the classroom fixing cars or cutting hair.

Sometimes, the 29-year-old teacher thinks he doesn’t want to do it anymore, but he keeps coming back for the kids. He can relate well to them because he also grew up in the neighborhood and went to school at Burbank, graduating in 2004. Like many of his students, he said, his parents were Mexican immigrants who never received their high school diploma.

Rivera is able to understand his students even better through the Early Warning Indicators meetings, a collaboration between teachers and Diplomas Now members,

“I like going to them because you talk about the kids and you get to know the kids, like how they act in other classes,” he said. “If you build relationships with the kids, they’ll do anything for you.”

Gathered around a table in the middle of the Diplomas Now headquarters at Burbank — a converted classroom — Sheryl Lew passes out a list of nine students to a small group of teachers and her co-workers. As the school transformation facilitator, Lew runs the show at Burbank. She’s the only Diplomas Now member who gets a paycheck from Johns Hopkins.

Collecting data on students’ attendance, behavior, and course performance, Lew’s list comprised students who were having the most trouble. Sending the data to Johns Hopkins, she saw how Burbank was performing compared to other schools with Diplomas Now support. This time, 81 percent of the freshmen didn’t have any of the early warning indicators.

“In attendance, we came up to 91 percent, but Tulsa beat us this time,” Lew told the small group. “It’s interesting that the behavior and the ELA and the math, it stayed the same (at Burbank), but this (data) is looking good.”

Running down the list of students, the Diplomas Now members discussed each name one-by-one to develop an intervention strategy. Then, members of the group were assigned to be a “champion” to work individually with the students.

A day after that meeting, Lew sat with the student she agreed to work with, a freshman who propped his chin up with his palm and stared down at the table’s fake wood veneer. The student, whose parents did not give permission for him to be identified, hadn’t turned in a handful of assignments and his grades were starting to slump. She offered to give him a new journal, since he lost his at a friend’s house. She gave him a few folders because organization was an apparent issue. But when he missed school, that was on him.

“When you’re absent, you need to go to the teacher and see what assignments you missed, and make it up. It’s your responsibility to do that,” Lew said. “I want you to be a sophomore next year. I want you to have six credits to be a sophomore.”

Even after making it through freshman year, Burbank’s most at-risk students need continued support in order to reach that graduation stage. That’s where Alli Dean comes in. As the site coordinator for Communities in Schools, she seeks out the students with whom she wants to work.

Along with counseling, Communities in Schools offers a variety of services, including programs that allow students to shadow local businesspeople, trips to visit local colleges, and group activities that help students build self-esteem. Mendoza, the senior who dreams of being a zoologist, is a member of XY-Zone, a leadership development and peer support program offered by Communities in Schools.

Rojas, the vice principal, hasn’t been an administrator at Burbank for long. Just last school year, she had Lew’s position. Because student behavior was improving, and because attendance and course performance were getting better, she said she could tell Diplomas Now was helping.

For example, 60 percent of Burbank students passed Algebra 1 in 2013. A year later, that number jumped up to 75 percent.

But with the federal innovation grant coming to an end, she feared the program at Burbank was over.

“I was hoping it would be at least one more year because this is the year they graduate, the first graduating class,” Rojas said. “Then at the last minute, they did find funding for a majority of the program.”

Balfanz, the Johns Hopkins researcher, said Burbank’s poor promoting power is the main reason the school remains eligible. This year’s senior class at Burbank, which has about 1,400 students, is about 60 percent the size of its freshmen class — qualifying it as a “dropout factory.”

In the last few years, however, the reported graduation rate at Burbank has jumped up: it was 84 percent in 2010 and 91 percent in 2014 — well above the state’s average of 88.3 percent. However, Balfanz called it a “Texas phenomenon” to have a considerably higher graduation rate than promoting power rates, meaning the vast majority of the kids who make it to senior year do indeed graduate but a large number of them have already been lost before they reach 12th grade. This includes struggling students who transferred to other schools or returned to Mexico with their families for economic reasons. Balfanz said the state could also have a different interpretation of the formula used to determine graduation rates, one of the most argued-about statistics in education.

Regardless, Balfanz said he doesn’t expect the data to show large signs of growth until the end of this school year. This year’s seniors, including Mendoza, will be the first graduating class to experience Diplomas Now during their full high school careers.

Despite worries from Diplomas Now members that the program could evaporate at the end of this school year, Balfanz said buy-in from school officials should allow the supports to continue even if the official program does not.

City Year and Communities in Schools raise their money independently and operate on annual contracts with the school district. Even if Diplomas Now isn’t there next year to bring all the organizations together under one data-driven umbrella, Maribel Rodriguez, Burbank’s principal, said school leaders will try to continue the program on their own.

That’s good news for Rivera, the algebra teacher who went from being skeptical about Diplomas Now to depending on it.

“It really has made a difference, and I think if it’s ever gone, it’s going to be missed,” he said. “The ones that are going to take the hit are going to be the kids.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)