The Confident Man: Kriner Cash Says He Can Fix Buffalo’s Broken Schools. Should We Believe Him?

Updated April 24

Buffalo hasn’t had a new teachers contract in 12 years. Its schools are segregated. Its board is fractured. Can a self-assured new leader with unprecedented authority actually turn things around?

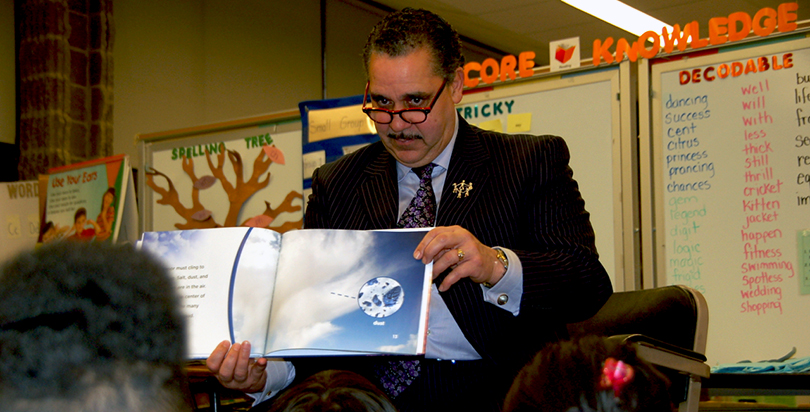

(Buffalo, New York) — As the frustrated speakers lined up, Kriner Cash sat quietly in his chair, took a sip of water, and glanced down at the pin on his lapel — a small silver emblem of five children linking hands.

The school board meeting was about to get personal.

“Dr. Cash, you are the receiver in Buffalo,” a man said, his voice filling the school auditorium. “Get us the data and the research on receivership.”

He was referring to a new law that made the dapper 61-year-old a “superintendent receiver” with unprecedented powers to fix five “persistently failing” schools in Buffalo, among 20 such schools across the state of New York.

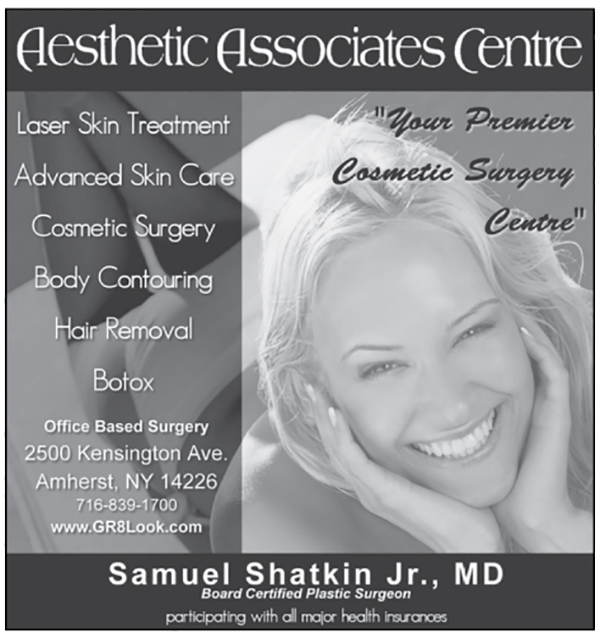

The law allowed Cash to bypass the teachers contract — which expired 12 years ago and is famous for benefits like free cosmetic surgery — to extend the school day, require teacher training on weekends, and remove seniority from hiring decisions.

“Do we have a concrete example of where this works?”

“There is no evidence to say receivership will help anything.”

One woman’s plea seemed to underlie the distrust: “Would you people please, please fight for our schools and our kids?”

While some speakers were furious that yet another set of reforms was being imposed on their schools, or about contract proposals the local teachers union president called an insult to educators, Cash’s responses were poised, direct, un-defensive.

Tasked with fixing a district where more than one-third of schools were considered failing and just 12 percent of students read at grade level, he kept his cool.

The board of education’s unanimous vote to hire Cash last August seemed to signal better times. For a moment, consensus prevailed among a group so divided along racial and ideological lines that they disagree about whether one attorney alone can fairly mediate their disputes.

The city was less physically distressed than Cash had envisioned, as well. He expected block after block of abandoned buildings, relics of the rust belt city’s decline when its economy went bust decades ago.

But Cash saw Buffalo on the rebound, with tens of thousands of new jobs expected to appear over the next 10 years at a massive solar panel plant and other new high-tech manufacturing facilities — products of a ballyhooed $1 billion state revitalization project.

One expectation turned out to be very much as Cash imagined: the Buffalo teachers union and its supporters were not pleased with his aggressive agenda or the law that elevated his authority.

Shortly before the heated school board meeting, in fact, more than 100 teachers marched in an icy wind outside Buffalo’s towering, art-deco city hall in protest.

“RECEIVERSHIP NO!,” one sign said. “WE DECIDE!”

Cash tried to allay fears that an outsider couldn’t be successful or that he had parachuted in with a prefabricated, one-size-fits-all solution.

“I’m trying to build it from the inside out,” he told The 74. “I want the participants — the teachers, the students, the families — to say ‘this is what we need to be successful here.’ And then I use the enhanced authority to say ‘you can do it. Do it.’”

Cash would need to navigate deep-rooted skepticism as well as the high expectations of business leaders and elected officials locally and in Albany.

He had to manage the noise generated by school board conflicts and the long fight for a teachers contract to have any hope of turning around a “persistently failing” school like West Hertel Academy — where only five percent of students in third through eighth grades were proficient at reading — or to begin healing the shattering effects of segregation.

He had to find his place, too, in the shifting education policy conversation in New York. The governor and a new, moderate commissioner, MaryEllen Elia, had just begun finding common ground when the state board of regents elected Betty Rosa to be chair. Rosa opposed Cuomo’s measures and contradicted Elia on testing opt-out just minutes after taking office.

Fortunately, Cash isn’t new to education politics. He was seen as an effective, yet controversial, change-maker in other cities, with a calm demeanor that belied his aggressive vision. And while a union lawsuit contesting receivership could shut him down — and the results of a rancorous school board election could constrain his ability to make change — he doesn’t plan to stop unless a judge says he must.

“We will improve this district,” Cash told the crowd at the school board meeting, speaking in a slow, southern drawl that seems out of place in a city so far north the Canadian flag is often flown beside the stars and stripes.

“Together.”

James Sampson wasn’t sure what to do. Buffalo’s superintendent position had been vacant for a year, and the school board president was running short on ideas.

Then he talked to Elia, the new state education commissioner, who surfaced Cash’s name. In their previous positions, Elia and Cash had participated in a high-profile grant program to improve evaluation of teacher effectiveness. Elia pointed to Cash’s work as the superintendent in Memphis, a challenging district similar in many respects to Buffalo, as the reason she recommended him.

Sampson said he was interested in hiring someone with national experience in education reform, “but then also creating education opportunities for kids, particularly kids of color, who seem to be left out of the equation.” He also saw Cash — exuding command in splashy Italian suits — as a leader who could calm tensions between the divided school board.

“This is a very racially divided city and we’ve got a lot of wounds that need to be healed,” Sampson said. “I was very interested in having an African American come in and help not only with education but the racial divide in the city.”

Another board member, Carl Paladino, was out of town when the school board voted voted for the new superintendent. That didn’t stop the brash real estate tycoon and former gubernatorial candidate from weighing in.

Shortly after the vote, Paladino shot off an email to a supporter that advised Cash not to mess with him or “be fitted for his career ending casket.” He described Cash as a “slick, fast talking medicine salesman” who was brought to Buffalo by “a rookie Commissioner of Education.”

Paladino, who unsuccessfully challenged Gov. Cuomo in 2010 and says he plans to run again in 2018, acknowledged that he would have voted to hire Cash had he been in town — although he said he would have preferred a local candidate with institutional knowledge about the challenges in Buffalo.

Much of Cash's career has focused on the problems that make Buffalo an inequitable home for many residents, Cash said. A native of Cincinnati, Cash wrote his thesis as a Princeton undergraduate about growing up black in America.

“Going through that process of learning deeply about my own history and place,” Cash said from his office overlooking Lake Erie, a framed picture of Harriet Tubman greeting visitors as they enter. “I said, ‘I’ve got to help others, especially young people, to learn — sooner rather than later — who they were and why that’s so important from a historical context.”

He still keeps the thesis nearby, along with a photo of the Princeton basketball team, a reminder that he used to pair an afro with his thin mustache.

Cash’s subtle drawl comes from southern Ohio; his competitiveness took shape on the basketball court — where he met his best friend, Wendell Burbridge, whom Cash later hired as an athletic department coordinator in Memphis.

“He’s one of those guys that never settled for runner up or being in second place,” Burbridge said. “He always had that demeanor about him that he was going to succeed no matter what.”

After a stint in higher education, Cash accepted his first superintendent position with Martha’s Vineyard Public Schools in Massachusetts, where he oversaw the expanding district for nine years. After a four-year stop in Florida as the chief of accountability and system-wide performance at Miami-Dade County Public Schools, he moved to Tennessee to lead Memphis City Schools, an urban school system whose challenges were similar to what he later found in Buffalo: overwhelming poverty, poor student performance, and persistent segregation.

At each stop he shook up district and labor bureaucracies, but not in a predictably ideological way. In Memphis, he honed in on teacher evaluation and school closure, (unsuccessfully trying to fire 150 low-performers in Memphis), but his agenda in Buffalo includes boosting early education and community schools.

Policy aside, he has also been a magnet for controversy. In Miami, he was fined by the state after telling a Muslim colleague his beard made him look like a terrorist. In Memphis, Cash’s personal driver, who also was part of the superintendent’s security team, was removed following reports he sent sexually explicit text messages. That same year, Cash put a deputy superintendent on paid leave for making inappropriate comments about the size of a secretary’s breasts during a party at Cash’s house.

These setbacks didn’t prevent him from becoming one of the nation’s leaders in assessing teacher performance, thanks to a $90 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Of the districts funded by Gates to build better evaluation systems, only Florida’s Hillsborough County, overseen then by Elia, was awarded more — $100 million. With Memphis’s share, Cash developed an approach combining observations, student achievement, student surveys, and teacher knowledge.

In 2013, the Memphis City Schools completed a merger with the Shelby County district to save money and improve the quality of the city schools, and Cash was out of a job.

“The school system was going to be a new school system that would be run primarily by the county and so I saw the work as different than what I signed on for,” Cash said. “At the end of the day I just decided to resign and pursue other professional goals.”

He spent two years looking and interviewing before he landed in Buffalo. He also mourned the loss of his wife, who died suddenly from cancer.

Every day, as he works to turn around Buffalo’s schools, he said he feels his wife’s presence. Once, when they were living in Memphis, she gave him the silver lapel pin of five children. It wasn’t for a particular occasion, just a little gift.

“She pinned it right here and she said, ‘when you get in your day, and you’re feeling frustrated and the adults are making things more complicated than they should, let this be an anchor for you, let it recenter you on what’s most important,” Cash said, holding back tears. “The children. That’s why you do what you do.”

West Hertel Academy looks quite a bit different today than it did when Monica Capozzi started teaching there in 2004. That was before elementary grades were added to the junior high. She saw four principals churn through before Cecelie Owens, the school’s current leader, arrived in 2014.

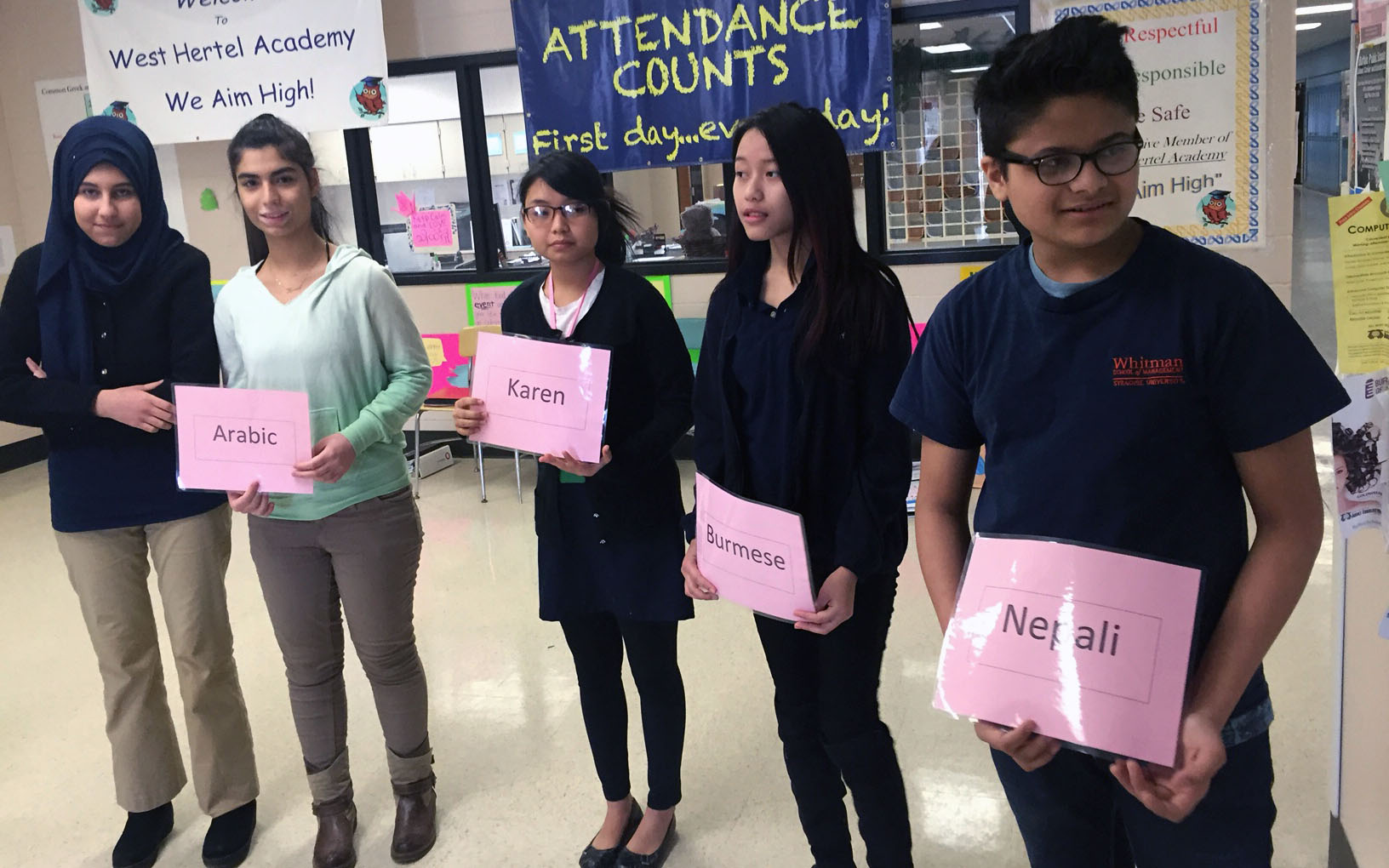

Capozzi watched as the provenance of her students changed, too. Today, about 35 percent are English language learners. Systemwide, 16 percent began as English language learners — a 60 percent increase from six years ago.

For her part, Owens expects improvement. Soon, she believes, it won’t be the same school that has failed state requirements for the last decade.

“The transformation of our district is, I think, critical,” she said. “I think it’s necessary. We need a major overhaul in this district. We’re doing some great things in Buffalo and people really need to know.”

That’s where New York’s new receivership law comes in, at least for West Hertel.

The law emerged during state budget negotiations last year to promote rapid improvements at long-struggling schools. In July 2015, the state announced superintendents would be given one year to improve student performance at schools that had failed state accountability tests for the last decade. One-quarter of the schools in the state, five of 20, were in Buffalo (another school elsewhere would be added).

Additionally, a larger group of “failing schools” — those deemed to have failed for the past three years, rather than 10 — were given two years to make improvements. Twenty of 124 were in Buffalo.

State officials later announced that three of the five Buffalo schools deemed “persistently failing” would be removed from the list because, prior to receivership, they improved on accountability measures like test scores (schools in other districts have come off the list, also).

The stakes are still high for the remaining two schools, West Hertel and Marva J. Daniel Futures Preparatory School, which risk being taken over by an independent receiver, such as a charter operator, if they don’t show improvement this year.

In the fall, Cash proposed 10 changes to work rules he thought would help the struggling schools, such as allowing the district to deny teacher requests for transfers out of them.

The union, Buffalo Teachers Federation, was not amenable; when talks went nowhere, Cash sought Elia for help. She imposed a “receivership collective bargaining agreement” that allowed him to move forward without union approval.

Owens saw the enhanced authority as a lifeline.

The West Hertel Academy principal remembers sensing a toxic environment when she first walked into West Hertel last year. Teachers didn’t trust the leadership, she said, and they were unwilling to take risks. Ultimately, a good chunk of her teaching staff left by the end of her first year.

“Honestly, the people in my opinion that left, they weren’t on board,” she said. “They were never going to get on board, no matter what I said or did. That’s a battle I didn’t have to fight. They left, because of the accountability and the monitoring.”

In addition to the powers granted to Cash through receivership, the law also mandates regular meetings of a group of school shareholders to discuss how best to meet student needs; at West Hertel, the group boosted in-school teacher training, including on Saturdays; added an afterschool program; and signed up for a $1.75 million grant that gave students iPads.

Owens was also given the ability to enter classrooms unannounced to observe classroom instruction — something the contract would normally forbid.

In the last year, Elia has visited West Hertel twice: once before Cash started as superintendent, and again in March. The commissioner said she was impressed by the school’s increased attendance rates in that short time, but emphasized that the battle to turn around West Hertel and other struggling schools is far from over.

“This is not something that happens overnight, and it takes patience and a focused approach to keep all of the things in place that are being successful” and to alter strategies that aren’t working as well, Elia said. “It’s certainly going to take multiple years, but I think they’re on the right path.”

Capozzi said receivership could be good for the school, even though it has made some teachers nervous or angry.

“You’ve got to be willing to change, and roll with the punches,” the West Hertel teacher said, adding that although teachers may not agree with all of the changes that are being made, “I would say that 99.9 percent of the population would like to see student success.”

Samuel Radford III, the president of the District Parent Coordinating Council of Buffalo, taught his kids at home for three years to escape a school system he calls “completely unfair” for the city’s black residents. The schools Radford’s children attended, he said, were run like prisons.

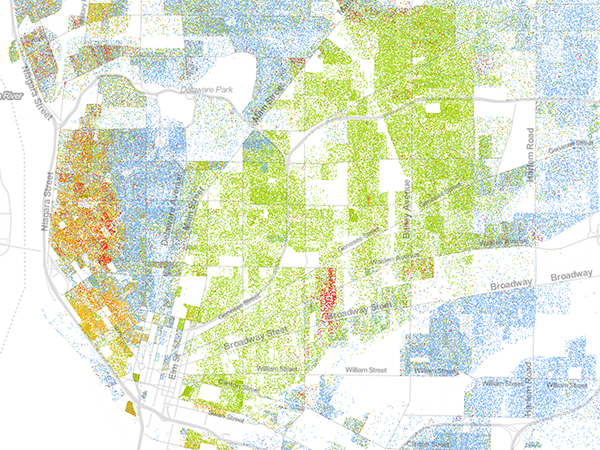

The inequality in Buffalo’s schools system was defined in part by Main Street, a long thoroughfare that for decades divided the city’s neighborhoods by race and class. To the east, residents were predominantly black, while white neighborhoods traditionally clustered to the west.

The city became more diverse in recent decades but not more integrated. Whites moved north or out of the city. Hispanic neighborhoods took root near the lake, along with the city’s growing Burmese, Somali, and Nepali populations.

The greater Buffalo area was among the most segregated housing markets in the country, according to the 2010 Census. The city is also among the nation’s poorest; about eight in 10 Buffalo school children are economically disadvantaged.

Three decades ago, The New York Times described efforts to desegregate Buffalo’s schools — following a 1972 federal lawsuit that found city officials had intentionally segregated them — as a model for the nation.

Those efforts included the creation of magnet schools and an extensive busing system that created greater racial balance across the system. By the early 1980s, about 30 percent of Buffalo students were being bused to schools in neighborhoods where they didn’t live, according to a 2014 report by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The best thing that’s happened to Buffalo is court-ordered desegregation,” then-superintendent Eugene Reville told the Times. “We’ve restored confidence in Buffalo public schools.”

But the high didn’t last. Amid “severe white flight” and budget shortfalls, a federal judge terminated Buffalo’s segregation order in 1995, ruling the city had satisfied its obligation.

With the order lifted, the district’s desegregation goals were abandoned.

By 2012, school segregation had climbed to levels comparable to the early 1970s, with lower-income students attending schools that had higher student mobility and less-experienced teachers.

A Buffalo News analysis found that 70 percent of the city’s schools had minority enrollment of 80 percent or more, a disparity created by housing patterns and an underrepresentation of minority students at schools with academic admissions criteria.

Cash’s theory of action — which he calls his “New Education Bargain” for revamping the entire system — extends to the criteria-based schools as well.

Emerson School of Hospitality, on Chippewa Street in downtown Buffalo, for example, is rigged with a full-service restaurant and a commercial bakery — a model for career and technical education programs that Cash said will prepare students for new jobs in the city’s rebounding economy.

The student bakers and aspiring chefs who arrive at Chippewa every morning are probably unaware that their school is near the heart of what once was Buffalo’s red-light district. Nearby streets were lined with strip clubs and sketchy hotels, and parents were hesitant to send their kids there even during the day.

The racial division in Buffalo’s classrooms is reflected on the school board. While the black members generally side with the teachers union, the white members across the table back reform.

“What happens is that people are fighting for the interests of their constituencies, and our constituencies are broken down by race,” Radford said. “There’s a lot of things that the good old boys club is perpetuating that is making it hard for minorities and poor people to be part of the change.”

During the 2014 school board elections, the board’s continual public bickering helped drive more than twice as many voters to the polls as in previous years, with (a still-modest) 13 percent of Buffalo’s electorate deciding who would lead its public schools.

Voter frustration remains so strong that a high school student says he is compelled to challenge Paladino for his seat this year, arguing the board needs “some adult behavior.”

But special interest groups may have more of an effect on this year’s results than voters.

As the campaign headed into its final weeks, the petitions of 10 of the 12 candidates were challenged, several by the state teachers union, and lawsuits alleging election fraud were filed against three pro-reform candidates — including Sampson, the board president — according to a report by the Buffalo News.

Sampson was subsequently dropped from the ballot when election officials, responding to a petition challenge from a colleague of his opponent, determined he failed to secure the necessary signatures.

Sampson can ask a state court to override the decision, but must do so by Monday.

Crystal Peoples-Stokes, a Democratic New York State Assemblywoman from Buffalo, said the influence special interest groups have on school board elections led her to propose legislation last year to give Buffalo’s mayor power to appoint board members.

“It’s kind of hard to hold a school board accountable for something when they get elected in May and very few people turn out for the elections,” she said. “If the mayor was able to appoint the school board members, then the mayor could be held accountable for what comes out of the schools.”

Her bill failed to gain traction in Albany. She continues to believes mayoral control is necessary, but is more optimistic about the future with Cash in the driver’s seat.

“I think he could totally turn around the district in five years,” she said. “If people let him do what he has planned.”

Donning hats and gloves to keep out Buffalo’s frigid winter air, clusters of teachers with picket signs paced back and forth past the columns marking the entrance to City Hall.

“A NEW CONTRACT NOW,” one sign read. “SMALLER CLASS SIZES = QUALITY.”

Linda Mauras, a bilingual kindergarten teacher at Herman Badillo Bilingual Academy, was among the crowd marching outside.

“If we don’t stick together,” she said, “we fall apart.”

Mauras said the state receivership law is unfair because it allows administrators to “pretty much do whatever they want.” She said she was worried fewer teachers would be willing to work at Buffalo schools because of the chaos.

“They can cut staff, they can add more faculty meetings,” she said. “We put in a lot more hours than we get paid for as it is.”

The protesting educators marched across the street and gathered in Niagara Square to hear teachers union president Philip Rumore speak. Just days earlier, the union filed suit in the state Supreme Court with their parent union, the New York State United Teachers, in an effort to stop Elia and Cash from using the state receivership law, arguing the new rule strips teachers of their collective bargaining rights.

“This has national implications, folks, national implications and we’re not going to stand by, we’re going to challenge this all the way up to the Supreme Court if we have to because that means that contracts are meaningless,” Rumore told the crowd. “Go to some of the southern states where they have that so-called ‘right to work,’ I call them ‘right to be exploited’ states.”

The lawsuit alleges that Elia didn’t consider whether Cash negotiated with the union in good faith before he asked for the state to intervene, and that she refused to consider the union’s proposals to fix Buffalo’s struggling schools, such as smaller class sizes.

Rumore also characterized using state tests to identify struggling schools and students as “child abuse.” He said the test is so flawed a governor’s task force recommended teachers’ ratings based on student test scores be placed on hold until 2019.

“Folks, they have offered us garbage,” Rumore told the teacher protesters. “What they’ve offered us is an insult.”

At the root of the struggling schools’ problems, the lawsuit argued, is poverty — a notion Cash dismissed.

“You can still be responsive when your child asks a question at two and three years old,” Cash said. “Don’t say ‘shut up and go away, I’m watching my program.’ Say ‘OK honey, what is it that you asked me?’ And then answer it.”

As for the lawsuit, Cash said he sees it as a test.

“I’ve been in this business 30 years, we’ve got to keep working, got to keep working,” he said. “Let’s find out what the power and the extent of this law is, how serious New York is about changing chronically underperforming or failing schools.”

Board member Paladino said that while he favors receivership, he believed the judge will overturn the law because it conflicts with provisions in the Taylor Law, which governs labor relations in New York.

“The tail is wagging the dog, the patients are running the asylum,” he said.

For years, the contract with Buffalo teachers has been criticized as an example of government excess. Included in its health insurance package is a plush perk: free cosmetic surgery.

Plastic surgeons advertise In the Provocator, the union’s official publication, offering everything from skin cancer treatment to body contouring, facial rejuvenation, and laser tattoo removal.

In past years, the cosmetic surgery rider has cost Buffalo taxpayers more than $5 million.

The teachers union did not respond to several calls for comment.

“The contract is so good,” Radford said, “It wouldn’t be wise” for the union to negotiate a new one. “They’re never going to get a new contract with a cosmetic rider and 100 percent of health care.”

The district’s contract proposal does call for the cosmetic surgery rider to be eliminated, and Rumore has suggested he might be willing to cut the benefit.

The district’s proposal would also require active school employees to contribute a 10 percent health insurance premium, add a 10 percent increase to the salary schedule, modify the school year from 186 to 188 days, and add 40 minutes to the school day, among other changes.

While Cash said he and Rumore need to sit down one-on-one to hash out their differences, Radford said receivership is likely the only thing that could make the union budge.

“It forces them to negotiate,” he said, “or lose schools and lose teachers.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)