The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit Is Long Overdue for Reform

With a budget debate looming, here are some of the proposed solutions on the table.

Join our zero2eight Substack community for more discussion about the latest news in early care and education. Sign up now.

You’d be forgiven for having trouble keeping up with the alphabet soup of family-related tax credits. Most of the policy attention has rightfully been on the child tax credit (CTC), which is typically a credit parents claim that provides general assistance for child-rearing and is claimed by 93% of taxpayers with children. This tax credit is often used for essentials like food, diapers and clothing, or to pay off debt, though it can also offset the cost of child care. However, there is also an important conversation happening around the child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC). This is a totally separate tax credit that allows working parents to get a break on their taxes based on a percentage of what they spend on the care of eligible children and adult dependents. As Republicans prepare their budget reconciliation package, CDCTC reforms have been put on the table — and deserve the attention of early childhood stakeholders.

A Brief History of the CDCTC

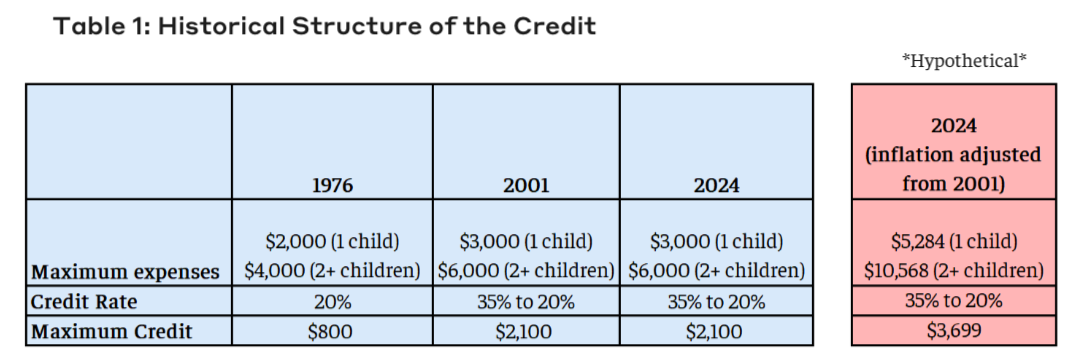

The origins of the CDCTC track back to 1954, when a very limited deduction was introduced for child care expenses. According to a compendium on tax expenditures prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), “The provision was intended to recognize the similarity of child care expenses to employee business expenses and provide a limited benefit.” That deduction was converted into the CDCTC in 1976, as mothers were flooding into the labor force and the nation had no publicly-supported child care system for them. There have been periods of reform since then, but the credit has been stuck in the mud for more than two decades: It has been $3,000 for one child and $6,000 for two or more children since 2001. Without adjustment for inflation, its power has become badly diluted, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center. There was one exception, which was a temporary pandemic boost in 2021 which had a significant impact for many working families. (That boost increased the average credit award by more than $1,500 and led to almost 3 million more families claiming it).

As a result, the average credit per family falls between $500 and $600, meaning their tax liability is reduced by that amount. Reducing the taxes one owes by a few hundred dollars is not nothing, but hardly enough to make much of a dent in child care costs, which commonly run in the thousands and can easily tip into five figures.

The Good

The CDCTC’s strongest suit is how it functions as a broad vehicle to defray child care costs. (Families can claim the CDCTC to offset the cost of care for a spouse or adult dependent with a disability, but CRS notes that it is used “almost exclusively” for child care.) The credit has become especially key for middle-income families since there is no other federal government mechanism to support them with child care costs; all other federal child care assistance is targeted to low- and moderate-income families. Middle-income families heavily use external child care programs, yet they fall into something of a “donut hole” — they often make too much money to qualify for public assistance, but not enough money to be able to comfortably afford programs’ sky-high prices. Absent a strong universal child care system, the CDCTC (or some variation thereof) is necessary to provide some relief.

The CDCTC is also fairly inclusive. While one needs the taxpayer ID of the individual or program used to provide care, the provider can be nearly anyone other than a parent, meaning that it is not limited to licensed care providers.

The Bad

The CDCTC offers important support for many families, but the design is car-with-a-fat-tire clunky. The IRS guidance on claiming the credit is 20 pages long. There are a number of elements including eligibility criteria, extensive rules around earned income, work-related expenses and filing a joint return, and a provider identification test. It is, in short, not an easy credit to claim. Only 12% of taxpayers with children utilize it.

Moreover, the credit does nothing to support broader systems-building in child care. The fundamental problem is that there is not enough public money in the child care system, so it exists as a failed market with high costs for parents, low pay for providers and scarce supply. The government alleviating a sliver of a families’ expenses during tax season leaves the structural issues completely untouched. On a philosophical level, it keeps child care support in the realm of fiscal tax policy as opposed to being seen as essential social infrastructure.

The Ugly

The CDCTC is strongly regressive, meaning that the benefits flow disproportionately to more affluent families. “Currently, nearly 44% of tax returns that claim the CDCTC come from families with an AGI [adjusted gross income] over $100,000; only 6% of returns from households making under $25,000 a year claim the credit, despite those households accounting for 33% of all returns,” writes Elise Anderson, a researcher and policy analyst at Capita.

One reason for the huge disparity is that the CDCTC is non-refundable, meaning that a parent needs to owe a particular amount each year in order to receive the full credit. In other words, if a household has no tax liability — which is true for the majority of parents in lower-income households due to the standard deduction and other credits — they don’t get any benefit.

Finally, the CDCTC categorically excludes stay-at-home parents; families that do not have both parents working outside the home may not claim the credit. The ostensible logic that the CDCTC is a credit to defray tax liability for parents in the labor force doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Families with a stay-at-home parent contribute income taxes by filing jointly, and the labor of many stay-at-home parents enables a spouse to work, particularly if one parent works a job that doesn’t lend itself to regular, predictable hours, like an electrical lineworker or a firefighter who works on wildfires, for example.

What Ideas Are Being Proposed?

There is a reasonable argument to be made to just merge the CDCTC into a broader child tax credit and simplify the whole system. However, that is not realistically on the table at present. Instead, there are a few different reform options being proposed:

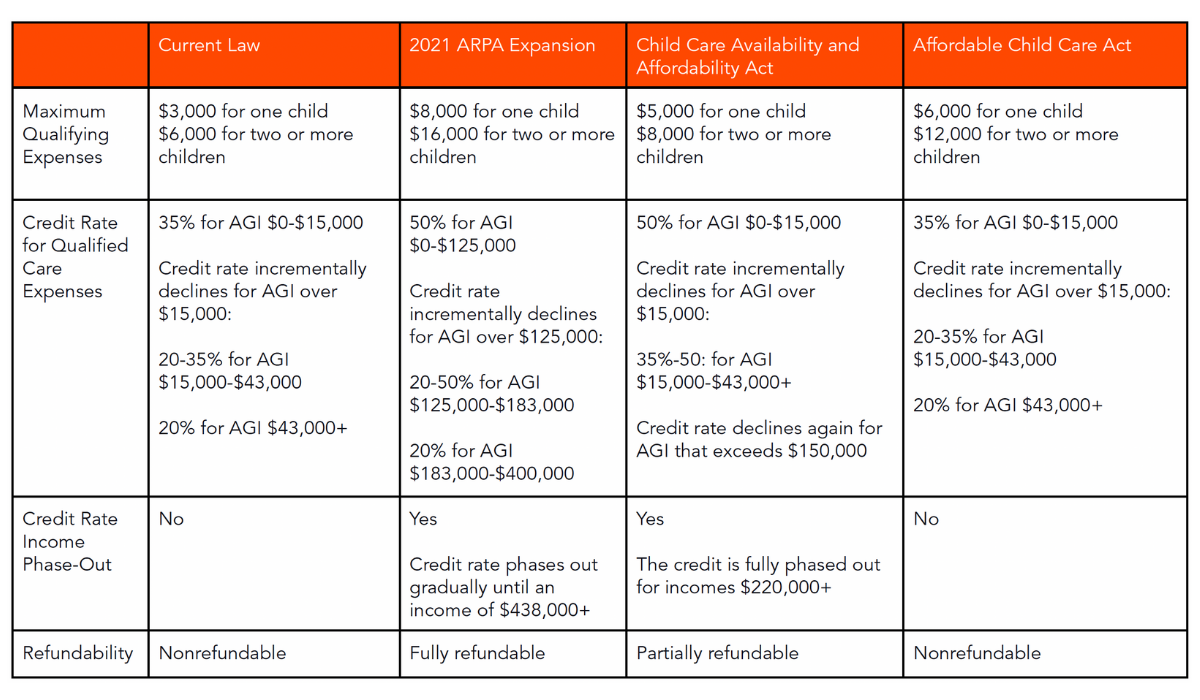

The most relevant proposal, due to the profiles of its sponsors, is the Child Care Availability and Affordability Act. The legislation was introduced in early March by a bipartisan group led by Alabama Republican Sen. Katie Britt and Virginia Democratic Sen. Tim Kaine, and New York Republican Rep. Mike Lawler and California Democratic Rep. Salud Carbajal. It has endorsements from groups not always seen together such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the American Federation of Teachers. Britt is pushing hard to see the legislation folded into the Republicans’ budget reconciliation law.

If passed, the maximum amount of expenses that a family could claim would increase to $5,000 for one child and $8,000 for two or more children. It would also make the CDCTC partially refundable, meaning that a portion of it would go to families even if they owe no taxes, and lower-income families would have access to a larger credit. In practical terms, a family with one child with an adjusted gross income of $15,000 would be able to claim a credit of $2,500 on $5,000 worth of child care expenses and have that amount refunded if they did not owe taxes. Under the current law, that same family with the same expenses can only claim $1,750 and none of it is refundable.

Whatever policy, if any, ultimately ends up making its way into the budget reconciliation package, the CDCTC is long overdue for reform. Child care stakeholders would do well to spend some time getting acquainted with the different plans so they can fully engage in the upcoming debates.

Disclosure: Elliot Haspel is a senior fellow at Capita.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)