The Certification Maze: Why Teachers Who Cross State Lines Can’t Find Their Way Back to the Classroom

But her record wasn’t quite good enough to meet New York state’s stringent licensure requirements.

Because her training was out-of-state and in statistics, it didn’t conform to the strictures for required math courses set out by the New York State Education Department. Franz was forced to pay out-of-pocket to attend night courses in math at a local college to maintain her license. She said the classes didn’t help her much as a teacher and were at a far lower level than the classes she took in Pennsylvania to earn her master’s.

The process was draining, both financially and time-wise, as she was also teaching full time and had personal obligations: “I was about six months pregnant at the time … It was horrible.”

The difficulty in transferring teacher certification is not limited to New York — as Franz learned when she subsequently moved to California and had to navigate that state’s process. Some states, including New York, have recently moved to ease the process.

The issue of teacher licensure reciprocity usually doesn’t draw big headlines or much political engagement, but research evidence, surveys, and interviews suggest that teachers are often limited in their ability to move between states — often for little good reason and to the detriment of student achievement.

Franz’s story ends well but followed a winding road. A Los Angeles public school wanted to hire her but could do so only as a long-term substitute until her certification cleared, which happened only after three months of confusion about whether she had to apply online or with a physical copy. She even served as a volunteer at her new school while waiting weeks for her substitute’s license to go through.

Franz said that after arriving in California, she nearly had to take a job at a private school even though she wanted to work in public education. Substitute jobs don’t offer benefits, and Franz was only able to wait out the certification process because she was eligible for health insurance through her husband’s job. Otherwise, she said, she probably would have ended up at a private school that didn’t require certification. California seems to have a relatively straightforward path to reciprocity — but even then, the uncertainty and time almost cost her a job at a public school.

Other teachers are not so lucky. When Aimee Kocher moved to New York City after three years of teaching early-childhood education in Pennsylvania, she immediately started looking for jobs. She quickly found a school she thought was a great fit and a principal who wanted to hire her.

To get the job, however, she needed to be certified and to get licensed in New York — she was already certified in Pennsylvania. First, though, she needed to decipher which requirements applied to her and then pass a battery of expensive exams. The Pennsylvania certification test that she had successfully passed wasn’t the one used by New York.

Kocher said she initially submitted four separate certificate applications because she wasn’t sure which ones she would qualify for, and has since been granted two “initial conditional” certifications. To get them, she had to pass four separate tests, costing more than $500 in total. To obtain her “initial” license, Kocher will also have to pass an exam called the EdTPA, which costs an additional $300.

“That process [to get certified] was complicated and confusing and still is,” she said.

Kocher ended up working for a year at a charter school, which has more flexibility in hiring non-certified teachers.

“The job that I was excited for — that was very similar to the position that I had in Pennsylvania — I’m pretty sure I would have gotten that job, had I had my certification,” she said.

Currently Kocher — who has a bachelor’s in elementary education and 30 credits towards a master’s degree — works as an assistant teacher at a New York City private school, a job that does not require certification.

New York changed some of its certification rules last year, creating a simpler path for teachers like Kocher. Now an out-of-state teacher with three years of experience and acceptable evaluations can get licensed in New York without taking the state’s educator exams.

A state Education Department spokesman said in a statement that the state processes applications as quickly as possible with an eye toward attracting and retaining new teachers while making sure they are qualified.

“That’s why the Board of Regents acted last year to adopt new regulations that make it easier for qualified teachers from other states to obtain their certification here,” he said.

Meanwhile, teachers moving to Minnesota have found an especially Kafkaesque certification process waiting for them. Despite specific directives by the state legislature to make reciprocity easier, out-of-state teachers have found it nearly impossible to receive a license there without starting an entirely new training program.

As The 74 reported last year, Kirsten Rogers had 12 years’ experience teaching in Utah, but when she moved to Minnesota, she was granted only a two-year temporary license. To get a full credential, she would need to attend — and pay for — additional classes. Her story was not an outlier, and she and other teachers have filed a lawsuit against the state.

Since then, the legislative auditor’s office has issued a critical report of the state’s certification procedures: “The poorly defined terms, exceptions, and frequent changes in law make Minnesota’s teacher-licensure system complex and confusing.”

The state Board of Teaching was held in contempt of court for failing to follow a previous order making it easier for teachers moving to Minnesota to get certified. The lawsuit from out-of-state teachers continues to wind its way through the legal process, after an attempt to dismiss the suit was rejected by a state appeals court in August 2016.

A handful of states, including Arizona and Florida, issue certifications to out-of-state teachers with relatively few requirements. One state, Delaware, grants reciprocity based solely on evidence that a teacher was effective in his or her past position.

The National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification has compiled certification agreements between most states in the country. They are not reciprocity agreements but simply a collection of the (often obscure) requirements for moving teaching credentials from state to state.

Some of these rules seem reasonable in theory but in practice may serve as a strong deterrent to remaining in the profession. Many states, like New York, allow for easier reciprocity for teachers with three to five years’ experience — but this requirement may restrict entry since people are often most mobile earliest in their career.

Even when the process is not all that burdensome, it can be difficult to navigate, with state departments of education sometimes giving unclear or contradictory information. States have a dizzying array of certification types: initial, interim, emergency, professional, conditional, master, temporary, transitional, internship, supplementary. In many places, state websites are bewildering.

“We struggled with that,” said Chris Koch, the former state superintendent of Illinois, pointing to budget cuts. “It’s hard sometimes to talk to a person.”

Research shows that state borders can and do prevent teachers from switching schools across state lines.

One study looked at the Washington-Oregon state line and found that “even among school districts near the state border, almost three times as many teachers make a within-state move of 75 or more miles than make any cross-state move.”

The researchers note that this may be caused by licensure rules as well as the lack of pension portability and the benefits of maintaining seniority in the same state. The paper argues that such policies are harmful: “Barriers to mobility might exacerbate teacher shortages and increase attrition from the profession.”

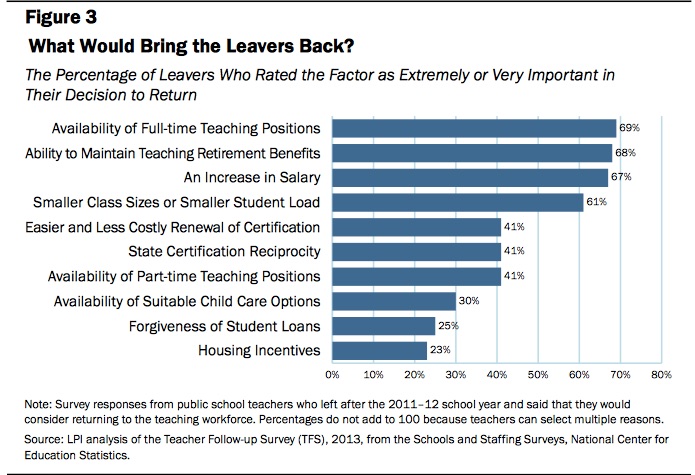

Surveys of teachers also appear to confirm that the obstacles are real. Some 41 percent of former teachers who would consider returning to the profession cited “state certification reciprocity” as very or extremely important in their consideration, according to an analysis of federal data conducted by the Learning Policy Institute. That percentage is higher than in 2005, when about 35 percent of teachers gave that as a reason.

The survey allowed teachers to choose more than one factor as playing a major part in any decision to go back to the classroom, and reciprocity was not rated among the top four. On the other hand, it’s likely that the percentage would be much higher among former teachers who had since moved to another state.

Certification rules seem to be a pain for teachers, but does that matter to students? It’s hard to prove, but the best evidence suggests so.

A recent study found that districts near state boundaries had lower student achievement compared with other districts not near a state border. The researchers looked at districts across the country, finding negative effects of being near the border between two states in both reading and math. Although they couldn’t definitively show why, the authors argue that restrictions on teachers moving between states, because of licensure and pension rules, likely weakens the talent pool and the effectiveness of those hired.

Cory Koedel, co-author of the study and an associate professor at the University of Missouri, said that the results are what would be expected from “basic economic theory.” He gives the simple example of two nearby high schools in different states. They each need exactly one science teacher, but one of the high schools has two science teachers and the other has none. Ideally, the second school would be able to hire the second teacher — everyone wins. The second school fills a vacancy, the teacher gets a job, and the first school is no worse off. But if certification policies prevent the teacher from moving easily, the second school is left without anyone to teach science.

Other research shows that students benefit when teachers are a good fit in their specific schools; licensure restrictions could make this less likely.

Koedel is confident that the negative effects of attending a school near a state border are real, but he notes that they are not especially large.

“The results are highly robust, but they are small,” he said.

These cumbersome requirements appear relatively unique to teaching.

A report from Third Way — a centrist think tank that has generally backed education reform policies — argues that teachers have a particularly difficult-to-navigate route to get licensed, compared to other professionals, such as lawyers.

Twenty-five states have adopted a uniform bar exam that can be transferred across those states. Similarly, 25 states use a single license for nurses. All 50 states use the same certification exam for architects. Accountants have a uniform exam, and most states have adopted rules to make it easier for CPAs to work across state lines. Journalists don’t have licensure or certification rules and can freely move from state to state in their field.

Without a thorough review, it’s not clear if other professions encounter many of the same bureaucratic snafus that teachers seem to when moving between states. Moreover, there’s not strong evidence on whether other occupations’ reciprocity rules have successfully increased interstate mobility.

One study showed, surprisingly, that the Nurse Licensure Compact, which was designed to make practicing across state lines easier, produced “no evidence that the labor supply or mobility of nurses increases following the adoption of the [compact], even among the residents of counties bordering other [compact] states.” The paper did find suggestive evidence that younger nurses may be more likely to move between states because of the compact.

Still, it is clear that many other professions have more-streamlined paths across a number of states, and in some cases all states.

So why do many states put in place such onerous requirements to become a teacher?

One explanation is both substantive and provincial. Koch, the former Illinois superintendent, said that interstate reciprocity should be easier but that, as head of Illinois schools, he wanted to ensure the quality of any out-of-state teachers.

“There were [teacher training] institutions in neighboring states that did a really poor job,” said Koch.

Kate Walsh, head of the National Council on Teacher Quality, argues that states should require out-of-state teachers to pass their licensure exams, since, in her view, it’s too easy to become a teacher in many places.

“We want to make sure that states test teachers who are coming from out of state, so they know their subject matter,” she said. “They often are coming from a state where the cut score on the test is too low or they use a really bad test.”

One problem with this view that there is only a modest relationship between someone’s ability to do well on a certification test and their performance in the classroom. Some have argued that this is because paper-and-pencil exams are inadequate, but even the EdTPA, a performance-based assessment, has limited value in assessing teachers’ contributions to student achievement, according to a recent study.

There is also evidence that onerous requirements for entry into the profession are particularly likely to drive away high-achieving college graduates and prospective teachers of color.

Transcript reviews — the process by which a state board examines a teacher’s transcript or even past class syllabi to determine if they meet certain standards — seem even less defensible. Studies have not consistently shown which types of teacher training are effective and which aren’t.

And in practice, the rules can border on the absurd — such as requiring statistics teacher Franz to take extra classes in geometry, because her statistics courses didn’t count.

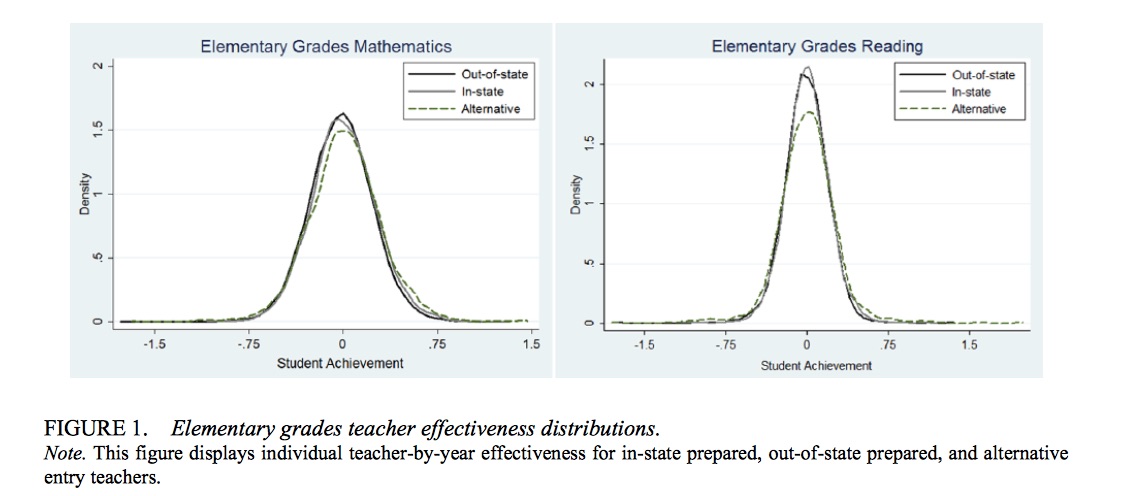

One study does gives some credence to the notion that out-of-state teachers might be less effective. Specifically, research in North Carolina found that teachers trained out of state performed worse and had higher turnover than teachers from North Carolina–based programs. However, the difference in performance was very small. As the study put it, “There is a substantial overlap in the distributions of effectiveness across groups.”

The researchers caution against blanket limits on out-of-state teachers: “Blunt policy instruments, such as eliminating reciprocal certification, that may block many highly effective out-of-state prepared teachers and cause further teacher shortage concerns are not effective responses.”

National teachers unions have taken some steps to address the issue. Both the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association have backed the system of National Board Certification, an advanced credential, that in many places entitles out-of-state teachers to easy reciprocity. However, only a very small share of teachers are nationally board certified.

The AFT has also called for a bar exam–style test for teachers that would serve as a “universal assessment process for entry” into the profession. It does not appear that the NEA has taken a public stance for or against reciprocity. Neither union responded to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, state-level political interests can stand in the way. In Minnesota, for instance, the state teachers union and a coalition of colleges of education have opposed efforts to streamline the process for out-of-state teachers.

Still, there has been progress of late. “We’ve seen more states than ever that consider themselves full reciprocity states. Ten years ago you would never have states that say that,” Phillip Rogers, head of the National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification, told Education Week in 2015.

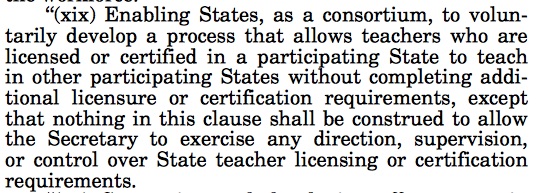

In 2016, a proposal, modeled after the Third Way report, was introduced in Congress to help unify processes across states, though the legislation hasn’t gone anywhere yet. However, a provision was included in the Every Student Succeeds Act, the federal K-12 education law, allowing states to use federal money earmarked for increasing the ranks of high-quality teachers and principals to set up an interstate system of reciprocity of the sort envisioned by Third Way.

Still, Koch, the former Illinois superintendent, thinks a national fix is a long shot: “It won't happen because of states’ sovereignty.”

Koch, though, now leads the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), which he sees as part of the solution. The group grants accreditation to teacher prep programs based on standards designed to ensure quality.

Koch thinks that reciprocity should be granted to any teacher who has graduated from a nationally accredited teacher training program. “If we do our job well at CAEP — and I think we can — coming from an accredited institution would mean that states can trust that any graduate from an accredited university would be able to do their job,” he said.

In some ways, reciprocity is perhaps a symptom of a larger problem: Since there is no widely agreed-upon definition of quality teaching — or how to measure it, how to prepare someone to teach, and how to ensure that a prospective teacher will be effective — it’s no surprise that 50 different states can’t agree either.

In the meantime, the rules will continue to confuse teachers and likely stop many from being in the classroom. Franz, who now teaches in California, said there’s no way she’ll go through the process all over.

“If I move back to New York, I probably won’t be teaching in a public school,” she said. “I can’t do it again.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)