The California School Safety Officer Accused of Murder Wasn’t a Cop. Does that Actually Matter?

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The arrest of a former school safety officer on a murder charge in California has added a new dimension to the debate over school-based policing a year after George Floyd’s death prompted some districts to pull cops from campuses.

This time, the conversation has centered on an armed Long Beach Unified School District safety officer accused of fatally shooting an unarmed 18-year-old girl as she fled in a car near the high school where he worked. The safety officer was once a police officer, but at the time of the shooting, he was working directly for the school district handling security and did not have the status of a sworn school resource officer employed by the police department and assigned to Long Beach schools. School policing proponents were quick to highlight the distinction and advise educators against arming school staff who lack badges.

But civil rights advocates said said the difference is meaningless and the case reinforces a need to eliminate school security officers who serve police-like functions and carry guns.

After the shooting, the National Association of School Resource Officers sought to set apart school-based police from safety officers, noting in a statement that the trade group “strongly recommends that armed personnel on school campuses” be sworn law enforcement officers who are “carefully selected and specifically trained in school-based policing.” The group, which offers a training course for school resource officers, has advocated for armed officers but opposes policies that allow teachers and other school staff to carry guns — a scenario that is often put forth after mass school shootings.

Mac Hardy, the association’s director of operations and a former school-based officer in Alabama, said the stress of carrying a gun inside a school “took years off of my life.”

“Every day, I put on that gun belt to wear inside the school and knew I was going to be in a school with 3,000 adolescent children and another 200 staff members. It was a lot of pressure,” he told The 74, explaining that he underwent regular firearms training. “It’s a huge responsibility to carry a weapon and we just believe it’s best that a trained law enforcement officer carries the weapon.”

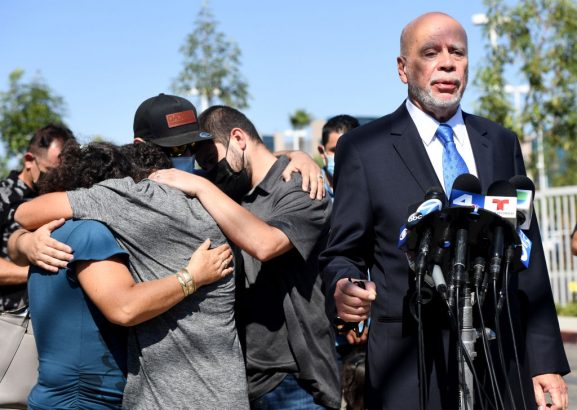

The since-fired Long Beach safety officer, 51-year-old Eddie F. Gonzalez, was arrested Oct. 27 and charged with murder in the shooting of Manuela “Mona” Rodriguez near Millikan High School a month earlier. Gonzalez was reportedly patrolling an area near the school when he observed a fight between Rodriguez, who was not a student, and a 15-year-old girl. Gonzalez, on the job for less than a year, shot Rodriguez in the head as she rode in the passenger seat of a fleeing car, authorities said. The incident was captured on video and went viral online. The shooting left Rodriguez, the mother of a 6-month-old boy, brain dead and she died Oct. 5.

The district’s unsworn but armed safety officers are required to complete a 664-hour basic peace officer training academy that includes firearms instruction, district spokesman Chris Eftychiou said. They’re also required to complete a firearms course through the Long Beach Police Department twice per year. Gonzalez was up to date on those requirements at the time of the shooting, Eftychiou said in an email. Officers also receive training in de-escalation techniques, how to work with adolescents and suicide prevention, he said.

Though the school safety officers don’t make arrests, they can detain suspects pending a police investigation. Following the shooting, the Long Beach Board of Education voted unanimously to fire Gonzalez for violating the district use-of-force policy. His attorney didn’t respond to requests for comment.

School policing has been a topic of national discussion since Floyd was murdered in 2020 at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, which caused a reckoning on police brutality and led dozens of districts to cut their longstanding ties with police departments. Some districts, including Minneapolis, replaced the officers with unarmed security staff. Some critics have worried, however, that the approach swaps campus police for district officers who serve a similar policing function.

The Long Beach district phased out its school resource officer program in 2020 but local activists have called on education officials to cut ties with all armed security staff and redirect funding to student support services like counselors.

One Long Beach activist, Najee Ali, told a local newspaper the shooting is a deadly example of the harms of armed safety officers “who are one step above a security guard and don’t have the training of a police officer.”

“It’s a recipe for disaster,” Ali told the Press-Telegram. “Unfortunately, Mona Rodriguez paid for it with her life. Until Long Beach Unified takes a second look at these flawed policies, we believe there will be another shooting.”

Eftychiou, the district spokesman, said the school system continually examines its school safety practices and the criminal case against Gonzalez may spur reforms.

“We have also heard from many community members about what school safety should look like going forward,” he said. “We have, and will continue to provide opportunities to listen and engage in critical discussions with our local community and national experts about safety and well-being.”

As districts across the country examine police presence in schools, armed security must be part of the discussion, said Harold Jordan, the nationwide education equity coordinator at the ACLU of Pennsylvania whose advocacy focuses on campus cops. The national resource officer group’s efforts to draw a line between Gonzalez and campus cops is “patently absurd” because school resource officers and school safety officers are “a distinction without a difference.” Both are required to complete peace officer training, carry guns and have law enforcement duties.

“The central element of what led to this young woman’s death exists no matter what his job title is,” Jordan said. “He’s able to carry a firearm because he is a school safety officer with probably the most serious power that an officer — sworn or unsworn — can have: That is the power to carry a firearm and discharge a firearm.”

Jordan said that armed officers — whether they work for school districts or as sworn police — shouldn’t be stationed in school full time and should only be called to campuses during rare emergency situations.

“It creates an inherently threatening environment,” he said. “It sends the message that the kids are the problem there and it increases the expectation that something may go wrong in a school.”

Prior to becoming a district safety officer earlier this year, Gonzalez served as a cop with two nearby police departments between January 2019 and July 2020. Details about his departure from those departments remain unclear, but Eftychiou said he passed a district background check that explored issues such as previous excessive use of force, consistently poor judgment and dishonesty.

Floyd’s murder resulted in some districts cutting ties with police, but another recent tragedy — the 2018 mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida — led some to bolster the presence of armed security. In Florida, a law required school districts to station at least one armed official, including civilians, on every K-12 campus. Some districts created their own police departments and others hired armed “guardians” without law enforcement backgrounds. Several of them have gotten into trouble involving their official duties. In 2020, a Clay County guardian was arrested and charged with stashing cocaine inside his vehicle on a high school campus. A year earlier, police accused a former Pinellas County guardian of pawning his service pistol and body armor for gas money. The allegations came to light following the guardian’s arrest on domestic battery and false imprisonment charges.

After the Long Beach shooting, retired emergency management specialist Ted Zocco-Hochhalter was among those who sought to distinguish Gonzalez from school resource officers. To him, the issue comes down to mentality. Zocco-Hochhalter’s two children survived the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado, but his daughter was left paralyzed after being shot during the rampage.

Gonzalez previously worked as a police officer, but it’s important not to lump in school resource officers with “rank-and-file police officers,” Zocco-Hochhalter said in an interview. Simply having law enforcement experience shouldn’t be enough to get a job inside a school, he said. Though there are no national training requirements for campus police officers, he said it’s critical that officers receive specialized instruction before working inside schools and must approach the job with a mentality that places mentoring and relationships first. Gonzalez’s decision to fire at the fleeing vehicle, he said, suggests he lacked “the proper mentality going into that job.”

“If his first reaction on a fleeing vehicle like that from the scene of a fight was to fire his weapon, that tells me that he was a rank-and-file law enforcement officer before he became this safety officer,” Zocco-Hochhalter said. “That’s what kicked in instead of trying to de-escalate or call for help.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)