The Architect: How One Texas Innovation Officer Is Rethinking School Integration

By Beth Hawkins | September 25, 2018

Mohammed Choudhury: In America’s most economically divided city, a ‘diverse-by-design’ prophet is weeding out segregation, one equity audit at a time

San Antonio, Texas

Mohammed Choudhury grew up in Los Angeles, “a minority amongst minorities.” His parents emigrated from Bangladesh in the 1980s, a moment he sees in retrospect as an easier time for immigrants to establish themselves. His parents saved up, opened a restaurant in West Hollywood, and worked their way into the middle class.

They sent their kids to the neighborhood school, which had students from all over the world, something Choudhury loved. He knows now, as a rising star in education leadership, that it was academically lackluster. But from his parents’ perspective, the school was the gateway to the self-determination they came to the U.S. seeking.

“For my family, and on my dad’s side especially, it was a big deal for us to be educated,” he says. “It was a privilege in Bangladesh.”

Choudhury came to understand that firsthand. In fifth grade, he was taken to visit the village where his paternal grandfather built the first school in 1953. Back then, only children from wealthy families went to school. Otherwise, if you were born in a village, your future was preordained.

“When my grandfather built that school, he basically flipped that concept on its head and said, ‘We can access education here,’” says Choudhury. “I grew up under that upbringing, that it matters. And to me it was more about agency.”

Fast-forward not so many years, and Choudhury, 34, is leading a closely watched effort by the San Antonio Independent School District to open dozens of innovative new, diverse-by-design schools. Because virtually all of the district’s 50,000 students are impoverished, to create that diversity he must both attract affluent families from outside the district and ensure that children from the most isolated, destitute families within it are represented in these exciting new schools.

After decades of shrugging over the seeming impossibility of desegregation, many communities are responding to renewed interest in paying more than lip service to school integration. In this context especially, Choudhury’s work has drawn national attention.

“When I heard Mohammed was joining the team in San Antonio, I wasn’t surprised,” says Mike Magee, CEO of the nonprofit state and district superintendent network Chiefs for Change. Choudhury, he says, is “one of the leading national advocates and experts on creating diverse-by-design public schools as part of an overall equity strategy.”

Half a world away from Bangladesh, San Antonio has repeatedly been named the most economically segregated city in the United States. Its most impoverished communities are not villages, but their geographic isolation and profoundly inequitable school systems have their roots in early decisions to segregate blacks and Latinos on small, dense tracts of land.

There are 17 school districts within the city, catering to communities of differing levels of prosperity. San Antonio ISD serves the urban core made up of those red-lined neighborhoods — which means Choudhury is attempting to integrate schools where more than 90 percent of students are economically disadvantaged, according to the federal definition, and almost all are Mexican-American.

Choudhury’s work, then, is different from what most people envision when integration is talked about. Traditionally, districts that are pursuing desegregation are drawing attendance boundaries and taking other steps to get children of different races and ethnicities into common schools.

It might be on a different continent and a lifetime later, but Choudhury is fulfilling his family’s legacy in creating schools where education can serve as a means to self-determination.

“I am a proud product of an urban school district,” he says. “My family is that story of the American dream.”

Winners and losers: ‘A few winners and lots of losers’

School in California provided Choudhury with the mobility his family hoped for, but it also served him lesson after lesson in how unequally those opportunities are distributed. In high school, he was tracked — sized up and placed in a magnet school for students who were deemed college material.

“I knew there were other tracks that weren’t because I had friends that I hung out with,” Choudhury recalls. While they were taking math classes that didn’t count for anything, he was taking algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. The gap in aspirations made him uncomfortable.

One day, his high school held a career fair where he met a sociologist. “I thought it was the coolest thing that they just study problems,” he says. “You figure out what the underlying root causes were, you promoted a solution or you gave solutions, and you solved it.”

He set his sights on UCLA but didn’t get in. Determined, he bypassed the University of California schools that did admit him and enrolled in Santa Monica Community College, which had a path for feeding students into UCLA. After earning his bachelor’s degree there in English and Chicano studies, he went into the education program to train to be a classroom teacher.

Choudhury taught in several Los Angeles Unified School District schools, helping to turn around Luther Burbank Middle School, a chronically low-performing school that rose to be named a state “School to Watch.” The district’s magnet schools were terrific, but he was frustrated with the lack of opportunity outside of them. He could do more for more kids, he decided, in a position where decisions were being made.

“I said, ‘I need to get into those rooms,’” he says. “And that eventually led me to be obsessed with school design and redesign and with how enrollment works.”

WATCH — Innovation czar Mohammed Choudhury on designing schools for diversity:

In 2014, Choudhury was hired to help the Dallas Independent School District develop 35 new or rebooted schools organized around teachers’ interests. The first new schools were quickly oversubscribed, drawing some 1,600 applications for 617 seats for the 2016-17 academic year.

Inevitably, affluent families flocked to the schools. The district came under pressure to give admissions priority at one — an all-girls engineering-themed school — to children from the surrounding very wealthy neighborhood. No way, said Choudhury. That would simply re-create the segregation wrought by housing patterns.

“One of the things that we told ourselves is we’re not going to do school choice … in a way that exacerbates segregation,” he says. “We’re not going to create a system [that has] our hands and fingerprints on it that allows a few winners and lots of losers.”

Elements for success: Three elements for success

When the district got a new superintendent, Choudhury started looking for his next gig. He was thinking about going to work for the state of Texas or maybe returning to California when he got a call to meet San Antonio ISD Superintendent Pedro Martinez. The south Texas district was a third the size of Dallas, and Choudhury was determined to continue implementing his integration vision.

Motivated by a desire to show teachers and families alike that San Antonio ISD could achieve academic excellence with the poorest, most challenged students, Martinez had already started a gifted and talented school to serve as an incubator of teaching talent and opened it to children of any ability. Choudhury sensed a kindred spirit.

“One of the things, if he was going to pick me, diverse by design was going to happen,” says Choudhury. “That’s non-negotiable to me. He was like, ‘Absolutely.’ He grew up in Chicago, he understands how things played out in the magnet schools.”

Martinez, in turn, was attracted to Choudhury’s insistence that school choice must be accompanied by mechanisms that ensure equitable access for all families, something he wishes had been in place during his time in Chicago.

“It gives me a lot of comfort to know there is someone watching out for that who shares my values and is so passionate,” says Martinez. “Often, when district leaders discuss choice options, there are unintended consequences for parents, and Mohammed is dedicated to understanding families’ needs.”

Martinez says his chief priority for Choudhury is the creation of systems. “The longer strategy that will take some time is taking these strategies and replicating them,” he says, explaining that Choudhury’s brand-new Office of Innovation will oversee this.

“I believe Mohammed’s leadership is already showing those changes,” Martinez says.

Three elements are indispensable in creating a system of schools that’s equitable and sustainable, in Choudhury’s view. The first is schools with attractive themes or instructional models, such as Montessori or dual language, in accessible locations. Then there’s transportation; without busing, the most desirable schools will fill up with families that can transport their own kids.

Finally, districts should create one unified enrollment system and use it to weight enrollment at each school for diversity. Families that don’t get their first choice in a computerized lottery should get help finding the next-best fit for their child, and the admissions process should include equity audits to ensure that the most isolated students are adequately represented.

He’s right, says Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which in February invited leaders from 16 cities around the country to visit San Antonio and learn about Choudhury’s and Martinez’s work.

“When there is more choice in a community, there is always a risk of sorting and segregation,” she says. “Cities that I have seen that have taken enrollment challenges really seriously have done the hard work of going out and doing that kind of education.”

Block by block: Addressing poverty, “block” by “block”

Installed as San Antonio ISD’s first chief innovation officer in February 2017, Choudhury picked up a project Martinez had started upon becoming superintendent in 2015. School districts and education policymakers almost always quantify poverty according to the number of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the family income data point collected universally. But that statistic isn’t useful when it applies to virtually every student in the district.

For a family of four, that threshold is $45,500 in most places — nearly twice the federal poverty level and much higher than the $30,000 median income of San Antonio ISD’s families. Using much more nuanced and precise census data, Martinez had created a map listing median family income at all 90 schools in the district. Some were as low as $12,000 a year.

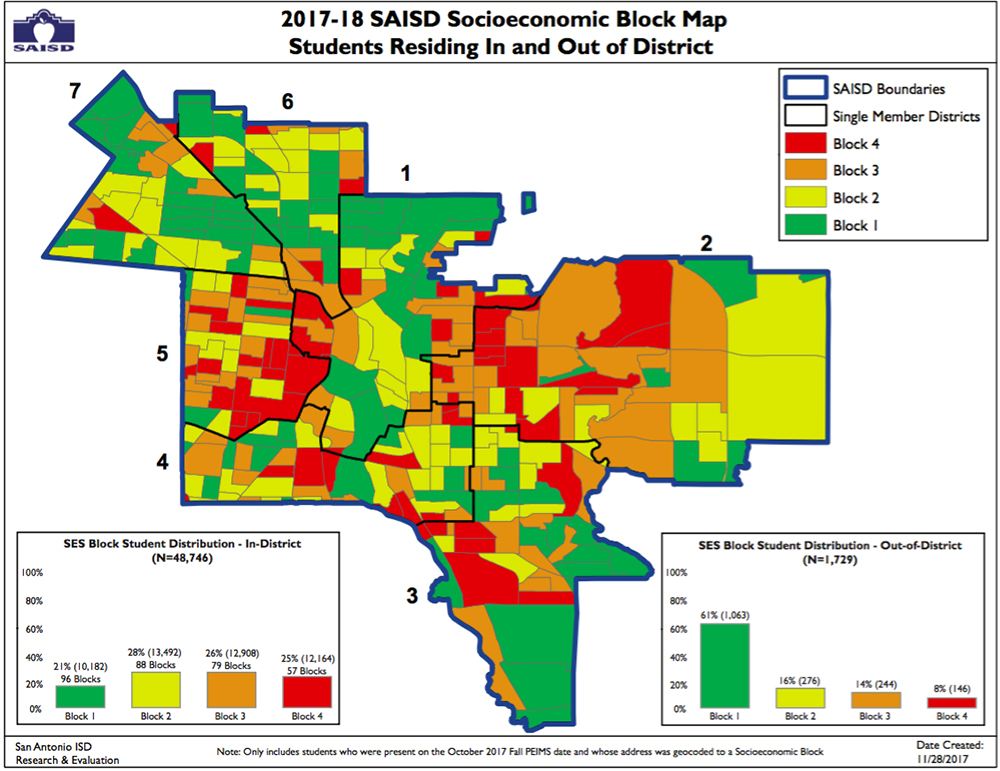

Choudhury mined deeper into the data, layering parents’ educational attainment, single-parent household status, homelessness, and other information into four census income “blocks.”

The gifted and talented school Martinez had launched, Advanced Learning Academy, had a waiting list even before it opened. As the superintendent intended, a fourth of the students were from outside the district. And, as is the case whenever a school acquires a buzz, applications for its second year skewed even wealthier.

Complicating things further, some of San Antonio ISD’s most popular offerings are dual language schools. Many of the city’s Latinos were forced to give up their Spanish because of past beliefs that children should assimilate. The district’s new bilingual schools are to be integrated not just by Choudhury’s socioeconomic blocks but also by home language status.

Similarly, a new Montessori program with a focus on inclusion aims to enroll pupils with disabilities, a particularly underserved population in Texas, which earlier this year was found to have improperly denied services to tens of thousands of special-needs students. In the wake of a Houston Chronicle investigation, the U.S. Department of Education confirmed that state officials had imposed a cap on how many students local districts could classify as being eligible for special education.

Meanwhile, the new, high-tech CAST Tech High School enrolls fully half its students from outside the district. In its first year, CAST earned a state “distinction” designation, meaning it outperforms similar programs.

All of this means Choudhury will need not just to conduct an admissions lottery for each school where there are more applicants than seats, but also to control for other student socioeconomic factors, depending on each school’s desired makeup. Like other districts with centralized admissions systems, his office uses a computer algorithm to run lotteries.

Because district “choice” schools reserve seats for different socioeconomic groups, admissions officers either run multiple lotteries until all seats are filled or, in the case of schools with waiting lists, go down them in numerical order until they find a suitable applicant. The district’s dual language schools, for example, receive more applications from English-dominant households than Spanish-speaking ones and so tend to admit most or all native Spanish speakers who apply.

To preserve the 50-50 home language balance at a dual language school, for example, San Antonio ISD leaders might bypass students atop a waiting list if they are from English-speaking families and instead admit the first student on the list from a family of native Spanish speakers.

Special attention will have to be paid to making sure that children from the poorest census blocks, Blocks 3 and 4 in Choudhury’s system, apply and get in. Poor though they are, families in Blocks 1 and 2 are more likely to have two parents with at least one stable job and to be literate, all factors that make them more likely to undertake the process of choosing a school.

The system is working at CAST Tech, where 71 percent of students from outside the district come from San Antonio ISD’s highest-income “block,” versus a fourth of students who live in the district. Half of CAST Tech’s in-district students come from the more disadvantaged and poorest families, the bottom two income blocks.

The most fragile and isolated parents are not likely to realize they have options or to have the context to analyze them without support.

“The Montessori program we have, one of the toughest battles is convincing them that it’s a school that’s not selective admissions, and their child can thrive in it,” Choudhury says. “It’s going to be a constant battle to shift that narrative.”

San Antonio ISD enrollment staff will fill out applications for families over the phone and regularly set aside time to knock on doors in the poorest neighborhoods. For families who don’t win the lottery, district staff call to let them know about similar schools with open seats or new programs closer to home.

Finally, Choudhury’s system gives extra weight to applications from children attending Texas’s lowest-performing schools, the ones on the state’s “improvement required” list. In 2017, 19 of the district’s 90 campuses were on the list, but 35 would have qualified if new, higher state standards implemented this year had been in force. In 2018, the number of schools on the list fell to 16.

74 EXPLAINS — ‘In 20 years of writing about integration efforts, I’ve never seen anything like this’:

Fighting resegregation: Fighting the resegregation tide

In the decades since court-ordered integration plans of the 1970s and 1980s lapsed, most communities have returned to systems of neighborhood schools, which enroll students according to segregated housing patterns.

One-third of black and Latino students go to schools that are 90 percent or more nonwhite, according to The Century Foundation. The reverse holds true for white children: More than a third attend schools that are virtually all-white.

Meanwhile, as courts have restricted schools’ ability to integrate based solely on race or ethnicity, a number of districts and charter schools have experimented with integrating according to socioeconomic status.

Until 2010, Wake County, North Carolina, had a widely lauded program of integrating schools economically by grouping relatively impoverished schools in Raleigh and more affluent schools from 11 surrounding suburbs into a single large district. The program ended in a political backlash fueled in part by transportation issues, school schedules, and funding disputes.

A similar socioeconomic integration scheme in Kentucky’s Jefferson County, which encompasses Louisville, has remained in force despite assaults from state lawmakers. Some charter schools, which in most places must admit by blind lottery, recruit from diverse communities.

But those efforts have relied on the voluntary participation of wealthy suburbs adjoining impoverished cities. San Antonio ISD, by contrast, is going it alone.

“It may not be perfect out of the box,” says Lake, of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. “But the commitment I’ve seen from that team suggests they’ll keep refining and pushing until they get it right.”

And they will keep pushing, if Choudhury has his way, to make sure the system is successful enough that future leaders would be foolish to water it down.

“What keeps me up at night is that I will not be able to build a system that prioritizes equity that can last beyond Superintendent Martinez, myself and the current board members,” he says. “I have told my team and I continue to tell them, ‘Design as if you won’t be here one day.’ That’s what keeps me up at night.”

T74 PROFILE – One on One with Superintendent Pedro Martinez:

Read other installments of this series, as well as other recent coverage of school segregation and district integration efforts, at The74Million.org/Integration.

Disclosure: The George W. Brackenridge Foundation provided financial support for this project to The 74. | Video Credits: Edited by James Fields; Produced by James Fields, Beth Hawkins & Heather Martino.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter