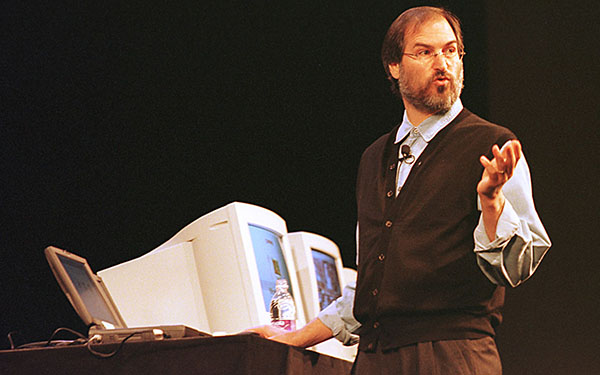

It’s 1997. Steve Jobs, after almost a dozen years in exile, has returned to Apple, the company he co-founded — which has fallen so far from its glory days that its continued existence is not a given. Dressed in a white shirt under a black vest, he’s pacing the Macworld Expo stage in Boston, outlining how he’s going to restore it to health.

Jobs explains that Apple will focus on the few markets in which it’s still strong — one of which is schools. “Apple put the first computers in education,” he declares. “Apple did it again with the Macintosh. And Apple is still the dominant leader in education.” It is, he points out, the single largest education company in the world.

“What an incredible foundation to build off of,” he says. “What an incredible legacy to build off of.”

It’s a memorable moment at a critical juncture for Apple. You won’t, however, find it in “Steve Jobs”, the new movie written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by Danny Boyle. Though based on Walter Isaacson’s 656-page biography, the film consists of only three sequences, each set backstage before a Jobs keynote presentation. His 1997 Macworld talk, important though it was, is not among them.

But when Jobs told the crowd in Boston that education was close to his heart he meant it. From the very start, Apple was intensely interested in the use of its products in schools. That link shaped the character of its products and helped it succeed as a business. Along the way, it permanently changed how learning happens.

The educational use of Apple products reaches all the way back to the very first production unit of the company’s first computer, 1976’s Apple 1. According to lore, Steve “Woz” Wozniak, Jobs’ co-founder, donated that machine to an educator named Liza Loop. She used it to teach algebra at a junior high in Windsor, California. (That particular Apple 1 tended to crash a lot, which didn’t make it any less historic.)

The Apple 1 offered computing in its most rudimentary form, but 1977’s Apple II did color graphics and sound at a time when most PCs did not. It also came with a built-in version of the BASIC programming language, which was designed for use by students. In a BYTE magazine article published shortly before the Apple II went on sale, Woz highlighted education as a primary application for the new system.

It wasn’t that Apple didn’t face competition when it came to classroom computing. (My own high school standardized on Radio Shack’s far less glitzy TRS-80 systems, which meant that my earliest hands-on experience with Apple’s products happened at a local computer store, where I’d park myself in front of an Apple II and mess around in BASIC.) But the Apple II’s video game-like sizzle made it particularly alluring to young people.

And of all the early computer companies, Apple did the most serious thinking about how to get computers into schools. Back then, PCs were sold mostly through tiny mom-and-pop stores which catered to the earliest computer nerds. So in 1979, Apple wisely partnered up with Bell & Howell, an audio-visual giant with decades of experience in selling tech gear to the education market. It offered a custom version of the Apple II Plus with a sealed black case, some additional A/V connectors, and a nameplate which mentioned both Bell & Howell and Apple.

“I came up with this crazy idea … where we tried to give a computer to every school in America”

The same year, Apple established the Apple Education Foundation, which donated hardware to projects aimed at everyone from preschoolers to college students. Just as important, it ensured that its computers could be used for instructional purposes by awarding grants to developers of software for teaching chemistry, foreign languages, chemistry, music, and other subjects.

In Minnesota, an influential organization known as the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium struck a deal to buy Apple II systems in mass quantities from Apple and resell them to state schools at cost, putting thousands of machines in classrooms. It also wrote and distributed Apple II educational software, spreading its influence far beyond the Land of 10,000 Lakes. (Its most celebrated program, a pioneer-living simulation called “The Oregon Trail”, remains available today in a version for the iPhone.)

Minnesota’s efforts may have been a model for the rest of the U.S., but in the early 1980s, many schools still found computers unaffordable. That led Jobs to have a brainstorm. “I came up with this crazy idea that turned into a program called ‘The Kids Can't Wait,’ where we tried to give a computer to every school in America,” he explained in a 1985 Newsweek interview. The crazy idea turned into a federal bill called the Computer Education Contribution Act of 1982, which would give Apple and other manufacturers a major tax break for PC donations.

Even then, Jobs’ powers of persuasion were legendary. To advocate for the bill, Jobs took his show to Washington, D.C. “I actually walked the halls of Congress for about two weeks, which was the most incredible thing,” he told the Smithsonian’s Daniel Morrow in 1995. “I met probably two-thirds of the House and over half of the Senate myself and sat down and talked with them.”

Despite his lobbying, the bill faced intense skepticism. In an unsigned editorial, The New York Times noted that if an Apple II cost $500 to manufacture, the tax break would result in the U.S. Treasury taking a $460 hit for every computer that Apple donated. “If Congress wants to send an additional $460 to every school,” the newspaper tartly concluded, “just send it and let educators decide how to improve the computational skills of their students.”

The Computer Education Contribution Act of 1982 breezed through the House, but never came to a vote in the Senate. But it inspired Apple’s home state of California to enact similar legislation. Apple ended up giving almost 10,000 Apple IIe computers to schools, each worth $2,364.

By the time Apple was ready to release its next epoch-shifting computer, 1984’s Macintosh, it was only natural that education would be part of the strategy. “We…wanted Macintosh to become the computer of choice in colleges, just as the Apple II is for grade and high schools,” Jobs told Playboy’s David Sheff in 1985. “So we looked for six universities that were out to make large-scale commitments to personal computers–by large, meaning more than 1000 apiece–and instead of six, we found 24. We asked the colleges if they would invest at least $2,000,000 each to be part of the Macintosh program. All 24 — including the entire Ivy League — did.”

Macs did become the computers of choice at the university level, helped along by an educational discount program which Apple has offered ever since. That distinction wasn’t a permanent face of life, though, especially as cheap, utilitarian PCs running Microsoft’s Windows came to dominate the market. Eventually, the Macs on campus came to be outnumbered by Dells.

But when Apple came roaring back in the 21st century, education came along for the ride.

Steve Jobs speaks at a 1997 press conference in Cupertino, California. (Photos by Getty Images)

Last year, when the company reported that Mac sales were up by 21 percent — in an otherwise stagnant PC business — CEO Tim Cook specifically called out university sales as one reason why. "I think if you went out to college campuses about now, you would see a lot of new Mac notebooks there," he said.

Of course, today’s Apple is about far more than just Macs. Its tablet, the iPad, is a personal computer by any reasonable definition, and is widely used as a teaching tool at every level. The company even offers iBooks Author, an ambitious publishing program focused on designing richly interactive textbooks for consumption on iPads. Though it hasn’t blown up the market for conventional dead-tree textbooks just yet, the software is a reminder that Apple has never stopped thinking about the future of education.

As Steve Jobs put it back in 1997, it’s an incredible foundation, and an incredible legacy.

Harry McCracken, technology editor at Fast Company, has written about computers since the glory days of the Apple II.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)