Updated Nov. 2, 2016

Editor's note: David Seeley died Sunday, Oct. 30 with his family at his side. Services will be held at 11 a.m. Saturday, Nov. 26 at Christ Church, 76 Franklin Ave., Staten Island, New York. Family and friends are invited to continue celebrating his life at an afternoon luncheon at the family home, 66 Harvard Ave., Staten Island. His ashes will be laid to rest next to his beloved wife, Mae, at Greenwood Cemetery at 10:30 a.m. Nov. 27. Obituaries were published by the Staten Island Advance and the New York Times.

Staten Island, New York

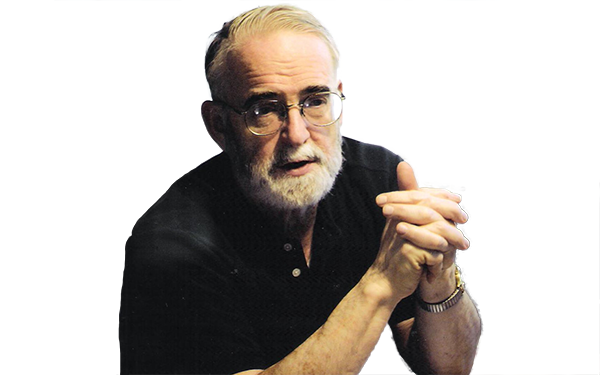

David S. Seeley has been right there for many of the major education battles of the last 60 years. He worked closely with Kenneth Clark, whose earlier, groundbreaking research on the self-esteem of black children was pivotal to Brown v. Board of Education; he was an assistant U.S. education commissioner under President Lyndon Johnson when there was a national commitment to addressing poverty’s ills and implementing desegregation and later served as education advisor to Mayor John Lindsay, weathering anti-war protests, racial unrest and — oh yes — the lead-up to a two-month New York City teachers’ strike.

This educational Zelig of the late 20th century also spent 22 years in the classroom, teaching at the City University of New York on Staten Island. At age 85 and confronting a type of Lou Gehrig’s disease, he now awaits CUNY’s approval for a new degree program, a Doctor of Education in Community-Based Leadership, that he helped develop.

Seeley is the product of some of the country’s most elite schools, although his family struggled financially: Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard (doctorate in education) and Yale (undergraduate and law) universities. He describes himself as an “accidental” education reformer. He raised five children on Staten Island with his late wife, Anna Mae Menapace (a New York City public school teacher who went by “Mae” and crossed the picket line during that 1968 strike). He recently reflected on an extraordinary career at the nexus of academia, public education and politics. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The 74: You went to Yale to become a lawyer. How did you end up devoting your career to education reform work?

Seeley: It all happened by accident, all the way along the way. I never committed myself at any particular point to spend my life on education reform. I just got out of law school and tried it out to see if I could use my lawyer work in some way to deal with the immediate problem of the Jim Crow schools and the South’s defiance of it. So I went down to Washington, D.C., to work as a lawyer at the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, under President Dwight Eisenhower. My work there from 1956 to 1959 focused on assisting with negotiations with local school districts that remained segregated a couple years after the Brown (v. Board of Education of Topeka) decision. I wanted to be a soldier in the desegregation battle.

Speaking of Brown v. Board — the 1954 landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that determined separate schools for black and white children were unconstitutional — it just passed its 62nd anniversary. In the wake of the Brown decision and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, you played a critical role in pushing southern schools toward desegregation as assistant U.S. commissioner of education, from 1965 to 1967, under President Lyndon Johnson. Recent research shows that decades later, racial and socioeconomic disparities in American schools persist and, by some measures, have worsened. Looking back, were your early efforts to integrate the schools successful?

No. It was much more difficult and much slower than I would have hoped for. We did succeed in shifting all of the roughly 2,000 school districts that were announcing they were not going to comply — they called it “massive resistance,” that was their slogan for how they were going to respond to the Brown decision. And (their campaign) was totally effective. There wasn’t a single school district in those 11 states that took one step to desegregate unless they were under a court order. … Total massive resistance. We did shift practically all of them from defiance into compliance, but with very weak desegregation plans.

We didn’t have any staff to investigate anybody (for not complying). Our plan to withhold districts’ funding unless and until they submitted a desegregation plan was later upheld in court. (Over a period of two years) everybody shifted from total noncompliance to coming in with desegregation plans. We got practically all of them to come in with plans, but many made it easy for the “separate but equal” doctrine to be kept alive by leaving integration up to a school’s or individual family’s choice … So we didn’t get much integration going, nor did we convert the Southern people, who I think are still unconverted. They’re right in a resurgence of the old Confederacy today — today, right now, we’re still confronting this. … We’re definitely not past the race problem. Right here in Staten Island, too, it’s gotten worse as a matter of fact.

You moved to Staten Island in 1967, as race riots tore through cities like Detroit and Newark. You and your wife sent your five children to New York City public schools on the North Shore of Staten Island, which was a largely immigrant and working-class neighborhood at the time. You also moved your family to Nigeria for a year, in 1961, while you trained teachers for the Peace Corps. How did your strong support for integration, and your professional experience, shape your approach to parenting your children and making decisions about their education?

We sent them to the local public school here that was roughly half black and half white. They did not get as rigorous an education by far than they would have gotten if I’d sent them to a high-powered private school. They got beat up to some extent, but they also learned to get along with others. And I think they got a good introduction to the racial problem that we still haven’t overcome by any means.

For decades, you’ve advocated for what you call “home-school-community partnerships” as a strategy to confront the problems plaguing our public education system. You’ve called for greater collaboration between the private sector and public schools, more home visits to students’ families, more school volunteers, peer tutoring and cooperative learning, especially in inner-city schools. Your analysis is laid out in your 1981 book “Education Through Partnership.”

These ideas you started writing about in the 1980s were, to a large extent, an early version of today’s “community schools” — in which outside organizations collaborate with schools to provide support services like health care, nutrition, counseling and legal services to students and their families. With the new federal education law returning much of the decision-making authority on K-12 education to states and local districts, the community school concept has seen a resurgence of sorts. For example, New York state recently awarded $100 million to high-needs districts, including $28.5 million to New York City public schools, to turn the most chronically struggling schools into community schools.

What will it take to carry out this strategy successfully?

You can get a lot done without announcing a revolution. But if you really want to get the wraparound (services) to be really effective, it’s not just adding more bureaucracies, providing more non-educational services like health, mental health or employment opportunities for the parents. All that can be helpful. What I think really makes the difference is a collective attitude shift and it means the whole society is mobilized. Everyone shares the responsibility, even if you don’t have kids. If you just run into a kid in the street, he’s our future. Every child that you have in your community, that’s your future and you should really treasure him and try to help him be as successful as possible rather than, “I just want to help my kid, and to hell with everybody else.”

Where has the community schools model been working?

Cincinnati seems to have demonstrated this and Syracuse, New York, to some extent, as well as Lincoln, Nebraska.

You taught graduate and undergraduate education courses, primarily working with prospective teachers, in the City University of New York system for the latter half of your career. What’s your view on the role of colleges and universities in K-12 public education reform today?

I think we should begin to lobby our universities that have full schools of education with graduate students and research capability, that they should add to their mission not just training teachers, which is how they all grew up as teacher training institutions, but act more like the medical schools — the places that do intellectual work, deeper level (work) and looking at the long-term trends over years. The faculty there is enabled to pull back and look at things in a more systematic way and give more advice to the community about what has to be done to get our kids educated successfully.

What’s your advice to policymakers and educators who may be interested in exploring your ideas, or building on them, in their work?

It’s a very big change in culture and it is going to be resisted — I learned that pretty quickly — mostly by the school system and by the parents too. You’ve gotta shift over from your bureaucratic system to a much more collaborative model. People who are used to working in a bureaucracy, they know who they’re working for — people further up the pike. They have to shift their thinking, their focus, to ‘You’re working for those kids and their parents, and they’re the ones you have to be accountable to.’ And the best kind of accountability is not some distant bureaucracy giving a test, but just feeling that you’re sharing a responsibility and working together. It’s a team kind of accountability at the local level.

;)